Russell - A Very Short Indroduction

Russell: A Very Short Introduction

Very Short Introductions are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide.

The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology.

A. C. Grayling

RUSSELL

A Very Short Introduction

Contents

Preface viii

Abbreviations x

List of illustrations xii

1

Life and work 1

2

Logic and philosophy 29

3

Philosophy, mind, and science 61

4

Politics and society 85

5

Russell’s influence 120

Further reading 139

Index 141

Preface

Russell lived long and did much. He is one of the relatively small number of philosophers whose names are popularly known, and who in their life and work have come to seem emblematic of the great tradition of thought they represent. The reputation Russell enjoyed among his contemporaries rested on the multiplicity of contributions he made – often highly controversial ones – to social, moral, political, and educational debates. But his claim to an enduring fame rests on his outstanding technical contributions to logic and philosophy. In what follows I survey his life’s work in both spheres. The aim throughout is to give as clear an account of them as brevity allows. Because this is not the place for detailed evaluation of philosophical arguments, still less of technicalities in mathematical logic, I give most houseroom to exposition; but I venture some discussion also, the themes of which can be pursued by consulting the literature cited in the Further reading section, which shows the way for anyone who, having paddled in the surf here, might like to go for the swim. However, readers not especially interested in the more technical reaches of logic and philosophy can forgo chapters 2 and 3, and can concentrate instead on the story of Russell’s life and his contributions to public debate, as told in chapters 1 and 4.

I am grateful to Keith Thomas and the Press’s keen-eyed reader for comments, to Ken Blackwell for prompt help and documents from the Russell Archive, and to Alex Orenstein and Ray Monk for related and relevant discussion. My thanks go also to Leena Mukhey for her work on the index.

This is dedicated to Sue

–

‘

dulces dominae Musa Licymniae cantus, me voluit dicere

’.

A.C.G.

London

1996

Abbreviations

Russell wrote much, and his work has been reprinted often and in a variety of editions, the paginations of which do not always agree. Here are the principal works cited in the text in the editions consulted, with the abbreviations employed for those most frequently occurring.

A The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell

, one-volume edn. (Unwin Paperbacks, 1975)

AMd The Analysis of Mind

(Allen & Unwin, 1921)

AMt The Analysis of Matter

, paperback edn. (Routledge, 1992)

HK Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits

(Allen & Unwin, 1948)

HSEP Human Society in Ethics and Politics

(Allen & Unwin, 1954)

PLA

‘The Philosophy of Logical Atomism’, in

Logic and Knowledge

, ed. R. C. Marsh

MM Marriage and Morals

, paperback edn. (Routledge, 1991)

MPD My Philosophical Development

, paperback edn. (Routledge, 1993)

OKEW Our Knowledge of the External World

, 2nd edn. (Allen & Unwin, 1926)

PM Principia Mathematica

, 2nd edn. (Cambridge University Press, 1925)

PoM The Principles of Mathematics

(Allen & Unwin, 1937; first published 1903)

PP The Problems of Philosophy

(Oxford University Press, 1912)

An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth

(Allen & Unwin, 1940)

The Conquest of Happiness

(Allen & Unwin, 1930)

Education and the Social Order

(Allen & Unwin, 1931)

Essays in Analysis

, ed. Douglas Lackey (Allen & Unwin, 1973)

Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy

(Allen & Unwin, 1919)

Logic and Knowledge

, ed. R. C. Marsh (Allen & Unwin, 1956)

Mysticism and Logic

, paperback edn. (Allen & Unwin, 1963)

Power

(Allen & Unwin, 1938)

Principles of Social Reconstruction

(Allen & Unwin, 1916)

Religion and Science

(Oxford University Press, 1935)

Why I Am Not A Christian

(Allen & Unwin, 1957)

Political Ideals

(Routledge, 1994; first published 1917)

Roads to Freedom

(Allen & Unwin, 1918)

Portraits from Memory

(Allen & Unwin, 1958)

Chapter 1 Life and work

Russell is one of the best-known philosophers of the twentieth century. His fame – at times, his notoriety – was chiefly the product of his engagement in social and political controversy. He was a familiar public figure for nearly 60 years, featuring in the popular press sometimes as a subject of scandal and sometimes, in his respectable periods, as a pundit; in which role he also appeared as a broadcaster. He had much to say about war and peace, morality, sexuality, education, and human happiness. He published many popular books and articles, his views earning him a wide range of responses, from prison sentences to a Nobel Prize.

But his greatest contributions, and the true basis of his reputation, lie in the technical fields of logic and philosophy. So pervasive is his influence both on the matter and style of twentieth-century English-speaking philosophy that he is practically its wallpaper. Philosophers use techniques and ideas developed from his work without feeling the need – sometimes without recognizing the need – to mention his name; which is influence indeed. In this way he is a far more significant contributor to philosophy than his pupil Ludwig Wittgenstein. Philosophy learned some valuable lessons from Wittgenstein, but from Russell it acquired an entire framework, constituting what is now called ‘analytic philosophy’.

This label ‘analysis’ means rigorous examination of philosophically important concepts, and the language which embodies them, using methods and ideas derived from formal logic. Russell did not, of course, create analytic philosophy unaided. He was influenced by the logicians Giuseppe Peano and Gottlob Frege, and by his Cambridge colleagues G. E. Moore and A. N. Whitehead. Other influences were the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers René Descartes, Gottfried Leibniz, George Berkeley, and David Hume. Indeed his first philosophical book was a sympathetic study of the second of these. But he brought these influences together in such a way that they offered a new approach to philosophical problems, illuminating them by a sharp new logical light. By this means he played a central role in revolutionizing twentieth-century philosophy in the anglophone tradition.

Russell was accordingly a philosopher in both the popular sense, as a sage and teacher of mankind, and in the professional academic sense. In the chapters that follow I describe his contribution in both these philosophical guises. In the present chapter I sketch his long, rich, and sometimes tumultuous life, which in its sum and variety constitutes one of the most heroic biographies of modern times.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born on 18 May 1872 into a famous family, a cadet branch of the Dukes of Bedford. His paternal grandfather was the celebrated Lord John Russell who introduced the Reform Bill of 1832, which was the first step towards democratization of Parliament. Lord John was twice Prime Minister – from 1846 to 1852 and from 1865 to 1866 – and was raised to an earldom by Queen Victoria. Russell’s maternal grandfather, Lord Stanley of Alderley, had been a political ally of Lord John.

Russell’s parents were an unusual and controversial couple, committed to progressive causes such as family planning and votes for women. His father, Viscount Amberley, chose John Stuart Mill as his godfather in a

1.

The Russell family in 1863, showing Dr Wagner, a tutor; Bertrand Russell’s uncle, William Russell; Lady Russell; Rollo Russell (another uncle); Georgy (Lord John’s daughter by his first marriage); Lord Amberley; Lord John Russell; and Agatha Russell (Bertrand Russell’s aunt).

non-religious sense. Mill died just before Russell’s first birthday, so his influence, though considerable, was indirect.

Amberley was briefly a Member of Parliament, but his political career collapsed when it became publicly known that he supported the idea of contraception. An example of the Amberleys’ advanced views is afforded by the case of D. A. Spalding, a clever young scientist employed as tutor to Russell’s elder brother Frank. Spalding was severely consumptive, and therefore in no position to marry and have a family. The Amberleys decided that this was no reason for him to be celibate, so Russell’s mother ‘allowed him’, as Russell puts it in his

Autobiography

, ‘to live with her’ – to which he adds, ‘though I know of no evidence that she derived any pleasure from doing so’ (

A

12).

Russell’s mother and sister died of diphtheria in 1874 when he was aged 2, and his father’s death followed 18 months later. Amberley had appointed two agnostics as guardians for his sons – Spalding was one of them – but their grandparents, Earl Russell and his wife, strenuously objected. They went to law to overturn Amberley’s will, and took their grandsons to live with them at Pembroke Lodge, a Royal grace-andfavour house in Richmond Park. Frank, seven years Russell’s senior, found life there intolerable, and rebelled. He was sent away to school. Bertie, more tractable and sweet-tempered, was kept at home. His grandfather died a mere three years later, and he was then entirely under the influence of his strait-laced Scottish Presbyterian grandmother, a daughter of the second Earl of Minto. Russell’s character has often been explained, even – when occasion seems to demand it – excused, by reference to his aristocratic origins; but its first moulding was more truly the work of his grandmother’s puritanism, characteristic rather of middle- than upper-class Victorianism. In the flyleaf of the Bible she gave him for his twelfth birthday she inscribed one of her favourite texts: ‘Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil.’ This remained a principle for Russell throughout his life.

It was a lonely but not, to begin with, an unhappy childhood. Russell had German and Swiss governesses, and early spoke German as fluently as English. He conceived a love for the extensive grounds of Pembroke Lodge, with their handsome views of the surrounding country. ‘I knew each corner of the garden,’ he wrote, ‘and looked year by year for the white primroses in one place, the redstart’s nest in another, the blossom of the acacia emerging from a tangle of ivy’ (

A

26). But as adolescence encroached, his isolation, intellectual as well as emotional, grew increasingly painful. He was alone in a household of old people remote from him in every way. A succession of tutors was his only tenuous link with the larger world. Nevertheless he was saved from too great unhappiness by nature, books, and, later, mathematics. One of his uncles had an interest in science, which he communicated to Russell, helping to spur his mental awakening. But the real epoch occurred

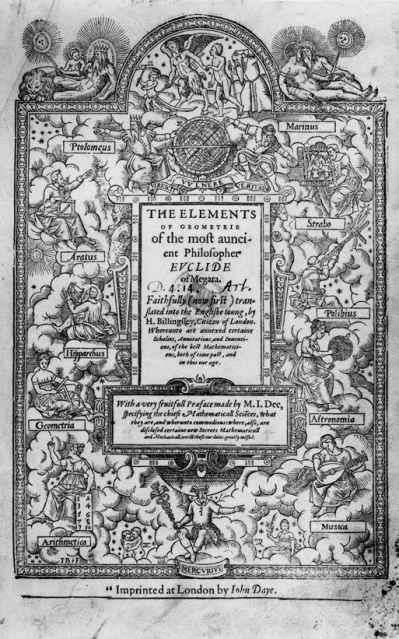

2.

2.

Frontispiece from

The Elements

, Euclid’s best-known treatise on mathematics.

when he was 11 years old and his brother began to teach him