Richard The Chird

Authors: Paul Murray Kendall

COPYRIGHT © 1955, 1956 BY PAUL MURRAY KENDALL

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 56-10090

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FOR THE PUBLISHERS BY THE VAIL-BALLOU PRESS

TO

My two Carols

H

"3 «

•s

dfi

-«.s

rf

rl

_*l__:

J

°*

.."it

"T1

5 "»

•11

a

41

Contents

PREFACE PROLOGUE

BOOK ONE The King's Brother Part One Richard, Duke of Gloucester

4*

49 60

81

89

107

122

*33 142

150 162

181 193 207 218 239

VI. THE ROAD TO THE THRONE 255

VII. THE CHOICE 267

Part T

i. ENGLAND: 1483 277

II. THE KING'S PROGRESS 299

III. CONSPIRACY 312

IV. THE GREAT REBELLION 323 V. SPRING 334

VI. SUMMER 351

VII. CHRISTMAS 365

VIII. MAN AND GOVERNOR 370

IX. CASTLE OF HIS CARE 392

X. INVASION 410

XI. BOS WORTH FIELD 428

EPILOGUE 44J

APPENDIX I. WHO MURDERED THE PRINCES? 465

APPENDIX ii. RICHARD'S REPUTATION 496

NOTES 5^

BIBLIOGRAPHY 580 INDEX

Between pages 304 and 305

Richard III

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV

Middleham Castle from the South

The Battle of Barnet

Henry VI

Tewkesbury Abbey

Margaret of York

Antoine, Bastard of Burgundy

Parchment with signatures "EDWARDUS QUINTUS" etc,

The Hall of Crosby's Place, Richard's town house in Chelsea

The Tower of London

York Minster

Lady Margaret Beaufort, Mother of Henry VII

Thomas, Lord Stanley

Henry VII

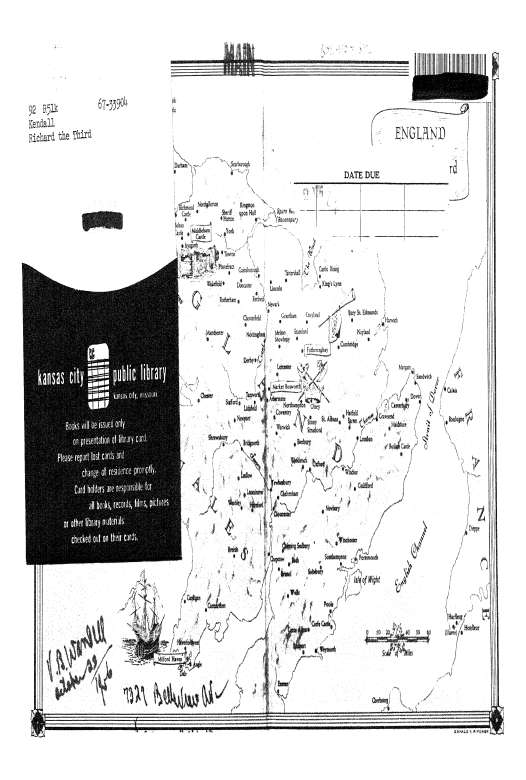

MAPS

England endpapers

Battle of Barnet I0 g

Battle of Tewkesbury no

Eve of Bosworth 438

Battle of Bosworth 430

GENEALOGICAL TREE

Lancaster and York <$

9

Preface

RICHARD the Third is perhaps the most polemical figure in the reaches of English history. Ever since the Tudor historians of the sixteenth century developed their picture of an archvillain, he has been the subject of bitter argument by those attacking or defending this view of him, which Shakespeare epitomizes in his popular tragedy Richard the Third.

In the course of this long controversy, Richard's career has usually been approached as stuff from which to create a "case," and his character has been treated as a cardboard counter, black or white, to be pushed back and forth in the struggles of the Great Debate. Is he a villain or is he not? Did he murder the Princes or did he not? Does the Tudor tradition present an accurate likeness, or is it a base slander? The books written about Richard have been largely devoted to arguing the answers to these questions.

The heats of argument are inimical to the art of biography. In this sense, it can be said that no life of Richard has ever been written. The object of this volume is to attempt such a life. I have sought to portray what manner of man Richard was, what manner of life he led, and something of the times of which he was a part. Moral judgments I have left as far as possible to the reader.

I have ignored the Tudor tradition, except in so far as it appears to offer bits of reliable evidence*, and I have based this biography almost entirely upon source material contemporary with Richard's day.

Since Richard is so controversial a figure, I have provided in the notes an opportunity for the reader to criticize the conclusions which I have drawn from conflicting or ambiguous testimony. Numbers which are starred refer to notes in which

evidence is discussed or additional information is supplied; the other numbers refer simply to sources.

I have tried to indicate clearly, either in the text or in the notes, what is fact and what is my own conjecture; and for conjectures of any importance I have given the reasons or evidence on which they are based. If the events of Richard's life and the general shape of his character had been previously established, I would probably have given freer rein to speculation. As it is, I have sought to hew him out of the facts, or as close an approach to the facts as I could make.

Nevertheless, a biography is a work of interpretation. A succession of facts does not create a life or reveal a character. The accuracy of my portrait of Richard depends, in the last analysis, on the validity of the imaginative judgments that I have drawn from the facts. The notes offer the reader some opportunity of estimating that validity for himself.

To deal with the central mystery of Richard's life—Who murdered the "Little Princes in the Tower"?—requires an analysis of evidence that is deadly to biography. I have therefore transferred my discussion of this enigma to an appendix (Appendix I). I have also provided, in Appendix II, a brief survey of the vicissitudes which Richard's reputation has encountered since he fell at Bosworth Field.

I owe an especial debt of gratitude to Alec R. Myers, Lecturer in Medieval History in the University of Liverpool, for reading my manuscript and offering suggestions and emendations of the greatest value; I have been able to indicate in the notes only a few of his contributions, and I can by no means indicate my appreciation of his labors and his encouragement.

I am likewise indebted to J. G. Edwards, Director of the Institute of Historical Research; C. H. Williams, of King's College, the University of London; Jack Simmons, the University of Leicester; K. B. McFarlane and C, A. J. Armstrong, of Oxford University; Denys Hay, the University of Edinburgh; and Col. A. H. Burne. I am grateful for the courtesy and help extended to me by the staffs of the London Library; the Students' Room, Dept. of MSS., and the Reading Room of the British

Museum; the University of London Library; the Public Record Office; and the Ohio University Library, particularly Miss Catherine Nelson.

For friendly assistance of many kinds I can make only inadequate acknowledgment to Richard Hough; Edward Hodnett, Ohio University; Charles Allen Smart; Edward H. Davidson, the University of Illinois; and Paul Murphy, Ohio University.

My research in England was accomplished during my tenure of a fellowship granted by The Fund for the Advancement of Education. The Research Fund, Ohio University, provided aid in the preparation of the typescript.

P. M. K.

Prolo

ue

What stratagems, ho

WHEN Harry the Fifth descended into the grave in August of 1422, he left a kingdom which seemed to be among the greatest and most fortunate of the earth. The rich provinces of France north of the Loire were in the hands of the Englivsh or their Burgundian allies; in the southwest, England had long held Guienne, a broad territory fanning out from Bordeaux. At home King Harry had restored the power of the Crown, employing the restless energies of the magnates in the sieges of French towns and stuffing gentry and commons with the spoils of victory.

Yet the moment he was dead, this empire began to disintegrate. He had exhausted the credit and the powers of his kingdom. He had taught his lords the habit of war as a way to wealth. He left behind him only a nine-month-old infant, in whose blood ran the madness of Charles the Sixth of France, father of the Princess Katherine whom Harry had married at the height of his success in 1420.

The dead king's cultured and unruly brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and his ambitious uncle, Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester and Cardinal, fell into a bitter contest for the supreme authority during the long minority reign. The council of regency split into quarreling factions; the retainers of the Duke and of the Cardinal fought in the streets of London; the magnates discovered, to their delight, that they could bicker as they pleased, help themselves to the royal revenue, and manipu-

*The scar indicates a noce in which evidence is discussed or additional information is supplied* An unstarred number indicates a note simply naming sources. Notes begin on p. 515.

*5

late the machinery of justice in their own interests. Meanwhile, John, Duke of Bedford, Regent of France, sought first to extend, then to maintain, and finally to salvage what he could of his dead brother's conquests. In the spring of 1429 the trumpets of the Maid sounded the beginning of the end. After three months of victories she led the Dauphin to Rheims and stood by the altar in white armor while he was crowned Charles the Seventh. She had so stirred the superstitious fears of Englishmen that the council had a desperate struggle to find even meager reinforcements for Bedford. Two years later, the Maid's agony at the stake in the market place of Rouen was probably witnessed by King Henry the Sixth himself, a frail and pious little boy of ten. But Joan's work was done. In February of 1435, Bedford was forced to retire from Paris. That summer the Duke of Burgundy at last heeded the voice of the peasant girl whom he had sold to the English. He agreed to forget that his father had been murdered by the courtiers of Charles the Seventh, and counseling his English allies to make peace, he returned to his allegiance as a Peer of France. Without the help of Burgundy the English cause was hopeless.

Twenty years after the death of Henry the Fifth, England still kept a precarious hold upon Guienne, Normandy, Maine, and bits of the lie de France. The chief towns of those provinces were islands beleaguered by a hostile ocean. The French nobles had withdrawn to the territories of Charles the Seventh; the starving peasants hated the English and cut their throats when they could; mercenary bands—the dreaded ficorcheurs —took service on either side or ravaged the country on their own. The English dared travel the roads only in armed bodies.

At home, the magnates fought among themselves as they pleased while the court staggered toward bankruptcy and trade was well-nigh paralyzed. The feud between Humphrey of Gloucester and the Cardinal continued its wasting course, but the two leaders were yielding to younger men. Cardinal Beaufort, overtaken by agt, went into partial retirement. His party was nbw headed by William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, an ambitious nobleman of princely tastes and rapacious habits. Hum-

phrey, though disgraced by the condemnation of his wife as a dabbler in witchcraft, was supported by Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, the greatest lord in the realm.

On the famous morning of Agincourt, October 25, 1415, Richard Plantagenet was a landless four-year-old orphan. His father, the feckless Earl of Cambridge, younger son of Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, had been attainted and executed on the eve of Henry the Fifth's departure for France, charged with plotting the overthrow of the House of Lancaster. The battle altered the boy's fortunes as much as England's. His father's childless older brother, Edward, Duke of York, fell in the thick of the fighting. The landless orphan was suddenly Richard, Duke of York, a royal ward of immense importance. His wardship was granted to Ralph Neville, first Earl of Westmorland. At Raby Castle in Durham, surrounded by the huge family of the Earl— his second wife had borne him thirteen children to supplement the ten given him by his first—Richard passed his boyhood and adolescence. Shortly before he left this household to assume his station in the kingdom, he was betrothed to the Earl's youngest daughter, Cicely, a high-spirited and beautiful girl who was romantically known as "the Rose of Raby." In 1430, at the age of nineteen, Richard accompanied his boy sovereign Henry to France and witnessed the empty mummery of his crowning in Notre Dame. Two years later he entered upon his inheritance, the richest in the realm. To the great holding of the dukedom of York were added not only his father's entailed lands but the vast Mortimer estates which came to him frojn his mother, Anne Mortimer, whose brother Edmund had died/childless in 1425.

For the next fourteen years of his life Richard enacted the roles which his rank and the times demanded: lord of his estates, councilor to the King, warrior and governor in the shrinking cmpery of France, In 1438, when he was twenty-seven and she a few years younger, he wedded the Rose of Raby—a puzzlingly late marriage for those days. They were rarely afterward parted. Neither continual pregnancy, the hardships of travel, nor the hazard of dwelling in English France or the Irish Pale deterred Cicely from accompanying her lord. Of the seven children who

lived, three were born at Fotheringhay (Anne, Margaret, and Richard), three at Rouen while their father was King's Lieutenant in France (Edward, Edmund, and Elizabeth), and George— from the beginning, a law unto himself—first saw the light of day in Dublin. In their beauty and their quickness of spirit these children resembled their mother. Richard, their father, appears to have been a quiet, solid man whose abilities were moderate but exercised with energy. He was a little below medium height, inclined to stockiness, with a square, forthright countenance which was attractive but not handsome. In France he ruled without brilliance, but firmly. In Ireland his fair dealing was to convert that troubled land into a bulwark of the House of York. Excessive greed and ambition—the besetting sins of his contemporary peers—seem to have been largely absent from his character. It would require the unrelenting enmity of a queen to remind him that he owned a better title to the throne than Henry the Sixth.

While York struggled in the early 1440'$ to govern France— without enough money, enough supplies, enough troops—the party of Suffolk and the Cardinal, which ruled the King, were turning to a policy of peace. In 1440 Charles d'Orleans, a friend of Suffolk's and a prisoner in England since the battle of Agin-court, was released to use his good offices for that purpose. Negotiations dragged on until 1444, when Suffolk and Adam de Moleynes, Bishop of Chichester, went to France to arrange a marriage for King Henry which would bring an end to the war,