Riding Barranca (11 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

Popi was appreciative of everything I didâthe posters I bought to hang on the hospital walls, the egg carton foam pad I got for the bed, the new scrapbook for his get-well cards. It was filling up quickly. I ordered a hospital bed for my parents' apartment, then went out and bought food to stock their kitchen, ordered vitamins, which he would never take, antioxidant tea, which he would never drink, and shark fin powder, which he would return. But mainly, what I did was distract him.

I wanted to do all I could, as if my efforts might make a difference in the final outcome. I wanted to get things set up before my mother came home. I dreaded that changing of the guard, for as much as she said she appreciated what I was doing, I knew underneath that she would be angry at me for doing what she could not.

Finally, the conscience-buzzer went off in her brain, and she realized that maybe she should be in Milwaukee taking care of her critically ill husband. She was suddenly concerned about the cancer that had been detected in his lymph nodes and insisted that he could not get chemo. “Everyone who gets chemo dies.”

My weepiness seemed to be an expression of my helplessness. I found myself sitting at a stop sign, waiting for the light to change until I realizedâthis was not a light: I could go. I felt as if some part of my brain was displaced, that I could easily forget where I was, where I was going, who I was calling on the telephone. I felt oddly removed, absent from myself.

Then, I braced myself for my mother's return. I had changed her sheets and made her bed. The apartment was immaculate. But on entering the apartment, she started moving bouquets around as if each one had been set down in the wrong place.

She said how wonderful I had been to come and take care of her husband, but then, in the same breath, she went on to tell me how she had played golf on Tuesday and tennis on Wednesday. I was appalled.

“The doctors want Popi to come home on Friday,” I told her.

“He's not coming here until Monday when I'm ready for him,” she snapped. I guess she needed four days to unpack her things. Wanda was being flown all the way from Arizona to help her rearrange her closet.

The first day home, she had scheduled a hair appointment in Hartland, an hour away, and she wondered if I wanted to go along and have a massage. I declined.

On arriving at the hospital, one of my cousins was visiting with his kids. Mom came in like a fury ordering everyone to leave, insisting that children should not be allowed to visit. He could catch pneumonia. Yes, and he could catch a lot of things spending an extra four days in the hospital.

I could visibly see my father's spirits drop. He was upset by her outburst. He was not strong enough to take it. He told her she should not come to the hospital if she was going to bring so much tension with her. She stayed fifteen minutes, then left. “This is all too much for me.”

I suggested that it might be fun to share Chinese takeout with Popi at the hospital that evening, but she wanted to treat me to some new, fancy restaurant, and I felt obliged to go. Once we had settled into our leather booth, she recounted how my niece, Daphne, had gotten so upset about Popi that she started crying at school, unable to finish her exam. Hearing this, I started to cry as well. Mom was horrified. “For heaven's sake, don't cry here in the restaurant!”

I wanted to discuss what the doctors had said and her only response was, “I don't want to talk about him. I'm sick of talking about him.”

Everything she said rubbed me wrongâhow he could have NO visitors. No phone calls either. Even though the doctors wanted him up, leading a normal life, moving, exercising, getting his metabolism going, but she insisted, “I need some time to rest.” As far as she was concerned, he shouldn't have gotten cancer. He shouldn't have done this to her!

On my last day, I brought my father a St. Christopher's medal on a silver stirrup key chain and told him that he would have to take good care of himself. Perhaps, I had been too present, too over-organized, too much in her way, but I felt terrible about the situation as I got ready for departure. I could not see how this transition to home would work for him. I only wished that my sister was there, but she and her family were still in Africa.

When I talked to Mom on the phone from Massachusetts, her anger was palpable. “I wash my hands of him, the whole thing! He's just impossible. I'm not even speaking to him.”

One day, I tried for hours to get through, and it was obvious that she had taken the phone off the hook. I wanted to get a release for my father's pathology reports, to have them sent to another doctor who had had success with alternative medicine. When I finally got through around dinnertime, I said to Mom, “You can't just take the phone off the hook for six straight hours. The doctors couldn't even get through.”

“Do you have anything more you want to say?” she snarled. “Do you want to speak to your father?” Then, I could hear her yell in the background. “She thinks you are her husband!”

A half-hour later, my mother called Mason crying hysterically and saying that I was such a troublemaker I had ruined their evening, and that I should never call their house again.

Breeze

Daphne longs to see the valley, so we decide on a short morning ride, before heading down to Nogales for lunch at

La Roca.

She tries out Tonka this morning, and I take Peanut, who has had several days of rest since coming back from Melinda's. I am eager to see how he will do on the trail now, and he goes beautifully.

It is pleasing to see Daphne's dark silhouette on the top of a rise with all that space surrounding her. She is having a bit of trouble keeping Tonka in his gaited walk as he continually breaks into a canter. She is probably sitting too far forward, and I tell her to let her feet drop from the stirrups as if she were barebackâ“That's how you're supposed to sit.” At some point, after riding a gaited horse, it just clicks in. One has

to listen for the sound of the hooves on the hard-packed road, sounding like “a

piece of meat a shucked potato, a piece of meat a shucked potato⦔

When we do want to go faster, Peanut shows me a lovely little lope that is extremely comfortable. I keep giving him lots of praise as we ride out over the open valley. Leaving the dirt road, we cross the grasslands, toward the headwaters of the Santa Cruz, now filled with waterâit is good to see this place transformed back to wetlands from the muddy hole it had been just a month ago.

On the drive home, I take it easy. I have heard that every bump in the road is magnified in the trailer, and that one should drive as if carrying a full tray of champagne flutes. We pass the Hale Ranch where two cowboys are mounting mules. Daphne says how she likes to ride mules when she is at their ranch in Montana, because they are so surefooted and not scared by bears.

One time, when she was only twelve years old, riding out West near Yellowstone National Park at a friend's family place, she went out with five others, up high in the mountains. They were all just standing in a circle when they spottedâ

“A bear!”

The other horses all dumped their riders, and some of the people were trampled, but Daphne stayed on. She put herself between the fallen riders and the bear and stared the huge grizzly down until it lumbered off.

Because she was the only one still on her mount, they told her to head back to the ranch to get help. It had taken them hours to get to that point, but she galloped off and came into the ranch house panting. A fancy party was in progress with a lot of New York City and Virginia guests. When she announced that there had been a bear, no one believed her.

They thought she was pulling a prankâat which point, she burst into tears. Only then did they listen to her and send out a helicopter to pick up the injured.

Ready to Ride

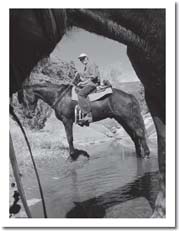

Helen and I descend to Sonoita Creek, but once we are down, I suggest that we take a right-hand turn on the Cottonwood Loop Trail, which is supposed to be for hikers only, no horses. Helen is game. The two of us have always been apt to break the rules. In any case, we wonder why horses are banned from this trail as there aren't any low-hanging branches. It seems perfectly fine. Perhaps it is a bit wilder here, with a lot of bird lifeâducks lifting off from the stream in pairs.

At the far end of the loop, we take another forbidden path up the Blackhawk Trail, until we see a ranger's white truck across the creek, and decide to leave the path and wander upstream through flowing water. Barranca picks his way over the submerged stones. As we proceed up the gradual incline

of the river, we turn a corner, and see white water and a forty foot waterfall at the end of the canyon. We are both giddy with excitement.

Riding back up to the edge of the bluff, the footing is precarious, but the horses are only disturbed by one tall barrel cactus that is lying down on its side, rather than standing upright. Helen says one horse she knew was frightened by a felled Christmas tree. Somehow horses know how things are supposed to stand, and their instincts for survival always keep them on the alert, ready to balk or flee. The other day Peanut didn't like the looks of a big brown boulder. Did he think it was a predator or someone in a crouched position?

Passing through the arid desert pasture we come over a rise and are at the same level as Patagonia Lake. There is something so surprising in this that we liken it to the feeling of awe one has driving over the rim of the San Rafael Valley, seeing the abundant grasslands spreading out beyond.

At the level of the spillway, where the water flows from the lake down to the cascading falls and into the creek below, Barranca resists crossing the cement area covered with shallow water, though he has just gracefully picked his way across slippery river rocks and forded deeper water. He must sense that the wet cement could be treacherous.

We decide to go back down into the leafy green comfort of the riverbed, taking the other side of the Cottonwood Loop Trail until it disappears into the unmarked woods. Bushwhacking through the forest on the western side of the river, we make our way back through groves of large mesquite trees, rummaging around. We are not quite sure where we are, but it doesn't seem to matter, other thanâ

we are not supposed to be here.

Finally, we find our way back to the trail and then settle down for lunch. I share my sandwich and chocolate with

Helen, as she has not packed anything today. The Saga blue cheese and chicken sandwich with a layer of sun-dried tomato paste is enough to fill us both, and the horses munch. Golden poppies have begun to flower all about their hooves.

Helen on Ben

I am supposed to meet Helen at her corral at ten in the morning, but at nine-thirty she calls to tell me that Mike is out looking for the horses on their forty-acre spread. After breakfast, Pinto Bean wormed his way out of the corral, followed by Bendajo. The mare, Copper, was so aggravated, she jumped into the huge water trough and out again on the other side to join the geldings. Mike is now trying to round up the horses with his four-wheeler. I suggest that she call me when the horses return.