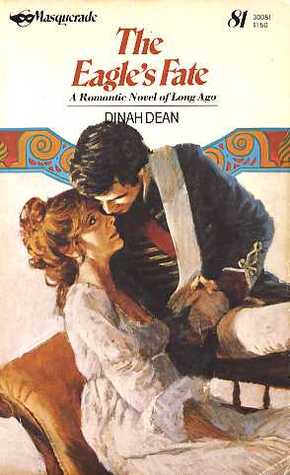

Russian series 03 - The Eagle's Fate

Read Russian series 03 - The Eagle's Fate Online

Authors: Dinah Dean

Font Arial impact roman arial black Verdana Georgia Palatino times Font Color black brown orange silver blue green teal antiquewhite red yellow white Font Size 12 14 18 24 28 32 38 42 Background Color white wheat lightgrey antiquewhite teal sienna tan beige navajowhite brown light blue burlywood silver gray black

THE EAGLE’S FATE

By

Dinah Dean

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

THE EAGLE’S FATE

The eagle’s fate and mine are one,

Which on the shaft that made him die

Espied a feather of his own

Wherewith he wont to soar on high.

Edmund Waller 1605-87

Chapter One

The weather had been beautiful all the past week. The air was bright and clear, with the slight pungency of early autumn, and the sun shone warmly all day long. The sweeping curves of the river were brilliantly silver, and Moscow shone like a fairy-tale city, jeweled with the gilded or coloured domes of its many churches. Even the old wooden houses in the poorer districts had acquired a charming greenish patina, transforming their customary drabness so that one looked twice at them, and saw how they might have been when they were new.

The bells chimed sonorously from a hundred towers for Sunday morning service on this first day of September, but the slowly-moving throngs in the streets passed the churches unheedingly, moving with the determination of migrating ants across the city, over the rivers and out through the gates into the countryside, north, east, south—anywhere but westwards.

One sunbeam penetrated the small window of a room on the upper floor of a shabby old house in the White City, north-west of the Kremlin, and lit up a pair of patched walking-shoes and the kneeling figure of Nadya Serova, pulling tight the last know in the rope around her father’s old traveling-trunk. She straightened up and looked about the room. The familiar, shabby furniture looked odd without any small, portable objects about, and there was nothing left now that could possibly be packed. Her eyes lighted on the shoes, and she moved to a chair to put them on, biting her lip over the thinness of the soles and hoping she would not have to walk too far in them.

She folded her hands in her lap, and again looked round the room. It was small and dark and sparsely furnished, and she could hardly regret leaving it, but it and the two even smaller bedrooms next door contained everything she possessed. However, if Luda managed to buy a horse and cart, it was hardly likely that it would be big enough to hold more than the two trunks which now contained all her clothes and portable belonging. Luda’s two or three bundles and their bag of food, so there was no more to be done but wait for Luda to return.

She had been gone for a long time now. Nadya got up and went to the window. If she leant out as far as possible, she could look along the narrow lane below to the wider street into which it led. The lane was deserted, except for a fat tabby cat which sat in a patch of sunlight amid the rubbish, placidly washing its face, but the stream of people passing along the main thoroughfare could be seen, and Nadya watched for a few minutes.

The cartloads of wounded soldiers were not so overwhelmingly numerous now, and neither were the carriages and waggons of the wealthier citizens. Now there were many more poor people, plodding along on foot, laden with bundles, towing frightened children, pushing or pulling their few possessions in decrepit handcarts, loaded beyond reason with all they owned. The more fortunate were driving carts dragged by worn-out nags, whole families perched on their worldly goods.

The noise was incessant, as it had been for several days now, ever since the first carloads of wounded soldiers from the battle at Borodino had passed through the city and the great exodus of Muscovites had begun. The creaking and rumbling of carts mingled with the sound of feet and voices, merging into a strange, frightening roar, and the bells still sounded above and beyond with their message of peace in a world full of fear and violence.

The noise suddenly changed subtly as a steady tramping joined in, and Nadya saw a body of soldiers cross her narrow field of view. These were not wounded men, but active infantry, marching in ordered ranks behind their colours, their familiar dark green uniforms grey with dust. She caught her breath as she realised that this could mean that rumours were true—the Russian Army was in retreat—and surely, if they meant to defend Moscow, they would not be marching on steadily through the eastern half of the city?

As she watched, file after file passed the end of the lane—half a regiment at least—and they were followed by a troop of artillery, the cannon rumbling deafeningly over the uneven roadway.

The river of people had split into separate currents to allow the soldiers to take the middle of the road, and the civilians were crowded to the sides, their movement slowing in the restricted space and causing them to crowd dangerously close together. People on foot were pushing, and the drivers of vehicles were forcing their way through, regardless of other people’s safety. Two carts locked wheels and stemmed the flow for a few minutes, and an eddy of pedestrians surged in and out of the mouth of the lane to get past. One figure detached itself from the crowd and came up the lane towards Nadya—a stout peasant woman in a rusty black dress, with a bright blue shawl over her had and shoulders. It was Luda, and she was alone and on foot.

Nadya hastened downstairs to let her in, a rat scurrying ahead of her and disappearing into the shadows of the dark vestibule. The grocer and his family, who owned and occupied the house apart from the three rooms which Nadya rented, had left two days before, without a word to Nadya or Luda, let alone an invitation to go with them. Nadya had made a few shy attempts to speak in a friendly fashion to them from time to time, but the difference in rant had been to great, and they had made no response, continuing to address her as ‘Princess’ with an obsequious politeness which, in the wife’s case, barely concealed a sneering contempt for the rich aristocrat so come down in the world that she must lodge in a grocer’s house with only one servant, and wear shabby clothes.

The house was strangely quiet, and Nadya’s footsteps echoed through the empty rooms as she ran down the creaking wooden stairs and pulled back the heavy bolts on the door. Luda pushed her way in impatiently and slammed the door shut behind her, hastening to bolt it again before she spoke.

‘What happened?’ Nadya asked. ‘Couldn’t you get a cart?’

‘Not a hope, Nadya Igorovna!’ Luda replied, her plump face creased with anxiety and anger. ‘You wouldn’t credit the

greed

…..! They’re asking as much as

five hundred roubles

for a broken down cart and a toothless old nag! And getting it too! I don’t know what’s wrong with everyone—it’s as if the Devil’s loose! Everybody’s leaving the city as fast as they can go, pushing and trampling to get away—they say the French’ll be here tomorrow! What’s to become of us all? Holy Mother protect us!’

She crossed herself, and then suddenly became business-like, thrust her hand into the pocket of her voluminous skirt and pulled out a small clinking bag. ‘Here—the fifty roubles you gave me to get the cart with—you’ll not get anything of the sort for it, so you’d best put it somewhere safe, for everyone’s out for themselves now! It’s a good thing you got gold—paper money’s worth nothing!’

‘What are we going to do?’ Nadya whispered.

‘I don’t know. Stay here and hope for the best?’ Luda replied uncertainly.

There was silence for a few moments. A mirror, forgotten by the grocer’s family in their haste and still hanging on the wall, cast a little more light in the dark vestibule by the door. Nadya was reflected in its dull surface like a dim ghost—a slender, fairly tall young lady with a pale oval face, a straight nose and pale blue eyes below curving dark eyebrows. Luda looked from the reflection to the living girl and sighed, remembering the old days when the light brown hair had been elaborately curled and decked with flowers, the too-firm mouth had been relaxed and smiling, and there had been no little worried crease between the dark brows.

‘We shall have to walk,’ Nadya said, having considered the matter.

‘Walk!’ Luda exclaimed, horrified. ‘But you said we’d go to Ryazan, and that’s nearly a hundred and fifty

versts

! (1

verst

=2/3 mile) We can’t walk so far! Better stay here and pray, Nadya Igorovna.’

‘Rubbish!’ Nadya replied briskly, firmly leading the way upstairs. Luda followed, puffing and voicing objections, which gradually died to a mutter as she ran out of breath.

Back in her own rooms, Nadya hastily unroped the trunks and pulled out the most precious of her smaller possessions. They were few enough—a pair of miniatures of her parents, her four remaining pieces of jewellery, an ivory-backed hair-brush and mirror, and her little icon. They fitted easily into a small valise, and she wondered what else she should take. She considered the contents of the heavy iron box in which her father had kept his papers, but concluded that there was nothing very important among them, and instead, crammed in a change of underclothing and stocking. Meanwhile, Luda had recovered her breath and was still expostulating.

‘We can’t walk to Ryazan!’ she insisted. ‘Why there, anyway?’

‘Because my friend, Countess Kalinskaya, lives near there,’ Nadya replied as she closed and locked the valise.

‘But you haven’t seen her for—what?—five years!’

‘We’ve exchanged letters.’

‘What make you think she’ll take us in?’

‘She was my best friend at school. In any case, there’s no one else I can go to.’ Nadya put a handful of low-value coins in a stocking-purse and pushed it to the bottom of her reticule, then lifted her skirts and firmly pinned the bag with her fifty gold roubles to her light corset with a securely fastened brooch. It made a heavy, uncomfortable lump, but at least it could not easily be stolen from her, and a critical inspection in the mirror showed that the skirts of her high-waisted dress concealed it well enough. The dress was a sober dark gray stuff one, four years old but serviceable, if dull and unbecoming.

She found another brooch and added it to the fastening of the bag, to be more certain. It contained all the money she possessed until the next payment of her annuity fell due in three months’ time, and goodness knew when she might be able to get possession of that!

‘You’d better stay here.’ Luda was whining a little now, her face screwed up like a petulant baby’s and her little black eyes almost invisible.

Nadya’s patience expired at last, and she turned on the old woman.

‘Ludmilla Matveyevna!’ she began in a firm, quiet tone. Luda looked apprehensive as soon as the formal address was spoken. ‘I am still mistress here, and

I

decide what I shall do! I have no intention of being here when Bonaparte and his brigands enter this city, and any female with the slightest grain of sense would say the same! However, I shall not order you to come with me. You are no longer a serf, and if you prefer to stay here, than you may do so, but don’t say another word to me about it!’