Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric (Key Conflicts of Classical Antiquity) (11 page)

Authors: Michael Kulikowski

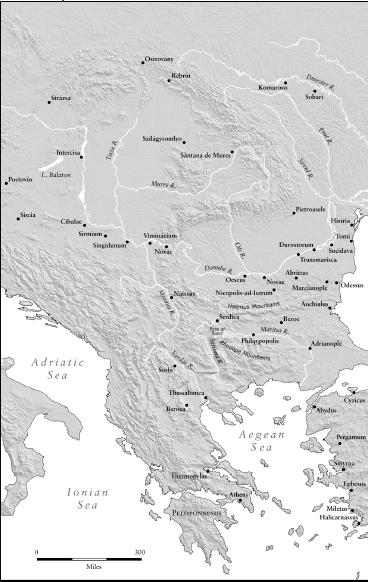

In the course of the 290s, Diocletian transformed the Roman empire beyond recognition. A governmental revolution grew out of the emergency measures which Diocletian undertook piecemeal in order to keep himself secure on his throne. The cumulative effect of such measures was enormous. It removed many of the systemic causes of disorder that had plagued the third-century empire, and thereby created the powerful Roman state with which the fourth-century Goths had to deal. As we have seen, the first important step that Diocletian took was to appoint

Maximian as his fellow augustus, or co-emperor, in 285. The point of this measure was to multiply the imperial ability to deal with many different threats at one time. An emperor who was on the spot and seen to be doing his job was a powerful disincentive to usurpation by a local governor or general. Diocletian took this principle still further, by appointing

two junior emperors, called caesars, as a complement to the two senior augusti. Together, these four emperors would form an imperial college in which the actions of each emperor would symbolically be the actions of all four: a law issued by one emperor was issued in the name of all four, and when one emperor won a victory, all four took

the victory title associated with it. This college of four emperors is known to scholars as the tetrarchy (‘rule of four’ in Greek). For as long as it lasted, the new tetrarchy of Diocletian and Maximian, with

their caesars

Constantius and

Galerius, ensured that an emperor was on hand in nearly every trouble spot of the empire, ready to suppress a looming threat and thereby discourage any local response that might challenge the hold of Diocletian and his colleagues on their thrones. The tetrarchic system was also meant to ensure a smooth succession, as a caesar would be waiting to succeed a senior augustus should the need arise.

Diocletian’s reform of the imperial office was accompanied by an

elaborate religious ideology that assigned to the ruling emperors divine descent from Jupiter and Hercules, those gods that were most ostentatiously Roman in the traditional pantheon. The tetrarchy also insisted on renewed attention to the imperial cult – the worship of past, deified emperors and of the genius, or protecting spirit, of the living emperor. Both measures were designed to ensure that the gods would smile on and protect the empire. The famous Diocletianic persecution of Christians, widely known as ‘the Great Persecution’, was a consequence of this tetrarchic ideology, because Christians refused to worship any god but their own and by doing so might endanger the health of the state

. If religion was one basis on which Diocletian rested his authority, he took other measures as well, reforming the currency, expanding the army, and re-enforcing the elite guard units that traveled with the emperor. Most importantly, he broke up the very large provinces of the early empire into more than a hundred smaller provinces, while also separating the military and civilian hierarchies in the imperial government. The first measure dramatically reduced the scale of any one official’s command, while the second meant that the officials who collected taxes and disbursed state salaries to the soldiers were not the same officials who commanded the troops in the field. Together, both measures undermined the ability of either military or civilian officials to claim the imperial throne for themselves. As we have said, the various Diocletianic reforms were

ad hoc

measures, meant to deal with the many different problems that had afflicted the third-century empire. Yet as a group, they were revolutionary: they not only allowed Diocletian to hold his throne for more than two decades, they also produced a system of government that remained effective even after the tetrarchy itself broke down. In other

words, the type of imperial goverment originally outlined by Diocletian and the tetrarchy was in essence the same one with which Alaric had to deal a hundred years later. More important for our immediate purposes, however, Diocletian’s reforms meant that for the first time in over half a century, a Roman emperor was secure enough on his throne to deal effectively with barbarians beyond the northern frontier – with serious consequences for the Goths.

This new imperial strength meant that the constant stream of frontier wars slackened considerably in the years before 305, when the augusti Diocletian and Maximian abdicated and passed the senior title on to their caesars

Constantius and

Galerius, who then appointed two new caesars to serve as their junior emperors. Instead of constantly reacting to events beyond their control, the tetrarchs were increasingly able to decide when and where they wanted to fight along their frontiers. They began to co-opt powerful barbarian leaders into imperial circles, and to manage the affairs of their barbarian neighbours in what they perceived as the best interests of Roman power. This policy can be inferred from obscure, but clearly very important, disturbances along the lower Danube in the 290s and early 300s. We saw in chapter

one

how

Diocletian won a victory over one group of Goths, the

Tervingi, as the panegyric of 291 attests. We do not know what prompted the campaign that led to that victory, but the decade that followed seems to have witnessed the substantial growth of Tervingian power. Although this Gothic expansion is not attested by positive evidence, it can be inferred from other known events, most importantly the displacement of an older barbarian grouping. Sometime before early 307,

Galerius fought a campaign against the

Sarmatians, which is to say in the region between the Danube and the Tisza rivers. Then, in the summer of 307, he attacked the

Carpi further east, settling a very large number of them in a Roman province south of the Danube as defeated subjects of the empire.

[54]

The willingness of the Carpi – virtually all of them, it seems – to be removed from a territory in which they had dwelt for well over a century

is significant. It suggests that the military pressure of a neighbouring barbarian power had become too great for them to sustain and that their attempts to find refuge in the empire had provoked a punitive imperial campaign. The Gothic Tervingi are the barbarian group most likely to have affected the Carpi in this way

. We seem, in other words, to see an increasingly powerful Tervingian polity near the mouth of the Danube extending its power at the expense of its immediate neighbours, perhaps with the tacit support of the imperial government. That support can probably be inferred from the fact that the tetrarchs fought no campaigns against the Tervingi after 291. On the contrary,

Goths may have been recruited into the imperial army and served with

Galerius in Persia, though the only evidence comes from Jordanes and is therefore suspect.

[55]

It is thus quite likely that the tetrarchs were complicit in the build-up of Tervingian power, viewing them as a favoured barbarian group which could help keep in check other barbarians further up the course of the Danube.

There was a real logic to that approach. While the lower Danube was consistently under the firm control of an emperor resident in the Balkans (first Galerius, then Licinius), the provinces of the middle and upper Danube were the usual setting for confrontations between rivals in the years after 305. Because this imperial preoccupation with the upper and middle Danube lasted for a full two decades after 305, imperial support of Tervingian hegemony in this period is quite plausible. It would, moreover, allow us to make sense of

two massive ditch-and-rampart wall systems which were built around this time in Bessarabia and Galatz, well beyond the imperial frontiers. Like the long east-west wall system known as the

Csörsz-árok, built beyond the Pannonian frontier in modern-day Hungary, these fortifications are of a quality and on a scale that could not have been attained without imperial approval. From the imperial point of view, it would be useful to have a reliable Gothic ally keeping the lower Danube quiescent. By favouring the Tervingi, allowing fortifications to be built in their lands on such a scale, their strength and security could act as an additional layer of imperial defence, allowing emperors to focus on more immediate threats elsewhere

. Imperial support along these lines explains why the Tervingi

are so much more powerful when we next meet them in our sources, around the year 320.

In the meantime, however, the tetrarchic experiment had broken down entirely. Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in 305, for reasons that remain extremely controversial

. Galerius and

Constantius became augusti, but the choice of new caesars caused problems. Rather than the sons of Maximian and Constantius, who had long been groomed for the succession, two of Galerius’ close supporters were appointed as caesars. Before long, however, both the imperial children had seized the purple for themselves. After his father died at York in 306,

Constantine was acclaimed emperor, supposedly at the instigation of the Alamannic king

Crocus, a client of the late Constantius and an early example of a barbarian noble holding a high position in the imperial army.

[56]

Maxentius, the son of Maximian, was proclaimed emperor at Rome in the same year, with the support of the Roman populace. Constantine’s proclamation was soon recognized by the senior augustus Galerius, but Maxentius was never accepted as a legitimate emperor. For half a decade between 307 and 313 the Roman empire was wracked with civil wars that gradually eliminated most of the key claimants to the imperial title.

By 313, there were only two emperors left, Constantius’ son Constantine (r. 306–337), now a fervent Christian, in the West, and

Licinius (r. 308–324), an old comrade of Galerius, in the East. Despite their violence, the civil wars of 307–313 demonstrate the basic solidity of the Diocletianic reforms, because the hallmarks of the third-century crisis are entirely absent from the post-tetrarchic conflicts: no provincial general made an opportunistic bid for the throne, no provinces broke away under their own imperial succession, and no barbarian kings exploited the situation to launch a major invasion across the frontiers.

Indeed, a firm hand was kept on the imperial frontiers despite active civil war. Even before they had done away with other rivals, Constantine and Licinius between them controlled most of the Rhine-Danube frontier. Both undertook traditional imperial campaigns into the

barbaricum

, Constantine leading

Frankish kings in triumph at

Trier,

Licinius attacking Sarmatians near the

Danube bend.

[57]

As always, we cannot know precisely what prompted the individual campaigns, but the perpetual demand for imperial victories, combined with a need to control barbarian politics while preparing for internal Roman conflict, can explain most of the fighting. A similar calculation probably lies behind the momentous propaganda decision which Constantine took in 310. In the old tetrarchic ideology, Constantius had been the adoptive son of Maximian, and hence took on his adoptive father’s putative descent from the god Hercules, along with the name Herculius that represented it. In 310, however, Constantine repudiated the Herculian name which he had inherited from Constantius. He instead began to claim descent from the emperor

Claudius Gothicus, a fiction first attested on 25 July 310.

[58]

It made sense for Constantine to rid himself of the old Herculian connection after his final break with

Maximian and Maxentius in 310, but there may have been more to it than that. Claudius, one of the third century’s great military heroes, won his Gothic victories in the Balkans. Constantine’s claim to a Claudian descent may be the first indication of the Balkan ambitions he was to demonstrate before too long.