Sagaria (14 page)

Authors: John Dahlgren

Sagandran tried not to laugh. The pickets were hardly larger than toothpicks. Even a squirrel or a rabbit might trample them underfoot without noticing. Sobering, he realized that squirrels and rabbits must be terrifyingly huge creatures to his new acquaintance.

“I’ll help you rebuild it,” he said, but his mind was on something else he’d noticed. Almost concealed under the shade of an overhanging bush was a miniature house, perfect in every detail down to the overlapping orange-brown tiles on its roof. A little curl of smoke was coming out of its diminutive chimney.

“Oh, all right,” said Flip with sudden eagerness.

“Is that your home?” Sagandran asked as he squatted down and began looking around for twigs the right size to be fence posts.

“Yes, it is.”

Flip was grunting from the weight as he lifted one of the pickets Sagandran had knocked over. It hadn’t occurred to Sagandran that something he thought

was as light as a feather might be quite heavy for a creature as small as Flip.

“But only for the past few weeks,” added the adventurer, resignedly deciding that the fence post was too damaged to be reused and starting to haul it off toward a woodpile by the side of his cottage. “I was brought here from my home a very long way away.”

He related his story to Sagandran as they worked. Flip came from a village called Mishmash that was “somewhere on the far side of the mountains.” Flip didn’t say which mountains these were, but the closest mountains Sagandran had noticed while he was descending toward the forest had been many tens of miles distant. Even if Mishmash was tucked away in a valley in that nearest range, Flip was, indeed, a long way from home. Flip’s tale was one of being snatched up by a hawk that was partly trained by an acquaintance of his called Old Cobb. The bird’s training had stopped it from devouring him or taking him home to its nest and feeding him to its chicks, but the untrained part hadn’t been able to work out what it was supposed to do with him, so after a long and frightening flight, it had unceremoniously dumped him in this forest. Far from his own kind and, in particular, far from someone called Jinnia (whom Sagandran gleaned was a big lady mouse of ravishing loveliness and whose name kept popping up in the story at unexpected moments), Flip had eventually settled down here. He’d constructed a new home from scratch and Sagandran was rightly impressed. He wouldn’t have known where to start building a house on a human scale.

Squinting more closely at the cottage, he saw that the tiles on its roof were the lozenges from pine cones; that its walls were made from flattened bark; and that its chimney was assembled from broken sheets of slate, the corners chipped so accurately and jammed together so firmly that there was hardly a leak. The only task that seemed to have defeated Flip was finding something he could use as glass for the windows; they were just open rectangles. Sagandran thought about offering his little friend the clear plastic from the head of his flashlight, but decided he’d better keep his flashlight intact in case he needed it further along the road.

In return, Sagandran told of how he’d come here – Flip punctuating the account with frequent exclamations of, “well, I never,” and “good heavens.” When he came to the part about dropping like a stone from high above the clouds with only a cylinder of blue light to support him, Sagandran thought his new friend was going to faint. Luckily, they’d finished rebuilding the fence by then, so Flip simply sat down and breathed very hard for a while.

The repaired fence looked almost better than the old one, Sagandran thought, and he congratulated himself silently. He’d found a piece of bark among the

pathside debris, and as he talked he clipped it with his fingernails to make a gate. What to do about hinges for the gate was beyond him, especially since the hinges would have to be so very tiny, but he assumed that Flip would be able to work that one out.

“So you’re a type of monster called a ‘hue man,’” said his mousy friend at last. “You’re obviously not a worg, because worgs are even uglier than you are. That’s why I warned you not to follow the road to Bolster’s house. He’s a worg of the worst possible kind.”

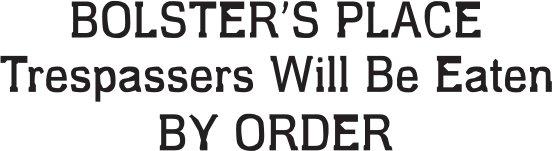

Bridling a little at the “even uglier” remark, Sagandran elicited from the little fellow that in fact he’d only ever seen two worgs: Bolster and one other, and that the other had been at a distance that Flip had been in the process of rapidly increasing. Even so, from the gasped descriptions, it was evident that worgs were indeed worth avoiding at all costs. Urged by Flip, Sagandran trotted over to examine the sign more carefully, and he saw that he hadn’t read the whole of it. What it said in full was:

He gulped. From what Flip had told him, worgs were twice as tall, twice as wide, twice as warty, twice as vicious and twice as revolting to look at as Sagandran.

“Thank you,” he said simply as he returned to kneeling beside the cottage and its fence.

Flip looked smug. “Always read the small print, that’s what I say.”

During Sagandran’s brief absence, Flip had produced a couple of mugs from somewhere that were smaller than thimbles, and he offered one to Sagandran. “Tea?”

Lifting the mug to his lips, Sagandran saw that it was the cup of an acorn, the bottom of it carefully chewed away to make a flat surface. It held so little liquid that he could hardly taste the tea as he tossed it back, but there was just enough of the hot fluid to make him realize he was thirsty.

“Is there a stream anywhere near?” he asked Flip.

“Yes. Can’t you hear it?”

Listening intently, Sagandran could just hear the sound of tumbling water. If he’d heard it before he would have assumed it was just a breeze disturbing the leaves.

“It’s over that way,” Flip informed him, pointing.

Sagandran tramped through the forest until he found a bright little brook

babbling between grassy banks. Its waters were so clear that he had no trouble seeing the mud and pebbles on the bottom, and the tiny fish and tadpoles that darted between them. He lay down on his stomach by the water’s edge and plunged his face right in, drinking long, cold delicious drafts and hoping he wouldn’t swallow a tadpole in one of them.

When he got back to the cottage, there was no sign of Flip. The plume of smoke was absent from the chimney; Flip must have doused the fire.

Sagandran looked around agitatedly. Had the little fellow changed his mind about his human acquaintance and fled off into the woods?

Then Sagandran heard two things.

The first was a loud, piggish grunt. It seemed to come from somewhere up the path to Bolster’s Place.

The second was a hiss. “Psssssst.”

He cast about for the source of the hiss.

The pink tip of Flip’s nose could just be seen peeping out from beneath a large fallen leaf some three or four yards away from the trail.

“Psssssst,” Flip said again.

“I hear you,” whispered Sagandran. What he also heard, coming from the same direction as the grunt, was the sound of heavy footfalls.

“Hide,” said Flip urgently. “It’s Bolster.”

Sagandran didn’t need a second telling. One of the trees nearby had long, drooping branches like a weeping willow, though its foliage was like big bronze coins. He darted under the curtain of the leaves. And not a moment too soon.

Round the bend puffed one of the ugliest monstrosities Sagandran had ever clapped eyes on. It wasn’t twice as tall as he was, as Flip had claimed, but it was at least three times beefier, which more than made up for its height. Its skin was the color of putrescent pond scum and covered in big, misshapen protuberances that looked like festering boils. The overall shape was roughly that of a man, which made the creature even more revolting. It had two arms, two legs and a head, but all the proportions were hideously wrong. There was no neck; the head was so low-set that the face seemed to be almost in the creature’s chest. The mouth had more teeth than a saw mill, and silvery-green drool dribbled from both ends. The two piggy, small eyes reminded Sagandran of trodden on bugs. The feet were like sides of meat and the bowed legs likewise. The monster’s right arm was a little longer and substantially more muscular than its left, and it clutched a club of knotted wood, the thicker end of which was thicker than Sagandran’s waist. The monster’s head was bald except for one perfectly sculpted coil of greasy black hair. Its hands were like overweight squids.

Flip had said that Bolster (Sagandran assumed this was Bolster) was a worg.

Peering through the spaces between the hanging branches, Sagandran would have described the creature as a troll. That trolls and worgs were at least closely related was partially confirmed by Bolster’s vaunted habit of eating people. That’s what trolls did. Sagandran knew – he’d read enough of the right books.

Bolster came to a halt at the fork in the road and looked around, his slug-like eyebrows beetling above those vindictive, little red eyes.

“I can smell a … a hooman,” Bolster said in a voice like greasy water gurgling down a plug hole.

The worg hefted its bludgeon aggressively and stared at Sagandran’s tree.

“I tink it’s …

dere

.”

As the worg leadenly advanced toward the clearly quite useless hiding place, Sagandran found himself rooted to the spot. All he could do was sweat in terror, and he didn’t think he was doing even that particularly well. So much for his dreams of being a hero, of rescuing Grandpa from villainy and saving the world of Sagaria from the powers of evil. He was going to end up being somebody’s afternoon tea.

Unless …

The worg parted the branches, looked through them and belched. Sagandran thought he was going to die from the cloud of noxious gas. Which would be a bit of a shame, because he was – he thought – securely hidden once again, having managed to will some movement from his feet at the last moment and dash around the other side of the tree trunk. He devoted the remainder of his mental energies to trying to stop his teeth from chattering too loudly.

“I can see you, little hooman,” announced Bolster. “Your elbow’s stickin’ out. I’m not entirely stoopid, you know.”

So much for Sagandran’s brilliant scheme.

“We can do dis da easy way or da hard way,” the worg continued. “Da easy way is dat I kill you before I start eating you.”

He didn’t have to spell out the hard way. Sagandran could imagine it only too well. He came out from behind the trunk and confronted the worg directly. Any hope he might have that Bolster would look better close up were dashed.

“I strongly advise you not to eat me,” he said, doing his best to control his voice, which seemed to want to imitate a quartet of piccolos.

Bolster slapped the club into his left hand a couple of times, thoughtfully.

“Why’s dat?”

“I’m full of proteins. And lipids.”

“Eh?”

“Not to mention free radicals, cholesterol and saturated fats.”

“Eh?”

Sagandran waved his hand airily. “All of them are real dietary no-nos,” he explained. “They play havoc with the digestive system, you see. Everybody knows that.”

The worg seemed unconvinced. Clearly he hadn’t known that.

“Dem free wotsits,” he said. “Dey sound real tasty to me.”

“Oh, they

taste

all right,” agreed Sagandran, racking his mind to try to remember what it was that free radicals did to you. All he knew was that he’d read in one of Mom’s books that you were best to avoid them as much as possible, but he couldn’t recall why. On the other hand, Bolster had obviously never heard of them at all, so the worg wouldn’t be able to tell if Sagandran had improvised.

“They’re the most potent of all carcinogens.”

Bolster’s gaze wavered not at all.

Sagandran silently cursed himself for using another word the worg didn’t know the meaning of.

“They make bits of you start dropping off,” he expanded, casting around wildly for other disgusting lies he could tell about free radicals.

“Tings drop off me all da time,” said Bolster, unimpressed. “I jus’ grow new ones.”

“And they make you repulsive to wom—er, members of the opposite sex.”

Bolster gave him a broad grin. Sagandran was reminded of the front row of an advancing Roman legion. “Dat’s da way we worgs like it.”

“And they” – he took a stab in the dark – “cure boils!”

There was a reaction from Bolster at last. The big ugly face looked appalled. Sagandran hadn’t realized that it could be so expressive.

“Den you’s right, I better not eat you.”

Sagandran relaxed against the trunk of the willow-type tree and let out a big puff of gratitude.

“But I can still have all da fun of cudgelling you to death and grinding your head up into paste,” ruminated the worg.

Yikes!

“Er, I’d not do that either if I were you, Mr. Worg.” The chamber group of piccolo players had expanded to at least an octet, and they were all trying to play different tunes.

“Huh?”

“Do you know what there is in the brains of a growing human boy?”

“Pink stuff, mostly.”

“That pink stuff, as you call it, is loaded with incredible concentrations of nitroglycerine. It’s the free radicals that manufacture it – biochemistry one-oh-one. And a waste product of the reaction is trinitrotoluene; that’s TNT to you and me.”