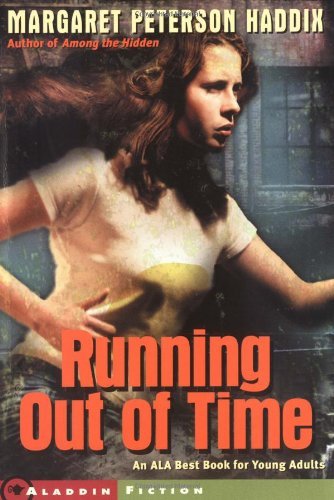

Running Out of Time

Read Running Out of Time Online

Authors: Margaret Peterson Haddix

Margaret Peterson Haddix

简介

Run For Your Life.....

The village children are dying and Jessie's mother is desperate for medicine to save them. But it is 1840 and no such remedy yet exists. Except that it is 1996, and all this time Jessie's world has actually been a living history museum. Now she must escape to the 20th century to get help.

Age Level: 8 and up

RUNNING OUT OF TIME

MARGARET PETERSON HADDIX

To Doug, and in memory of Myrtle Peterson

With thanks to Marilee Peterson, Dr. K. W. Chan, and

Creg Stockwell for help with medical and pharmaceutical information.

The light woke Jessie, though it was just a glimmer downstairs. She eased out of bed, being careful not to disturb her sister Hannah.

"Ma?" Jessie whispered by the ladder down from the loft. In a few moments, her mother's tired face appeared below, illuminated by a flickering candle.

"It's the Bentons," she said. "Caleb says both Sally and Betsy are sick."

Everybody called Jessie's mother "the midwife," but she did a lot more than deliver babies. In Clifton, anyone who got sick at night called on her. Most people, Jessie thought, seemed to wait until dark to get sick, so they wouldn't have to go to Dr. Fister. Dr. Fister always gave prescriptions like "Make a poultice of chokeberries and rub it on your neck three times a day." He made a real show of it. He used to slip

a packet of pills under the table, too—pills that really worked. Anymore, though, he just gave the folk remedy. Jessie hadn't seen any of the pills in a long time.

"Can I come and help?" Jessie asked Ma.

"I don't want you catching anything. . . ."

Jessie gave her mother what Pa called "that pitiful please look," and she relented.

"All right. You can carry my bag. But I don't want you coming inside until I find out what Sally and Betsy have."

Jessie pulled her dress off the nail by her bed and yanked it over her head. Then she scrambled down the ladder and took her boots from beside the door. She was ready by the time Ma finished dressing. Grown women had to worry about clothing more than thirteen-year-old girls did. That was one reason Jessie was glad she wasn't entirely grown-up yet.

Ma unlatched the door and they slipped out into the warm April night.

"Hannah and the boys never even moved!" Jessie said.

Ma smiled.

"They could sleep through a blizzard. You're my light sleeper. You're always afraid you might miss something."

Jessie grinned. It did seem like an adventure being out in the middle of the night. The village looked spooky with only moonlight and the faint glow of Ma's lantern. Shadows flickered on the path and in the surrounding woods. The main buildings of Clifton loomed like hulking animals. Jessie shivered passing the three trees in the square that everyone said were haunted.

"Did Caleb go on home?" Jessie asked. Caleb Benton was a ten, but he was the biggest chicken in Clifton School. "1 bet he was scared—"

"His ma didn't want him to wait," Ma said.

Jessie waited for Ma to say more, but she didn't. Usually when Jessie convinced Ma to let her go along on these night trips, Ma and Jessie talked all the way: about the symptoms Ma knew and how she planned to treat them, or about Jessie's schoolwork, or about just anything. But tonight Ma seemed barely aware that Jessie was with her. Ma stepped silently, her face shadowed. Jessie thought Ma might just be tired. This was the fourth night in a row she had been called out. Ma hadn't let Jessie go the other times.

They passed the school, the general store, and Dr. Fister's clapboard house. Jessie couldn't understand how the doctor could afford a clapboard house, when no one went to him. Jessie's pa was the blacksmith, and he was always busy. Yet Jessie's family still lived in the log cabin they'd built back in 1828, when they first came to Clifton. Jessie had hinted more than once that they needed a new house, now that there were six children. After all, she said, little Katie was soon going to outgrow the trundle bed that slipped under Ma and Pa's bed downstairs. Where was Katie going to sleep then?

Pa always answered that a new house was too expensive, with the whole country in a depression. He didn't seem to mind. Hannah whispered that Pa liked the log cabin too much to build a house.

Hannah was just a year older than Jessie, but she said she could remember when they built the cabin. All the men in the village helped lay the maple logs, one on top of another, and then the women filled the cracks with mud. Jessie had

seen other cabins built—had helped, even—and thought Hannah might just be confused. Even Hannah couldn't remember before, when they'd lived in Pennsylvania. Jessie wished she could remember the trip out to Indiana, when she and Hannah and Ma and Pa had traveled down the Ohio River in a flatboat. Sometimes she could get Pa to tell about it. Ma never would.

"Be careful," Ma said as Jessie tripped over a root in the path.

"It's hard to see," Jessie said. The moon was behind a cloud now.

Ma nodded and moved the lantern closer to Jessie. They were almost to the Bentons' cabin.

"Do you think Sally and Betsy will be all right?" Jessie asked. Sally was prissy, kind of like Hannah, but Betsy was always fun to play with.

"I hope so," Ma said, in a way that made Jessie worry. A lot of children were sick: Jefferson Webster, Susan Seward, Abby and James Harlow. Jessie knew it wasn't just the usual spring chills and fevers. There were too many empty seats at school.

"Wait here," Ma said, pointing to a stump in front of the Bentons' cabin. She gave Jessie the lantern and knocked lightly on the door. It opened immediately. Jessie caught a glimpse of Mrs. Benton, crying. Mrs. Benton was a tall woman with rough hands. Jessie had never seen her cry.

Jessie went to the Bentons' oilpaper window, but she could see only shapes moving. The Ma shape seemed to be bent over the bed downstairs. They must have put Sally and Betsy in Mr. and Mrs. Benton's bed. That was serious.

The Bentons and Ma talked in such low voices Jessie couldn't hear anything. And she'd get in trouble if they knew she was trying to listen. She sat down on the stump, placing the lantern on the ground in front of her. She should put it out, to save the oil, but it was a comfort. Everyone said bears and wolves stayed away from fire. All sorts of rustling noises came from the woods beyond the Bentons' cabin.

Normally Jessie wasn't scared of wild animals. She was braver than anybody; she took more dangerous dares than the boys at school. But all this sickness and the way Ma was acting worried her. Jessie wished someone would explain what had happened to Dr. Fister's pills. Even when he'd had them, people pretended they didn't exist. But they always worked. Why weren't there pills for Betsy, Sally, and the others?

It was another mystery of Clifton, Jessie thought, like the haunted trees.

Once, when Jessie was little, she'd noticed a box at the top of one of the haunted trees. It was painted the same color as the branches, but it held a piece of glass that sometimes glinted in the sunlight. The box moved constantly, even when there wasn't a breeze. Jessie had been so curious that she started climbing the tree. She'd only gotten her right leg up on a branch when Mr. Seward ran out of his store and ordered her down. At first, Jessie thought it was funny to see the big man run. But she didn't laugh long. Mr. Seward spanked her, hard, and then Pa spanked her when she got home. Both of them shushed her whenever she tried to say something about the box.

After that, the box disappeared and was replaced by a

piece of glass in one of the limbs. Jessie never told anyone she saw it. But she would have loved to look at it up close.

The thing was, neither Mr. Seward nor Pa had seemed surprised when Jessie told them about the box. Did adults everywhere have so many secrets, or was it just in Clifton? Except when she was a baby, Jessie had never been any farther away from Clifton than a few miles up the hill to pick blackberries. So she had no way of knowing. Only, the adults in Clifton seemed to be acting more and more strangely lately. They'd confer in whispers, then pretend nothing was going on. Pa had told Jessie that everyone was worried about the depression, which started back in 1837 and didn't seem to have an end in sight.

Jessie could understand people being worried about that—Pa said even the state had gone bankrupt. But she still suspected the adults were whispering about something else. What could it be?

Sometimes Jessie wanted to be an adult right away, so she could learn all the secrets. And sometimes she never wanted to grow up.

Jessie giggled, thinking of the fight she'd had just that day with Hannah. Hannah said the only reason to grow up was to get married and have children.

"Who wants to cook and clean all day? I'm going to be a doctor," Jessie had said.

"There's no such thing as a woman doctor," Hannah said.

"I'll be the first, then!"

Hannah laughed at her, so Jessie teased her about being in love with Chester Seward. Was she ever mad about that! It was true, though. And Chester never even looked at Hannah.

Jessie had overheard Hannah ask Ma if she would be an old maid if she wasn't married by sixteen, like Mr. Seward said. Hannah could be so stupid. Jessie wouldn't care if she never got married.

"Jessie?"

Ma was out the Bentons' door now. Jessie stood and picked up the lantern.

"Can I help, Ma?"

"We need to go out to the woods to pick some, uh, herbs."

It made no sense—they had every herb imaginable dried and hanging from the rafters at home. But Ma had a strange look on her face that told Jessie not to ask questions. Behind her, Mr. Benton came out and nailed a paper sign to the door. It had one word that Jessie could barely make out in the light: quarantine.

"What's a quarantine?" Jessie asked. It looked like the kind of word Mr. Smythe, the schoolmaster, would put on the eighth-grade spelling list. But Jessie had never seen it.

"It's a word to let people know there's a dangerous disease inside, so they should stay away," Ma said. "Mr. Benton's going to tell the Websters and the Harlows to put out signs, too."

"Not the Sewards?"

Ma shook her head and put her finger to her lips. Another secret.

Ma and Jessie walked into the woods in silence. They passed plenty of herbs, but Jessie decided not to ask what they were looking for. Ma was acting too strangely.

Finally they stopped beside a huge rock that Jessie and her friends had played King of the Mountain on, before it was

forbidden. Ma bent down at the base of the rock. There was nothing but dirt there, but she motioned for Jessie to crouch, too.

Then, when Jessie had doubled over, her cheek pressed against the cold rock, Ma began to whisper.

"I may have to ask you to do something very dangerous," Ma said.

Jessie felt a chill.

"What?"

Ma shook her head impatiently.

"You can't ask questions now. We may be able to avoid it. The signs may work."

A thousand questions came to Jessie's mind, but she obediently pushed them away. Ma smiled, grimly.

"After school tomorrow, I want you to tell everyone you have to look for more herbs. Don't let anyone come with you. I'll meet you here as soon as it's dark."

"Why?" Jessie couldn't help asking.

"I'll tell you then. If I'm not here, everything's fine and you can just go home."

"But—'"

"It's important that you do exactly what I say. And don't tell anyone."

None of it made sense, but Jessie nodded. Then Ma turned away. She picked a few leaves without even looking to see what they were.

"Wake up, sleepyhead!"

Jessie groaned. How could it be morning already? But Hannah was standing over the bed, all dressed, her brown hair neatly braided and wrapped around her head. Even in the uncertain light of the loft, Jessie could tell by her sister's red cheeks that Hannah had scrubbed her face hard enough for both of them.

"You're not going to have time for chores if you don't hurry up," Hannah said. "I don't know why some people need years of sleep."

Jessie started to answer that "some people" had done more interesting things than sleep all night, but then she stopped. No one was allowed to mention Ma's midnight rounds during the day. It was another secret, though everyone knew about it.

Jessie sat up and remembered that last night was doubly secret. What was the "something very dangerous" that Ma wanted her to do?

Jessie had done pretty much everything dangerous there was to do in Clifton, she thought, without being killed. On a dare, she'd walked a fallen oak tree across Crooked Creek last May when it was flooded. Everyone was sure she'd fall off and drown in the speeding water. But Ma wasn't supposed to know about that. Jessie had also talked Pa into letting her help him shoe Mr. Meders's wild horse once, and the horse had reared and kicked his hooves at her. But Pa had pushed her out of the way then. Jessie couldn't imagine either of her parents actually putting her in danger.

"Jessie—" Ma called from downstairs.

"Coming," Jessie said.

Hannah flashed her an "I told you so" look and disappeared down the ladder. Jessie thought about throwing her brush at Hannah, but didn't want to take the time to pick it up. And she would get in trouble. Hannah would see to it.

Jessie got out of bed and pulled her dress on, no more carefully than she had the night before. The dress was a threadbare woolen that had originally been Ma's; it was cut down for Hannah and then passed on to Jessie when Hannah became too stout. Jessie didn't think it was fair that she still had to wear Hannah's old clothes. Jessie was an inch taller. It wasn't her fault Hannah was fatter. But people in Clifton didn't care about a girl's ankle showing a little. She'd heard Ma and the other women say it was a scandalous thing back East, but on the frontier people had other things to worry about.

Wondering whether she'd ever have a chance to see the East, Jessie began her daily battle with her hair. It was dark and coarse and uncontrollable. Jessie braided it as tightly as she could, knowing wisps of hair would begin freeing themselves as soon as she finished.

Finally ready, Jessie climbed downstairs and started taking the family's chamber pots out to the outhouse. She hated that chore, but it was her turn. Two of her brothers, Nathan and Bartholomew, were helping Pa feed the cattle, pigs, chickens, and horses. Andrew, who was just two years younger than Jessie, carried wood toward Pa's blacksmith shop. Hannah and Katie, the youngest, helped Ma with breakfast.

Jessie stopped at the well to wash her hands. Pa, heading from the barn to the forge, stepped behind her.

"Morning, Jessica. Did milady sleep well?"

It was his joke, to call his daughters "milady," even though he didn't believe in royalty. Jessie had heard Mrs. Seward say once that, for a Jacksonian Democrat, Joseph Keyser certainly put on airs.

"Yes, Pa," Jessie said. She looked at him closely, trying to figure out if he knew about the "something very dangerous" that Ma wanted.

"What's wrong? Did I forget to shave?" Pa made a show of trying to look down at his chin. Jessie decided he didn't know anything about Ma's plans. That scared her, but she clowned an answer.

"I think you missed a patch right there—" Jessie said, pointing at a spot on his right cheek and bringing her hand up suddenly to splash water on his face.

Pa laughed and splashed her back.

"Pa! I don't want to be soaking wet at school!" Jessie protested.

"You started it!"

Jessie dried her hands on her apron as Pa, laughing, went on to the smithy. Jessie had heard Ma complain that Pa acted worse than the little boys sometimes. With his curly brown hair and laughing eyes, he looked a lot like Nathan. Jessie knew he was actually thirty-five, because it said in the family Bible, "Joseph Andrew Keyser, born May 18, 1804, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania." Ma was three years younger, but she acted older. The circuit rider minister, Reverend Holloway, always preached that wives were supposed to be obedient to their husbands. It didn't seem to work that way at Jessie's house. Oh, Ma pretended to be obedient, but she was really in charge.

Only, Pa usually knew what she was planning.

Jessie walked slowly back to the house, stumped about what Ma might want her to do. Usually Jessie could find some answer to any question at school, even when she wasn't entirely sure. But she couldn't figure out anything now. In the sunny yard, Jessie almost wondered if she'd imagined going to the King of the Mountain rock. Had she dreamed it? But no—when she stepped in the cabin door, she saw the wilted leaves Ma had picked on their way out of the woods.

"No dawdling, now," Ma said as everyone converged at the table. Jessie could smell the salt ham from across the room. There were also eggs, biscuits, gravy, back bacon, apple pie, and mush.

The light from the fire glowed behind the table. The cabin was dim otherwise, because the oilpaper windows were so

thick. Often Jessie wished for glass windows like Dr. Fister's, but today the dimness seemed cozy. Across from the door, the ornate mirror on the back wall reflected little light. Even if it was one of the few heirlooms brought from Pennsylvania, Jessie had never liked the mirror. Maybe she'd been yelled at to stay away from it too many times when she was younger. But she'd been told just as often to be careful around the framed picture of Andrew Jackson and the tacked-up map of the United States, which hung on either side of the cabin door. And she had always thought the map and the picture looked downright friendly.

Pa began his prayer. As always, it was long, and Jessie wasn't the only one to open one eye and peek at the food.

"We implore you, Lord, to keep our village and family safe from any sickness abroad in the land," Pa said. Jessie glanced up, but Pa's face wasn't any different from when he prayed for the wisdom of the government.

Jessie caught a stern glance from Ma and closed her eyes again until the "Amen."