Sacred Trash (16 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

In 1910, while looking through some of the Geniza manuscripts that Schechter had brought with him from Cambridge, Davidson happened on a seemingly trivial item. It consisted of two 5 × 4–inch pages containing instructions in Judeo-Arabic regarding the procedure of a prayer service. Of particular interest to the no-longer-fledgling scholar was the fact that the directions cited the first words of several liturgical poems, or

piyyutim

(the Hebrew term derives from the Greek

poeites,

meaning “maker,” as in the archaic English word for “poet”). The hymns had been written by a legendary if obscure Hebrew liturgical poet (

payyetan

) named Yannai, about whom almost nothing was known and whose extant work, for much of the previous millennium, had amounted to a single serial composition, part of which found its way into the Passover Haggada in some Jewish communities. The instructions also explicitly stated that the poems came from a complete liturgical collection

—Mahzor Yannai,

or Yannai’s “cycle” of hymns for the liturgical year—and they implied that these hymns were extremely popular: only the first lines of the poems were listed, as the manual writer assumed that his readers had the work in hand. The manuscript also mentioned melodies and refrains.

Yannai’s name barely appears in medieval Hebrew literature. In the early tenth century, Saadia Gaon counts him among the “elder poets,” whose verses he says are model compositions. And the name is made nearly immortal when the German-Jewish liturgical poet and commentator Ephraim of Bonn (1133–after 1196) tells the story of how a certain hymn by Yannai is

not

recited because—in an act of what the Talmud in another context calls

kinat soferim,

or writer’s envy—he murdered his student Eleazar Kallir, the most prolific and celebrated of the early Hebrew liturgical poets, by placing a scorpion in his sandal! “May God forgive all those who say this of Yannai,” the only quasi-compunctious Ephraim adds, “if it did not really happen.”

Nor was Yannai much of a presence in the modern scholarly literature

available to Davidson. One early-nineteenth-century writer thought he lived in Italy in the tenth century; later evidence had moved his date back to the mid- or early seventh century. In 1901 the pathbreaking Shelomo Wertheimer published two short compositions by the poet from among his Geniza purchases. And that was the sum total of what was known.

So the skimpy manuscript pages that Davidson had found were quite valuable, and he published them along with his commentary in the principal professional journal of the day, the

Jewish Quarterly Review.

Beyond that, however, he could go no further, and there once again the matter stood.

We don’t know precisely what happened next, but one can imagine that this find would have set the wheels whirring in the mind of the unpretentious yet ambitious Hebraicist. Davidson’s wife, in her much later memoir, notes that after her husband had brought out his important edition of

The Book of Delight,

a picaresque volume by the twelfth-century Spanish Hebrew poet Yosef ibn Zabara, “the urge became ever stronger to go abroad and seek manuscripts at their source.” Like Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, Davidson wanted to see the real thing, not a reproduction, and he was especially interested in inspecting the enormous collection of Geniza documents that Schechter had left behind at the Cambridge University Library. And so, in June of 1914, having booked passage on a freighter with the help of a friend, Davidson, his wife, and their young daughter set out on a twelve-day voyage to reach Europe.

Davidson did make one important discovery in Cambridge, of another work by Saadia Gaon, but it was after he returned from England that “the modest man … [with] a veritable genius for labor,” as one colleague described him, found what it seems he’d been looking for. Again, we don’t know when, or even how—neither he nor his wife has left a paper trail to his epiphany, and much of his eight-thousand-volume library, which was housed at JTS, was destroyed in the 1966 fire there—

but at some point (institutional lore has it on one Sabbath afternoon, waiting for students to arrive for tea), something or someone told Davidson to take the Burkitt and Taylor palimpsest volumes down from the shelf and have another look at that Hebrew upper writing, which Schechter had identified as liturgical and which Charles Taylor had gestured at in passing as he hurried on to the more alluring, underwritten Greek.

And there it was, and had been for nearly twenty years, in at least

four places

on several pages bound between covers, printed by the Cambridge University Press and distributed to libraries around the world, where no one had noticed: Yannai’s name, in that bold and easily decipherable Hebrew hand, running down the spine of a poem as an acrostic “signature.” It was a find that would, in time, lead scholars to the complete works of one of the titans of Hebrew poetry and a thorough reconsideration of the evolution and nature of Hebrew literature.

Given the significance of Davidson’s discovery, one can’t help but note what has been called the “grotesque” nature of the fact that these hymns had been lying there, available in print for two decades. Yannai’s work appeared on eight of the seventeen palimpsest pages published by Burkitt and Taylor—without anyone noticing what it actually was. The palimpsestic ironies within the grotesquery of that long delay in discovering the Yannai are compounded further when one realizes that Burkitt’s terse report of his accidental Aquila discovery was printed in the

Times

of London on Tuesday, August 3, 1897,

directly under

Schechter’s spectacular announcement of having found “a hoard of Hebrew manuscripts.” Adding to that irony was part two of Schechter’s article, which was published the following year and went on at great length about the nature of the early medieval Hebrew hymns and the pleasure their co-redeemer took in them. “I am particularly fond,” writes Schechter,

of looking at the remnants of a Piyyutim collection … with their rough edges and very ancient writing. In turning those leaves, with

which time has dealt so harshly, one almost imagines one sees again the “gods ascending out of the earth,” transporting us, as they do to the Kaliric period, and perhaps even earlier, when synagogues were set on fire by the angels who came to listen to the service of the holy singers, and mortals stormed Heaven with their prayers.… These are, however, merely my personal sentiments. The majority of students would look rather askance upon the contents of the Sabbatical hymn under which the remains of Aquila were buried for nearly nine centuries.

Already in 1897, then, Schechter realized that he had before him (and over the Aquila) a liturgical hymn for the Sabbath that was very likely from the period of Yannai’s famous student and reputed victim, Kallir, and he even grew rhapsodic over the transformational quality of the presence of these poems on the ancient page. And yet, inexplicably, Schechter never seems to have directed his protégé, Israel Davidson, whose field this was, to examine these works—not even after the latter’s 1910 article about Yannai, which was followed by a series of pieces published over the next three years under the same heading, “Poetic Fragments from the Cairo Geniza” (all in a journal that Schechter himself

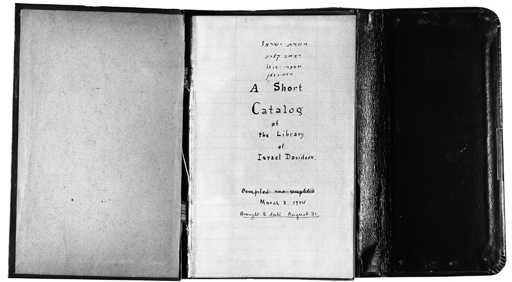

coedited). Nor did Davidson’s 1914 cut-rate cruise to Cambridge produce anything in the way of a lead. Furthermore, Davidson’s handwritten catalog of his private library—two highly evocative palm-sized notebooks encased in red wraparound leather, prepared in 1914 and titled

Hemdat Yisrael,

Hebrew for “Israel’s Delight” (or “Desire”), shows that he owned at least one of the Cambridge palimpsest volumes, and so would have known of the other. “If the two English scholars [Burkitt and Taylor] had not published the facsimiles,” Davidson noted, “the Mahzor of Yannai would very likely have remained unknown for many more years to come.”

N

ewly oriented, Davidson went back to the palimpsests and identified forty individual units of eight long composite poems, all of which were clearly part of that Yannai “hymn book” he’d written of in 1910. Each of the elaborately orchestrated sequences was intended to accompany the portion of the Torah as it was read in Palestinian synagogues on the Sabbath during the period of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. As such, these poems were front and center in the calendrical and spiritual consciousness of that community’s Jews, who would, weekly, at the core of their sacred service, await the latest word from their poet—news that might inject life into their faith. In their serial and commissioned aspect, Yannai’s composition of poems for the prayer service has been compared to Bach’s production of cantatas for Sunday after Sunday while serving as musical director of the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig.

Differing from present-day Jewish practice, which is based on the Babylonian rite and completes the cycle of reading through the Torah annually, Palestinian communities in the Land of Israel and the Diaspora divided the Torah into much shorter portions and so they took three times as long to read from Genesis to the end of Deuteronomy before

starting all over again. This “triennial” division of the Five Books of Moses, along with the distinctive Palestinian spelling of the poet’s name (

yod, nun, yod, yod—

rather than

yod, nun, alef, yod—

though both were pronounced ya-

NIGH

), and the fact that there were no references in the poetry whatsoever to Islamic presence in the Holy Land, confirmed previous speculation that the poet hailed not from Italy, and certainly not from the tenth century, but from Palestine prior to the seventh-century Muslim conquest of the region.

Looking from the other end of the telescope for the work’s earliest possible date, we see both that the poet makes extensive use of particular collections of midrash that were edited in the late fifth century

C.E

. and that his hymn book assumes the existence of a standardized, if still flexible, core liturgy, which was established shortly before that. This leads most scholars to date the poet to the mid-to-late sixth or early seventh century, which is to say, around the reign of Justinian the Great and the height of Byzantine achievement and influence, when architectural monuments such as the Ravenna mosaics were being marveled at and the rebuilt Hagia Sophia was worshipped in. It is also when the preeminent Byzantine hymnist of the jeweled style, Romanos, was writing his ornate, theatrical poems.

But just as the triennial system contributed to the development of Hebrew liturgical poetry—in that the brevity of the weekly readings left much more time for embellishment and literary commentary in the form of hymns and midrashim—it was also responsible for the tradition’s demise. For one, the proliferation of liturgical poems eventually provoked widespread rabbinical opposition to the phenomenon itself, and, increasingly, pressure was put on communities to rid their worship of these overgrown baubles. More significantly, when the triennial reading fell out of practice—by the ninth or tenth century in Palestine and, it seems, early in the thirteenth century in Fustat—Yannai’s hymns and others like them were rendered obsolete or fundamentally distorted in

attempts to dismantle them and adapt them to the annual (Babylonian) reading. As a result, they disappeared almost entirely.

Now that work was back, at least in part—though what it was saying was by no means clear, as one example of many makes plain:

[when any man hath an issue] out of his fle[sh] and …

A

s who [ ........ ] on high .................

[

B

....... ] turn [ ................. ]

C

ircumscribed by justice as well..........

[

D

..... ] as an issue of .........

E

ach who [ ............... ] made him

F

or his desire....... if ... it [..... ]

[

G

] ... of his from him, and his law and ma[ ... ]

[

H

] ...............................

I

mpurity lies within him, if his ethic ends

J

...... upon him his corrector