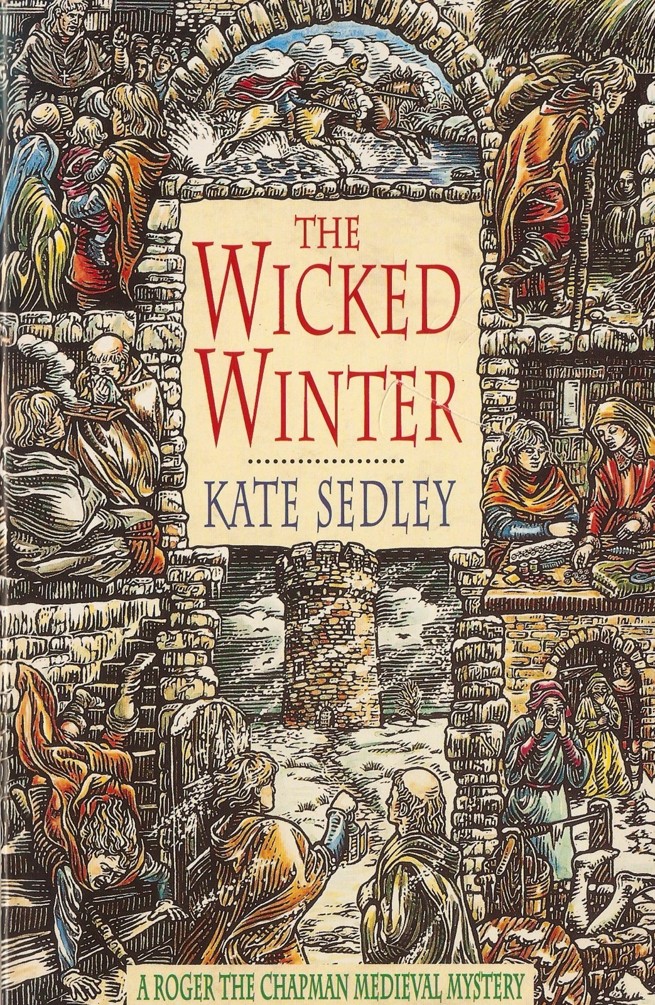

[Roger the Chapman 06] - The Wicked Winter

Read [Roger the Chapman 06] - The Wicked Winter Online

Authors: Kate Sedley

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Historical

Kate Sedley was born in Bristol and educated at The Red Maids' School, Westbury-on-Trym. She is married, has a son and daughter, and one granddaughter. THE HANGED MAN is her third detective novel and follows DEATH AND THE CHAPMAN and THE PLYMOUTH CLOAK ('compares well to Ellis Peters' Brother Cadfael tales' Publishers Weekly).

Also by Kate Sedley

Death and the Chapman

The Plymouth Cloak

The Hanged Man

The Holy Innocents

The Eve of St. Hyacinth

The Wicked Winter

Kate Sedley

Copyright © 1996 Kate Sedley

The right of Kate Sedley to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 1993 by HEADLINE BOOK PUBLISHING

First published in paperback in 1997 by HEADLINE BOOK PUBLISHING

10987654321

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

ISBN 0 7472 5631 4

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berks

HEADLINE BOOK PUBLISHING A division of Hodder Headline PLC 338 Euston Road London NW13BH

The Wicked Winter

Chapter One

It was bitterly cold. In the last few minutes a wind had arisen, blustering across the house-tops from the river Frome, moaning between the houses and rattling all their shutters like the teeth in an old man's head. My mother-in-law, standing beside me, reached across and pulled the woollen shawl closer about my sleeping daughter who weighed so uncomfortably against my shoulder. Elizabeth, now two months past her first birthday, as well as inheriting my fair hair and blue eyes also promised to have my height and build, and she was a heavy child for her age. I shifted her sleeping form as gently as I could from my right arm to my left, but even that, like the powerful voice of the friar who preached from the High Cross, failed to awaken her. But it disturbed several other members of the tightly packed congregation, who turned frowning faces towards me and bade me be still.

The reputation of the Dominican friar, Father Simeon, had preceded his appearance in Bristol by many months. It had already been one of the main topics of the marketplace when I returned to Margaret Walker's home, amongst the weavers and spinners of the city, the previous September.

Now at last, in the first week of an icy January of the year of Our Lord 1476, the great preacher had finally arrived; and on this Monday morning, braving the treacherous conditions underfoot, the citizens had left their work and flocked to hear what he had to say.

Reluctant to quit the fireside, I had offered to remain at home with Elizabeth while my mother-in-law went alone, but Margaret would not permit it.

'It will do you good,' she had retorted, 'to listen to a rousing sermon for a change. The Word of God is too little expounded in the churches nowadays. Not,' she added hastily, 'that I am accusing the parish priests of failing in their duty. Heaven's my witness that I meant nothing of the kind! It's just that the poor men are too overburdened with the rigours of office to find time to explain the Scriptures. They're content to leave that to the friars.'

'Oh?' I questioned the truth of this judgement. 'I thought the Church accused all the Orders of avarice, lechery and hypocrisy. You know the saying: "Friars and fiends be but little asunder."'

Margaret looked displeased. 'I pay no heed to common gossip and neither should you. It ruins the reputations of too many good people.'

I knew she had cause for her dislike of unfounded calumnies and gently squeezed her hand.

'Mother,' I said, although the title had always been inclined to stick in my throat, 'it's not just that I want to sit in the warm for a little longer on such an unpleasant morning, but surely it's unwise to expose Elizabeth to the bitter weather.'

She laughed mirthlessly. 'And what, pray, would you know about what is and what isn't wise for the child? She's over a year old, and these past four months have been the longest time you've spent in her company since she was born. And you'll soon be off on your travels again. Oh, don't deny it! I recognise the signs. You've been restless for days now, peddling your wares from dawn to dusk. And since Christmas, as the days lengthen, you've ventured a little further afield each time. On at least three occasions you've travelled so far that you've been unable to return home at night.'

'I'm a chapman,' I protested. 'I have to go abroad to sell my wares.' But I could hear the note of guilt in my voice.

Margaret heard it too, and smiled acidly. 'There are enough villages and homesteads in the neighbourhood to keep you busy; and with ships from foreign parts constantly dropping anchor along the Backs, no shortage of supplies to replenish your pack. With the money I earn from spinning we don't lack for food or clothing, nor for a roof over our heads. We could settle down here very comfortably together until you decide to marry again - as a big, strong, handsome lad like you is bound to do one day. I'm quite prepared for that. But there are plenty of local girls who'd be more than willing to have you, and Alderman Weaver, after what you did for him, would doubtless let you have one of his cottages to live in.

You wouldn't be far away and I could still visit Elizabeth whenever I wished.'

'I see you've been making plans for me,' I answered, trying to make light of my resentment.

Margaret gave an emphatic shake of her head. 'No, Roger lad, I shouldn't dare. I know they're only daydreams. You have the wanderlust in you. I accepted that fact very early on in our acquaintance. It was the reason you couldn't take your final vows and become a monk. It's why, in a way, I'm glad that Lillis didn't live beyond that first autumn of your marriage. She couldn't have borne all the partings, never knowing when she was going to see you again.'

'Forgive me,' I begged, once more pressing her work-roughened hand. 'I know it must be lonely for you, bringing up Elizabeth on your own.'

'We are as God made us,' she replied philosophically. 'We must do His will as we think fit. You were born a rover and you won't change yet awhile. However,' she added in a brisker tone, 'you aren't wriggling out of coming with me this morning to hear Friar Simeon preach. Elizabeth will do well enough if she's wrapped up properly, and you can carry her in your arms. It shouldn't be too difficult for someone as strapping as you.'

But she overestimated even my strength, for as I have already said, my daughter was not a delicate child. (Today, in her thirty-eighth year, Elizabeth has more than fulfilled that early promise. She is a big, tall, handsome woman, not easily roused to anger, but ruling her husband and children, and above all me, with a fist of iron concealed in a silken glove.) My arms were aching long before the friar had reached the halfway point in his dissertation.

Simeon was a tall, cadaverous man with the thin, dyspeptic face of the true fanatic. His arms flailed the air as he spoke eloquently of hellfire and damnation, and his eyes glowed like coals in their sunken sockets. Too little food and too much penance had made him feverish. Hectic spots of colour burned in either cheek and there was a bluish tinge around his lips. His black Dominican habit was mired and dusty about the hem with much walking of the winter roads, and the sparse brown hair hung lankly to his narrow shoulders.

At the end of half an hour my mind began to wander, going back over the extraordinary events of the previous year (which I have set down in detail elsewhere, but which at that time I judged it wise to keep to myself). By the end of another half hour I was unable to think of anything except the extreme discomfort caused by Elizabeth's weight. There was no feeling in either of my arms and I was in serious danger of dropping her.

But help was at hand. Friar Simeon was obviously coming to the end of his sermon. The crowd was hushed now, tense and expectant, as a great wave of elation seemed to wash through the preacher's body. He reached up into the heavens as though he could bring down God to fight on his side.

Once again the impassioned tones rang out.

'Three things are necessary for the salvation of man! To know what he should believe, to know what he ought to desire, to know what he should do! Believe in God, desire God, serve God! Renounce the temptations of the flesh for they are the temptations of the devil! Prayer and purity, my children! These are the things we must strive after!' Men were swaying now in a kind of ecstasy; women were weeping uncontrollably. The crowd was aflame, kindled by the spark of the friar's emotion.

'So I bid you all go forth and root out evil wherever you may find it! Perfect blessedness is a vision of God!' There was a moment's profound silence, as if indeed we had all been vouchsafed that vision. Then with a sudden concerted movement his listeners began to disperse, drifting away like people awakening from a dream, back to their humdrum existence. For a while they had touched the heights, each one capable of a place among the saints. Now the real world intruded. Anger, envy and greed reared their ugly heads once more.

I heaved a sigh of relief at the conclusion of my ordeal just as my daughter stirred and opened her eyes, blinking placidly.

'Heigh-ho, lass!' I said and swung her on to my back, her little arms clasped trustingly around my neck. I turned to Margaret. 'Can you tuck the shawl around her?' But my mother-in-law had disappeared. Moments later I saw her stooping over the friar who had lowered himself to the ground, exhausted by his labours, his emaciated body hunched against a wintry blast of wind. She was smiling triumphantly, and I guessed correctly that she had beaten the two other local matrons who crowded at her heels in their bid to offer hospitality to the preacher. I sighed resignedly. I had hoped for a quiet dinner, during which I had intended to break it gently to Margaret that her suspicions, voiced earlier that morning, were well founded: I had to get away soon from the stifling domesticity of the cottage and travel the road for a while; not for long, only a sennight, or a fortnight at the most.

The need to go had become overwhelming. I had been fighting it for days, knowing from past experience that when the longing grew to be as powerful as this, God had work for me to do. Of course I argued with Him about it. I always did, although I knew that any priest would tell me that it is wrong to address oneself directly to the Almighty. He is too awesome, too clouded in glory, to be approached by lowly sinners. The multitude of saints, the Virgin Herself, are there to intercede on our behalf, to take upon their own shoulders the trivial burdens of our days. But I had always secretly rebelled against this notion. Throughout life I have found it better to speak directly, wherever possible, to the head man.

God, as usual, listened patiently to everything I had to say and then proceeded with His own plans as if I hadn't spoken. Naturally I'd known what the outcome would be, but protesting gives me a sense of independence and the prospect that one day I might even win.

Margaret retumed, the friar walking beside her.

'Roger, Brother Simeon has done us the honour of agreeing to share our dinner. Brother, this is my son-by-marriage, Roger the chapman.'