Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation (11 page)

Read Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation Online

Authors: Sean Bodmer

Tags: #General, #security, #Computers

Exploits and Vulnerabilities

Threats can range from simple opportunistic malware infection campaigns to highly advanced targeted malicious code that isn’t detected by host- or network-based security tools. Consider the sheer volume of vulnerabilities that are discovered in all sorts of computing platforms.

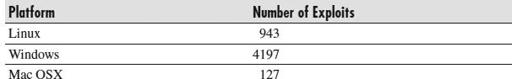

Table 1

shows some figures for 2010’s exploits borrowed from the Exploit Database (

http://www.exploit-db.com

). Although these figures include exploits that date back as far as 2003, they still reflect the volume of exploits that occurred. These exploits are operating system-specific and are not counted as third-party applications or services (such as PHP or SQL).

Table 1

Operating System-Specific Exploits

These exploits used both publicly disclosed and nonpublicly disclosed vulnerabilities. Now think about all of the exploit code developed for these discovered vulnerabilities. Then add all of the automated tools and crimeware that, once combined with the exploits, can be easily turned into an advanced persistent threat. Finally, consider how widely all of these platforms are connected and interacting across your enterprise network—whether in an enclosed network or in an enterprise that relies on cloud computing services.

You need to understand that for every vulnerability disclosed, not everyone has an exploit released publicly, but most have had some level of development on a private or classified level. Stuxnet is a great example—old and new vulnerabilities that never had exploits developed for them in the wild, yet there they appeared when the story broke.

The massively high volume of threat combinations floating around—based on statistical probability alone—is enough to make you want a little something extra in your coffee before work in the morning.

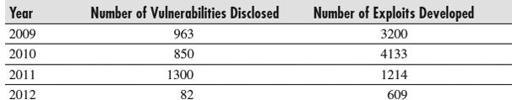

Table 2

shows the public vulnerabilities disclosed between 2009 and the first quarter of 2011 according to the National Vulnerability Database and the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT). These exploits were counted via the Exploit Database, where you can find most publicly available exploits. And keep in mind that for every ten publicly available exploits, there may be one sitting in someone’s possession waiting to be sold on the underground market to the highest bidder.

Table 2

Vulnerabilities Disclosed vs. Exploits Developed

As you can see, the public disclosure of exploits overshadows by far the public disclosure of vulnerabilities. Now let’s talk about some trains of thought to accompany that special cup o’joe.

Fighting Threats

You are more than likely interested in how to take the observable information a threat leaves in its wake and use it against the threat.

Observables

are logical fingerprints or noticeable specifics of an attacker’s behaviors and patterns that are collected and logged by various sensors, which are network and security devices across your enterprise that enable you to re-create the events that occurred. Observables are discussed in detail in

Chapter 3

of this book. For now, you just need to understand that observables are various components of data that, put together, can support attribution of a specific threat or adversary. If this information is handled, analyzed, and used properly, it can be used against your threat. The results will almost always vary in degree based on a few factors: the skill and resources of your attacker, your ability to identify and analyze each threat, and what degree of effort you put into operating against the most critical threats.

Identifying the best Course of Action (COA—numerous acronyms in this book have military etymology) for each threat will be a challenge, as no two threats are exactly alike. Some threats can be working toward nefarious goals, such as severe impact, physical damage, or loss of life goals (enterprise disruption, intellectual property damage, and so on). In our world of networked knowledge, billions of individuals around the world interact with systems and devices every day. And all these systems contain, at some level, information about that individual, group, company, organization, or agency’s past, present, and plans for the future. This information is valued in different way by different criminal groups.

Sean Arries, a subject matter expert on penetration testing and exploit analysis, once said, “If it is a monetary-based threat, the source is generally Eastern Europe. If it’s an information/intelligence-based threat, the source is generally based out of Asia. If it comes from the Americas, it could be either.” Based on historical information and analysis performed by the United States Secret Service and Verizon in their

2010 Data Breach Investigations Report

, there is a consensus that most monetary-based crimes come out of impoverished countries in Eastern Europe. As far as Sean’s quote goes, we completely concur, except the government employees who cannot confirm nor deny the events, with his expertise based on our own professional experiences.

Data and identities such as names, addresses, financial information, and corporate secrets can be bought and sold on the underground black market for all sorts of illegal purposes. Over the past few decades, the ability to detect identity theft has improved, but identify theft still happens today, as it did a century ago. Why? When an identity is stolen, there is a period of time in which the identity can be used for malicious purposes. This is generally until the victim of the identity theft discovers the information has been stolen and is being used, or the victim’s employer finds out credentials have been stolen (which can be a matter of hours to weeks). Thieves may use stolen identities to purchase items illegally, as a means to travel illegally, or to pose as that individual. Even worse, they might be able to gain access to sensitive or protected knowledge using someone’s stolen credentials. There is a broad spectrum of networked knowledge that may be targeted, ranging from personal financial information to government secrets.

All About Knowledge

Networked knowledge

is a term coined by retired US Army Colonel Hunt, one of the brainchildren behind the concept of NetForce Maneuver, a Department of Defense (DoD) Information Operations strategy that discusses tools and tactics that can be used against an active threat operating within your network. Colonel Hunt was also an early commanding officer of Sean Bodmer, who architected the DoD’s honeygrid (an advanced globally distributed honeynet that is undetectable and evolves with attackers’ movements). Networked knowledge is the premise of a combined knowledge of multiple organizations across their enterprises working together to share data about specific adversaries/attackers to gain attribution of specific operators and their motives and objectives.

For the purposes of this book, we emphasize the importance of a combination of knowledge and experience to better understand your attackers/adversaries and their objectives and motives. Knowledge is both your most powerful weapon and your enemy at the same time, as some of your knowledge (such as logs, records, and files) can be altered and lead you astray.

You know what you know, but when it comes to working across an enterprise or from home, there are unpredictable variables (proverbial monkey wrenches) thrown into the mix, such as the following:

The knowledge levels (expertise) of the developers behind the scenes, who all have varying levels of experiences and nuances of their own when they develop software; some of their levels of experience (or lack thereof) can be reflected in their coding

The knowledge levels of personnel responsible for providing your service

The knowledge levels of other users, friends, family, and peers