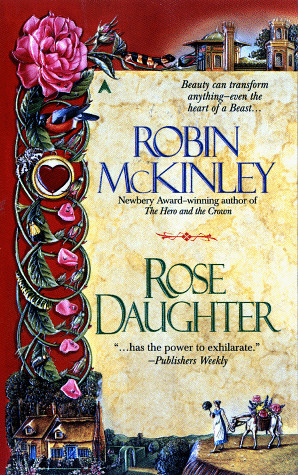

Rose Daughter

Authors: Robin McKinley

Robin McKinley

1997

ISBN: 0-441-00583-7

“Every sentence and every occurrence seems infused by magic.

I will keep this book. I will reread it, time and again; it has earned its

place as one of my odd coterie of bedside companions.”

—

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Books By Robin McKinley

Novels And Short Stones

Beauty: A Retelling Of The Story Of Beauty And The Beast

The Door In The Hedge

The Blue Sword

A Newbery Honor Book

The Hero And The Crown

Winner Of The Newbery Medal

Imaginary Lands

Edited By Robin McKinley

The Outlaws Of Sherwood

Deerskin

A Knot In The Grain And Other Stories

Picture Books

My Father Is In The Navy

To Neil and Tom,

whose absurd idea it was

and in memory of a

little lilac-covered cottage

where I used to live

Her

earliest memory was of waking from the dream. It

was also her only clear memory of her mother. Her mother was beautiful,

dashing, the toast of the town. Her youngest daughter remembered the blur of

activity, friends and hangers-on, soothsayers and staff, the bad-tempered pet

dragon on a leash—bad-tempered on account of the oca-mnda leaves in his food,

which prevented him from producing any more fire than might occasionally singe

his wary handler, out which also upset his digestion—the constant glamour and

motion which was her mother and her mother’s world. She remembered peeping out

at her mother from around various thresholds before various nurses and

governesses (hired by her dull merchant father) snatched her away. She remembered

too, although she was too young to put it into words, the excitability, no, the

restlessness of her mother’s manner, a restlessness of a too-acute alertness in

search of something that cannot be found. But such were the brightness and

ardour of her mother’s personality that those around her also were swept up

into her search, not knowing it was a search, happy merely to be a part of such

liveliness and gaiety.

The only thing that ever lingered was the sweet smell of her

mother’s perfume.

Her only memory of her mother’s face was from the night she

woke from the dream for the first time, crying in terror. In the dream she had

been walking—she could barely walk yet in her waking life—toddling down a long

dark corridor, only vaguely lit by a few candles set too far into their

sconces, too high up in the walls. The shadows stretched everywhere round her,

and that was terrible enough: and the silence was almost as dreadful as the darkness.

But what was even worse was that she knew a wicked monster waited for her at

the end of the corridor. It was the wickedest monster that had ever lived, and

it was waiting just for her, and she was all alone.

She was still young enough to be sleeping in a crib with

high barred sides; she remembered fastening her tiny fists round the wooden

bars, whose square edges cut into her soft palms. She remembered the dream—she

remembered crying—and she remembered her mother coming, and bending over her,

and picking her up, whispering gently in her ear, holding her against her

breast, softly stroking her back. Sitting down quietly on the nurse’s stool and

rocking her slowly till she fell asleep again.

She woke in her crib in the morning, just as usual. She

asked her nurse where her mamma was; her nurse stared and did not believe her

when she tried to tell her. in the few words she was old enough to use, that

her mamma had come to her in the night when she had cried. “I’d’ve heard you if

you yelled, miss,” said the nurse stiffly, “And I slept quiet last night.”

But she knew it was her mother, had to have been her mother.

She remembered the sweet smell of her perfume, and no one but her mother ever

wore that scent.

Her perfume smelt of flowers, but of no flowers the little

girl ever found, neither in the dozens of overflowing vases set in nearly every

room of their tall, magnificent town house nearly every day of the year, nor

anywhere in the long scrolling curves of the flower-beds in the gardens behind

the house, nor in the straight, meticulous rows within the glasshouses and

orangeries behind the garden.

She once confided to a new nurse her wish to find the flower

that had produced her mother’s scent. She was inspired to do so when the nurse

introduced herself by saying, “Hello, little one. Your daddy has told me your

name, but do you know mine? It’s Pansy, just like the flower. I bet you have

lots of pansies in your garden.”

“Yes, we do,” replied the little girl politely. “And they’re

my favourite—almost. My favourite is a flower I do not know. It is the flower

that my mother’s scent comes from. I keep hoping I will find it. Perhaps you

will help me.”

Pansy had laughed at her, but it was a friendly laugh. “What

a funny little thing you are,” she said. “Fancy at your age wanting to know

about perfume. You’ll be a heart-breaker in a few years, I guess.”

The little girl had looked at her new nurse solemnly but had

not troubled to explain further. She could tell Pansy meant to be kind. It was

true that she had first become interested in gardens as something other than

merely places her nurses sometimes took her. in the peremptory way of

grown-ups, when she had made the connexion between perfume smells and flower

smells. But she had very soon discovered that she simply liked gardens.

Her mother’s world—her mother’s house—was very exciting, but

it was also rather scary. She liked plants. They were quiet, and they stayed in

the same place, but they weren’t boring, like a lot of the things she was

supposed to be interested in were boring, such as dolls, which just lay there

unless you picked them up and did things with them (and then the chief thing

you were supposed to do with them, apparently, was to change their clothes, and

could there be anything more awfully, deadly boring than changing anyone’s

clothes any more often than one was utterly obliged to?). Plants got on with

making stems and leaves and flowers and fruit, whatever you did, and a lot of

them were nice to the touch: the slight attractive furriness of rabbit’s-ears

and Cupid’s darts, the slick waxy surfaces of camellia leaves and ivy—and lots

of them had beautiful flowers, which changed both shape and colour as they opened,

and some of them smelt interesting, even if none of them smelt like her

mother’s perfume. And then there were things like apples and grapes, which were

the best things in the world when you could break them off from the stem

yourself and eat them right there.

From the nurses’ point of view, the youngest girl was the

least trouble of the three. She neither went out seeking mischief, the more

perilous the better, the way the eldest did, nor answered impertinently (and

with a vocabulary alarmingly beyond her age), the way the second did. Her one

consistent misbehaviour, tiresome enough indeed as it was, and which no amount

of punishment seemed able to break her of. was that of escaping into the garden

the moment the nurse’s eye was diverted, where she would later be found,

digging little holes and planting things—discarded toys (especially dolls),

half-eaten biscuits, dead leaves, and dry twigs—singing to herself, and

covering her white pinafores and stockings with dirt. None of the nurses ever

noticed that the twigs, were they left where she planted them, against all

probability, grew. One old gardener noticed, and because he was old and

considered rather silly, he had the time to spend making the little girl’s

acquaintance.

Nurses never lasted long. Despite the care taken and the warnings

given to keep the nurses in the nurseries, eventually some accident of meeting

occurred with the merchant’s wife, and the latest nurse, immediately found to

be too slow or too dowdy or too easily bewildered to suit, was fired. When

Pansy came to say good-bye, she said, “1 have to go away. Don’t cry, lovey,

it’s just the way it is. But I wanted to tell you: it’s roses your mum’s

perfume smells of. Roses. No, you don’t have ‘em here. It’s generally only

sorcerers who can get ‘em lo grow much. The village I was born in, we had a

specially clever greenwitch, and she had one. just one, but it was heaven when

it bloomed. That’s how I know. But it takes barrels of petals to make perfume

enough to fill a bottle the size of your littlest fingertip—that’s why the

sorcerers are interested, see, I never knew a sorcerer wasn’t chiefly out to

make money—your pa’s paying a queen’s ransom for it, I can tell you that.”

When the youngest daughter was five years old, her mother

died. She had bet one of her hunting friends she could leap a half-broken colt

over a farm cart. She had lost the bet and broken her neck. The colt broke both

forelegs and had to be shot.

The whole city mourned, her husband and two elder daughters

most of all. The youngest one embarrassed her family at the funeral by

repeating, over and over, ‘‘Where is my mamma? Where is my mamma?”

“She is too young to understand,” said the grieving friends

and acquaintances, and patted her head, and embraced the husband and the elder

girls.

A well-meaning greenwitch offered the father a charm for his

youngest daughter. “She’ll work herself into a fever, poor little thing,” the

woman said, holding the little bag on its thin ribbon out to him. “You just

hang it round her neck—I’d do it myself, but it’ll work better coming from your

hands—and she’ll know her mamma’s gone, but it won’t hurl till she’s a little

more ready for it. It’ll last three, four months if you don’t let it get wet.”

But the merchant knocked the small bundle out of the woman’s

hand with a cry of rage, and might have struck the greenwitch herself—despite

the bad luck invariably attendant on any violence offered any magic

practitioner—if those standing nearest had not held him back. The startled

greenwitch was hustled away, someone explaining to her in an undertone that the

merchant was a little beside himself, that grief had made him so unreasonable

that he blamed his wife’s soothsayers for not having warned her against her

last, fatal recklessness, and had for the moment turned against all magic. Even

her pet dragon had been given away.

The greenwitch allowed herself to be hustled. She was a

kindly woman, but not at all grand—greenwitches rarely were—and had known the

family at all only because she had twice or three times found the youngest daughter

in a flowerbed in one of the city’s municipal parks and returned her to her

distracted nurse. She gave one little backward glance to that youngest daughter,

who was still running from one mourner to the next and saying, “Where is my

mamma? Where is my mamma?”

“I don’t like to think of the little thing’s dreams,”

murmured the green witch, but her escort had brought her to the cemetery gate

and turned her loose, with some propelling force, and the greenwitch shook her

head sadly but went her own way.

The night of her mother’s funeral her youngest daughter had

the dream for the second time. She was older in the dream just as she was in

life; older and taller, she spoke in complete sentences and could run without

falling down. None of this was of any use to her in the dream. The candles were

still too high overhead to cast anything but shadows; she was still all alone,

and the unseen monster waited, just for her.

After that she had the dream often.

At first, when she cried out for her mamma, the nurses were

sympathetic, but as the months mounted up to a year since the funeral, and no

more than a week ever passed before another midnight waking, another sobbing

cry of “Mamma! Mamma!” the nurses grew short-tempered. The little girl learnt

not to cry out. but she still had the dream.

And she eluded her protectresses more often than ever and

crept out into the garden, where the old gardener (keeping a wary eye out for

the descent of a shrieking harpy from the nursery) taught her how better to

plant things, and which things to plant, and what to do to make them happy

after they were planted.

She grew old enough to try to flee, and so discover that

this did her no good in the dream; it was the same dark, silent, sinister corridor,

without windows or doors, the same unknown, expectant monster, whichever way

she turned. And then she discovered she had never really tried to nm away at

all, that she was determined to follow the corridor to its end, to face the

monster. And that was the most terrifying thing of all.

She wondered, as they all three grew up, if it was the dream

itself that made her so different from her sisters. They were all beautiful;

all three took after their mother. But the eldest one was as brave as she had

been, and her name was Lionheart; the second one was as clever as she had been,

and her name was Jeweltongue. The youngest was called Beauty.