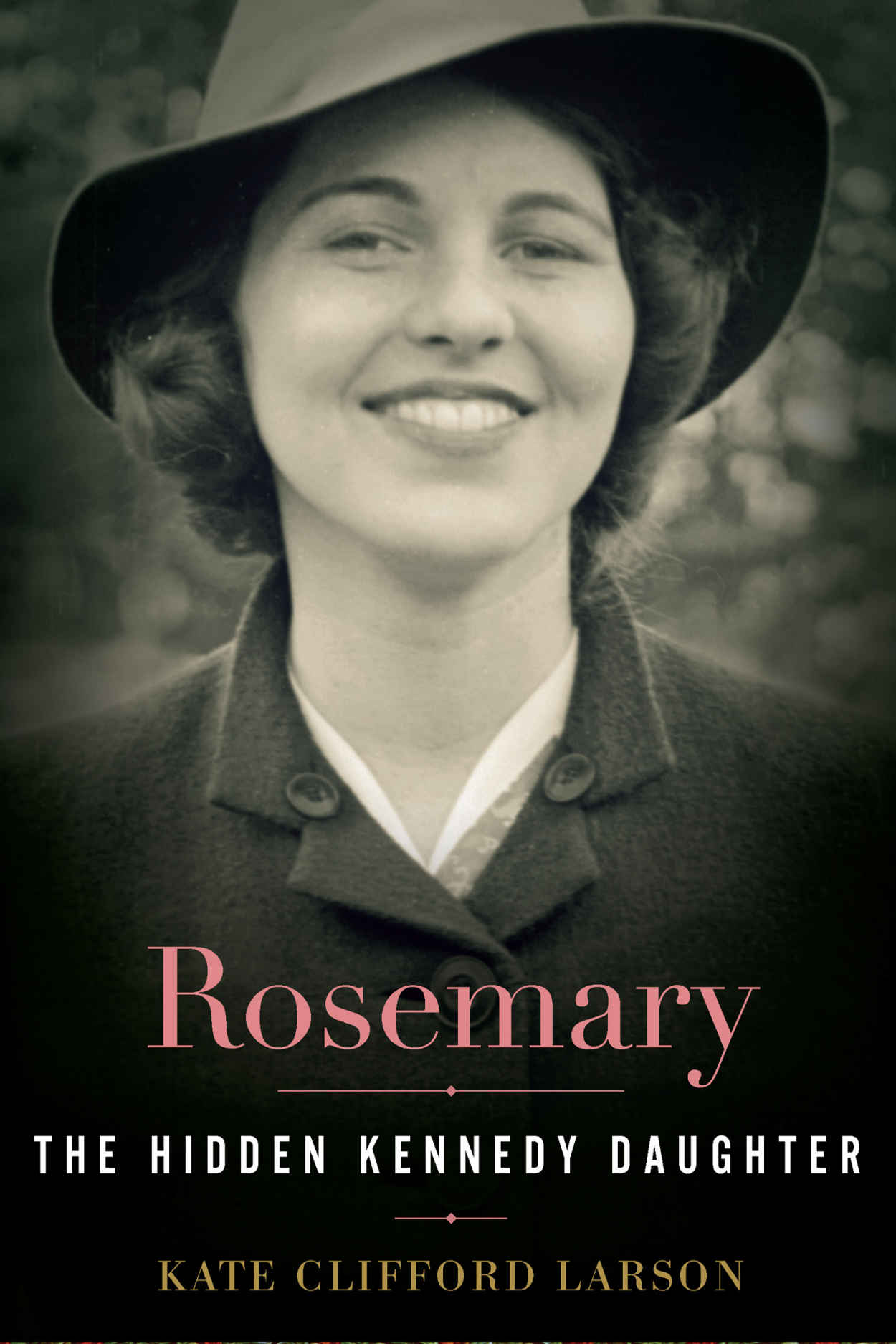

Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter

Read Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter Online

Authors: Kate Clifford Larson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #JFK, #Nonfiction, #Retail

Copyright © 2015 by Kate Clifford Larson

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN

978-0-547-25025-0

Cover design by Michaela Sullivan

Cover photograph © John F. Kennedy Library Foundation

e

ISBN

978-0-547-61795-4

v1.1015

To those struggling with disabilities and mental illness, and the families who love them

1

R

OSE KENNEDY, PREGNANT

with her third child, felt her contractions beginning on Friday, September 13. The nurse hired to attend her during the last days of her pregnancy quickly sent for Dr. Frederick L. Good, Rose’s personal obstetrician, to come to the Kennedy home at 83 Beals Street in the Boston suburb of Brookline. The first two Kennedy children, Joseph Jr., now three years old, and sixteen-month-old “Jack,” had both been born at home, and Rose was electing to do the same with this baby. It had been an uneventful third pregnancy. The deeply devout Rose would have been acutely aware of the gift of such a healthy pregnancy in the midst of great danger.

During the war years of 1917 and 1918, Spanish influenza swept the globe, killing tens of millions worldwide and debilitating millions more. By the fall of 1918, the flu’s deadly march was taking its toll on the citizens of Boston. By mid-September there were more than five thousand diagnosed cases of the Spanish flu in the city alone. Deaths mounted daily as the pandemic made its second of three deadly passes across the nation in less

than a year. The closing of theaters, lyceums, halls, and churches became mandatory, and public gatherings were discouraged to avoid the spread of the disease. Local hospitals, clinics, and doctors’ offices around Boston and its suburbs were overwhelmed.

Unlike other flu epidemics, which claimed mostly the lives of the very young and the very old, this viral infection took the lives of healthy young men and women in the prime of their lives as well.

Young soldiers who had survived the trenches and battlefields of Europe during World War I and returned home triumphant began dying by the thousands from pneumonia and respiratory failure. According to one nurse who worked day and night during the worst of the epidemic in Boston, “All the city was dying, in the homes serious illness, on the streets funeral processions.”

Nearly seven thousand residents died within a six-month period.

But the lethal virus did not infect the home of Joseph and Rose Kennedy and their young family. The nurse had been checking the unborn baby’s and Rose’s health daily, listening to both baby’s and mother’s heart rates, monitoring the baby’s position vis-à-vis the birth canal and its in utero activity, noting the details in a ledger for the doctor to review when he arrived. With Rose’s labor begun and Dr. Good sent for, she transformed Rose’s room into a modified antiseptic hospital labor room, ordered the general maid or hired girl to heat water, and made sure that all instruments and equipment the doctor might need were within reach.

Trained in the latest obstetrical nursing practices, the nurse was responsible for two patients, as her nursing manual would have reminded her: the mother and the unborn child. “If during the absence of the doctor the mother should die,” the

Obstetrical Nursing

guide warned ominously, “upon the physician’s return the nurse . . . could hardly excuse herself to the physician or to the

family.”

This directive put the nurse in an untenable position: she had been trained to deliver babies but also to wait for the doctor to arrive to deliver the baby. She could not give Rose an anesthetic as labor became more intense and painful, because only the physician and his anesthetist, in this case probably a Dr. Edward J. O’Brien, could administer anesthesia as a matter of course when they arrived.

But on this day, the doctor had not arrived once the baby began entering the birth canal, and Rose could not resist the need to push the baby with each more forceful contraction. The nurse tried to keep her calm, encouraging her to endure each contraction and to fight back the urge to push. Yet Rose’s baby started crowning, a crucial point in the birthing process. It was well understood that preventing the movement of the baby through the birth canal could cause a lack of oxygen, exposing the baby to possible brain damage and physical disability.

The doctor was delayed, caught up in attending his many patients stricken by the deadly flu. The nurse demanded that Rose hold her legs together tightly in the hope of delaying the baby’s birth.

Despite her training as an obstetrical nurse, she opted not to deliver the baby herself.

“I had such confidence in my obstetrician,” Rose wrote as a much older woman. “I put my faith in God . . . and tried to sublimate my discomfort in expectation of the happiness” she expected to feel once the baby was born.

Dr. Good and his colleagues, however, may not have been driven wholly by the desire to provide the best care for their patients. Fees derived from supplying health services to Boston’s social and economic elite provided a steady, and hefty, income in the days before medical insurance. If Dr. Good missed the birth of the baby, he could not charge his extremely high fee of $125 for prenatal care and delivery.

When

holding Rose’s legs together failed to keep the baby from coming, the nurse resorted to another, more dangerous practice: holding the baby’s head and forcing it back into the birth canal for two excruciating hours.

The doctor did finally appear at the Kennedys’ home, and at seven in the evening he delivered Rose’s seemingly healthy third child. The

Boston Globe

announced the birth: “A dainty girl was added to the nursery which previously sheltered two sturdy sons.”

Flowers and cards of congratulations poured in. The baby would be named for her mother. Little Rose Marie Kennedy—“Rosie” to the family, and later called Rosemary—would be loved and nurtured by both of her parents.

Rosemary was “sweet and peaceable and cried less than the first two,” Rose would recall more than fifty years later.

Rose spent several weeks “lying in,” the length of time middle- and upper-class women took to recover from childbirth. New mothers, it was recommended, should rest and remain in bed for at least nine days and slowly begin daily activities, like walking, over a period of many more days, increasing activity gradually over several weeks. Six weeks was considered ideal. Rose enjoyed this time alone, nursing and doting on baby Rosemary. Full-time and part-time nursemaids and other household help took care of the boys, cleaned, and cooked. “The quiet and peace surrounding the mother and child at this period is good for both,” Rose later wrote about this time alone with her newborn baby.

J

OSEPH “JOE” P. KENNEDY SR

., as the new assistant general manager of the Fore River Shipbuilding Company, a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel in nearby Quincy, could afford such luxuries for his wife. Most men of his age—Joe was thirty years old when his first daughter was born—were now required to register for

the wartime draft. But he was exempt from military service because of his role working for the shipyard and managing its multimillion-dollar government contracts and thousands of workers now building naval vessels destined for the war in Europe. Joe was brilliant at his job, and his business and management acumen spurred the expansion of not only the shipyard and its workforce but also the support systems required to shelter, feed, and transport the thousands of workers at the plant. Joe’s workload increased “exponentially” at this time, keeping him working lengthy days and often not returning home for the night, establishing a work ethic that would persist for the rest of his life. This pace, however, earned Joe an ulcer, and just a month after Rosemary was born he checked himself into a sanitarium to recuperate.

Persistent ulcers and other intestinal issues, too, would plague him until his death.

The 1914 marriage of Rose, the beautiful and intelligent eldest daughter of Boston’s mayor, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, and his wife, Mary Josephine “Josie” Hannon, to Joe, the scion of a politically powerful East Boston family, had signified a strong political and economic union. It was a foundation from which the couple rapidly ascended to the pinnacle of Boston’s newly established Irish social, political, and economic elite.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, two generations earlier, the North End of Boston had become a community of immigrants and the working poor whose interests and needs varied greatly from the native-born Brahmin and Yankee aristocracy. This group, whose ancestors had settled Boston centuries before, shaped New England culture and society. Its Puritan legacy informed the region’s politics, education, social interactions and relationships, economics, and the very landscape of cities and towns where immigrants settled to build new lives. The historic

neighborhoods of some of Boston’s founding families included the Brahmin stronghold of Beacon Hill. The south side of the hill, dominated by the Massachusetts State House, faces the city’s common and public garden. Powerful business, political, and literary leaders lived in the neighborhood mansions, forming a distinctly Protestant aristocracy. The mere one hundred acres of the North End, located on the northern reaches of the city and bordered by the Charles River and Boston Harbor to its north and east, respectively, was one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the country. In 1860, nearly twenty-seven thousand people crowded its crooked streets and lanes. More than half were Irish immigrants. During the latter quarter of the century, however, a tidal wave of eastern European immigrants fleeing political, economic, and agricultural disasters and massive anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia and other nations provided a steady flow of desperate and hopeful people. In sharp contrast to Beacon Hill—a half mile away—the North End’s tenements and sweatshops teeming with people spilled out onto streets and wharves.

The congestion in such a small area placed terrible stress on the entire city and its residents. In spite of the benefits of a bustling economy, sewage, garbage, and low-wage maritime, industrial, and textile businesses plagued the health and well-being of individuals and families in the crowded district. The economic and human costs were great. Classrooms were horribly overcrowded, filled with children from myriad ethnic and racial backgrounds who spoke dozens of distinct and different languages. The city scrambled to accommodate them; it was imperative that they be taught English and good work habits, and that they become “Americanized” as quickly as possible, native-born elites believed. Eager to impart white, middle-class Protestant confor

mity, many city public schools were open eighteen hours a day to provide programs not only for two shifts of daily classes for children of all ages but for their parents, too.

Such densely packed buildings and streets eventually drove the young Fitzgerald family out of the North End, where Rose’s father, John Fitzgerald, had grown up as the fourth of twelve children. Rose’s mother, Josie Hannon Fitzgerald, was from Acton, a rural farming community twenty-five miles west of Boston. After the couple’s marriage, they settled in the North End, but Josie longed for the green grass and fresh air of the countryside. In 1892, when Rose was two years old, Fitzgerald yielded to his wife’s wishes and bought a large house for his family in West Concord, three short miles from Acton but thirty miles from Boston. Like many of their Irish neighbors, the Fitzgeralds left behind the rickety wooden and dilapidated brick tenements of their poorer neighbors for more space, inside and out, and more refinement. Between the late 1890s and 1920, the West End of Boston, Brighton, Roxbury, Dorchester, and Hyde Park experienced tremendous growth and development, prompting the annexation of these communities by the city proper. The construction of an elevated railway and subway system in Boston in 1897 made these areas more easily accessible to the city and to jobs.