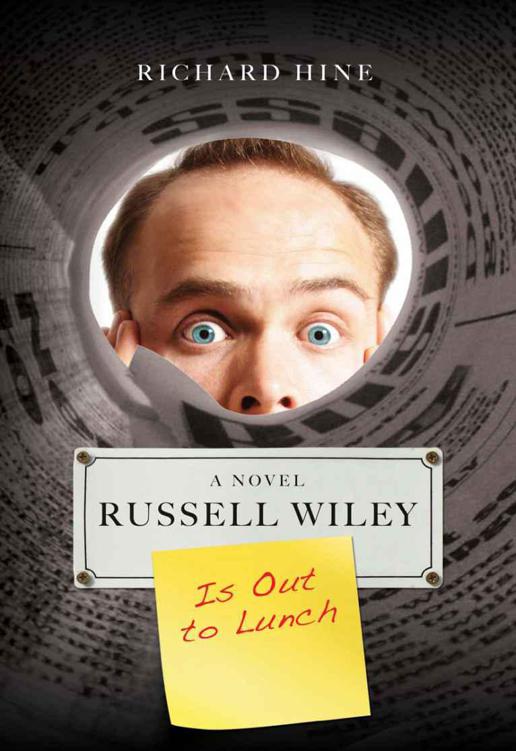

Russell Wiley Is Out to Lunch

RICHARD HINE

A NOVEL

RUSSELL WILEY IS OUT TO LUNCH

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright ©2010 Richard Hine

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by AmazonEncore

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-935597-14-8

For Amanda

“I often wonder what future historians will say about us. One sentence will suffice to describe modern man: he fornicated and he read newspapers.”

—Albert Camus, The Fall, 1956

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

New York City, Fall 2006

“I’m still asleep,” says Sam.

It’s the kind of thing she says on a morning like this. When she feels me lying in bed three minutes after I’ve silenced the alarm. When she senses me, curled next to her, mimicking her shape without actually touching her. She doesn’t want to move in case it encourages me.

Another minute goes by.

I put a hand on her hip, wiggle myself an inch or two closer. She sighs. I kiss the back of her head, savoring the smell of her coconut conditioner.

“Get off me,” she says.

She slides out from under the comforter and makes her way to the bathroom. I don’t get up. I wait. The toilet flushes, and as she pads back to bed I catch a glimpse of her: slightly tangled, shoulder-length hair; baggy purple T-shirt; a flash of white cotton panties. She slithers into her former position, adjusts her head against her pillow.

“Can’t we just cuddle?” I say.

“There isn’t time. Don’t you have a meeting? I haven’t brushed my teeth.”

I know better than to argue any of these points. Sam and I have been together more than sixteen years, married for nearly thirteen. I don’t remind her that in our early days together finding time for sex was never a problem. Or that I’ve survived being late for dozens of meetings. Or that once upon a time even morning breath possessed certain aphrodisiac qualities.

I roll away, sit on my side of the bed. My mind feels foggy, my vision is blurred. I grab my glasses and walk, head down, to the bathroom.

I shave slowly, cutting through the foam with one of those disposable triple-bladed razors. Sam used to hang out with me in the bathroom some mornings and tell me how sexy it was to watch me shave. I can’t remember the last time she did that.

I do remember the last time we had sex. Twenty-five days ago. One of those unsatisfactory occasions where I came and she didn’t and it was my fault for not holding on long enough and whoever said love means never having to say you’re sorry was proved wrong again. Despite that failure, I’d be happy to try again. I’m willing to practice more. To try and do it right next time.

Twenty-five days. Nearly four weeks. I’m not supposed to be keeping tabs anymore. But so what if I do? Days without sex is an important statistic—the kind that used to matter to Sam as well as me. Before we were married, even when we lived six hundred and fifty miles apart during senior year, we had an agreement never to let more than a month pass without having sex with each other. Whenever necessary, we each drove six hours to meet halfway at a roadside motel just outside Harrisburg. We’d make love in the shower, on the armchair, on the bathroom counter, on the bedroom floor. We’d drink beers, eat shortbread cookies and inspect each other’s bodies for crumbs. We’d sleep on the gray-white sheets, go out for pancakes, then head back to the room to take full advantage of the hours and minutes we still had left. When we parted, I’d drive home weak but elated, listening to the Pulp album that reminded me of the semester we’d shared in London. Every time I unpacked my bag, I’d find a piece of Sam’s clothing stuffed inside—panties, a bra, a single white sock. I kept these items in my bedside drawer.

Our relationship was easier to navigate then: a twelve-hour roundtrip came with a built-in guarantee. Nowadays, even though we sleep just inches apart, our love life requires far more elaborate maneuvers. Sex has become something we build up to slowly, not something we do on a whim. For Sam, things have to happen in a certain yet inexplicable order. It’s as if she’s got the whole thing choreographed in her mind, but every time I put a foot wrong the music stops and the whole dance has to begin again.

I step into the shower stall and blast myself with water that’s hotter than I usually like.

I towel off and stand naked in front of the bathroom mirror. I’m thirty-seven years old. My eyesight sucks. In the blurred reflection of my upper body I see the face of a cartoon dog—my nipples make two eyes above a round, belly-button nose and jowly, hanging cheeks. I put my glasses back on, hoping to make the face disappear, but the effect lingers.

I walk back into the bedroom.

“Do you think I’m fat?” I ask Sam. Now that I’ve showered and am focused on getting out the door, she can allow herself to display more signs of consciousness.

“No,” she says. “Of course not.” We both know that using the F-word can damage a relationship.

I pull back the curtain, trying to find some socks that will match the pants I plan to wear. I make the mistake of giving Sam a side view of my gut as I bend over.

“I just think you should work out more,” she says. “I worry about your health.”

That’s a good one. The worry-about-your-health angle never fails.

“Would you want me more if I lost some weight?”

“Jesus, Russell,” she says, turning away from me, pulling the comforter tighter around her.

I never ask Sam what she does after I leave each morning, but my working assumption is that once I kiss her on the head she drifts gently back to sleep for at least another hour.

The F-train is crowded, but there’s a middle seat no one wants: an orange sliver between two passengers whose ass sizes exceed the MTA space allowance. I wedge myself between them and pull my newspapers from my messenger bag. It’s a small gesture. But whenever I’m surrounded by iPod listeners, BlackBerry users, Sudoku addicts and anyone looking to either shake me down or inspire my religious conversion, I immerse myself in a newspaper. Not just to create a barrier between me and my fellow commuters. Not just to fly the flag for the company that employs me. I happen to think a newspaper is a convenient, wireless, handheld device. On a good day it might even tell me something I don’t already know.

I conceal my

New York Times

inside the first section of the

Daily Business Chronicle

and start reading. It’s my way of reminding any media planners who might get on the train that the

Chronicle

still exists, even if its readership among the under-forty crowd is in sharp decline.

The news is all bad. Our future’s in the hands of scoundrels and fanatics. I skim the headlines, searching in vain for signs of hope for subway riders, New York City dwellers, American citizens at home and abroad, the entire God-fearing Christian world, people of all religions, agnostics, atheists, the planet we all must share. I read about the rescue effort underway halfway up an Oregon mountain. Three overconfident climbers are stranded. They ignored the weather forecasts and now about twenty people have to risk their own lives trying to save them. I imagine myself as a rescue worker, being lowered from a helicopter, buffeted by chill winds in the blinding snow. I can’t resist the urge to slap the face of the first man I reach: “Fuck you, you stupid fuck!” I scream. “Look at all the trouble you’ve caused. I could be at home in my mountain lodge right now. Relaxing with a nice hot chocolate. Feeding my faithful St. Bernard. Tiptoeing around my gorgeous but indifferent wife.”

I fold the paper and reflect for a while. I’m not sure what motivates mountain climbers anymore. It’s either heroism or idiocy or both. It’s not as if the mountains haven’t been conquered before. And we already have all the business metaphors we need.

Three years ago, when my company still spent money on such things, Jack Tennant, our division’s president, hired a mountaineer to talk to us about “Peak Performance.” Her claim to fame was that she was the first one-armed woman to climb Mount Everest.

She stood alone on the stage of our company’s auditorium talking about the teamwork required for such a complex expedition. She paced backwards and forwards against a backdrop of projected images from the climb. She told us all about the planning, the preparation, the different kinds of expertise required to achieve the ultimate goal. Until she held it up, it was impossible to tell which was her artificial hand. Reaching base camp was relatively easy, she said. The gang was all there. Tents were set up. You had plenty of supplies—food, clothing, medical equipment. But when the time came, she, the leader of the expedition, said good-bye to the team and, with only a trusty Sherpa to carry her camera and flag, set out alone for the final push.

“Aim high,” she said as her final, twelve-foot-tall image was projected on the auditorium screen. “Reach for the top. Dream big dreams. Set yourself unattainable goals. Because with teamwork you can transform the unattainable into the achievable.” After her speech we clapped enthusiastically and then lined up as she signed leftover copies of her once best-selling book. We weren’t expected to read it, but I did spend ten minutes looking at the pictures. There were three pages devoted to the surgeries, rehabilitation and technological advances that made her arm so functional. But I wanted to see what the Sherpa looked like. The only place I could find him, he was partially obscured in a group shot.

I emerge from a side exit at my midtown subway stop, and as I wait for the light to change, I raise my eyes to study the impressive high-rise building where I work. People still call it the Burke-Hart Building, even though Burke-Hart Publishing—the company that founded the

Daily Business Chronicle

—is now only a small division within the Ghosh Corporation.