Salsa Stories (3 page)

Authors: Lulu Delacre

Back

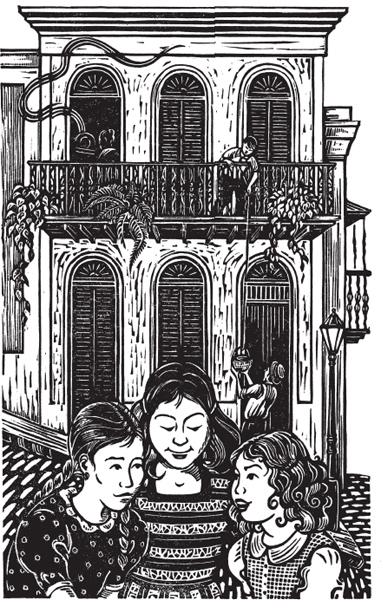

in the 1940s, in Puerto Rico's walled city of Old San Juan, everybody knew everybody else. We neighborhood children played freely together on the narrow streets, while from windows and balconies adults kept a watchful eye on us. It was only my lonely friend José Manuel who was forbidden from joining us.

“Look, Evelyn,” whispered Amalia. “He's up there again, watching us play.”

Aitza and I looked up. There he was, sitting on his balcony floor. He peered sadly down at us through the wrought iron railing, while his grandma's soap opera blared from the radio inside. No matter how hard José Manuel tried, he could not convince his grandma to let him play out on the street.

“Too many crazy drivers! Too hard, the cobblestones!

¡Muy peligroso!

” His grandma would shake her head and say, “Too dangerous!”

Besides her fear of danger on the street, José Manuel's grandma kept to herself and never smiled, so most of us

were afraid of her. That is, until my sisters and I changed all that.

One day, Amalia suddenly announced, “I'm going to ask his grandma to let him come down and play.” If anyone would have the courage to do that, it was my little sister Amalia. Even though she was only seven, she was the most daring of the three of us.

We never knew what she would do next. In fact, at that very moment I could see a mischievous grin spreading across her freckled face as two elegant women turned the corner of Calle Sol. Once they strolled down the street in front of us, Amalia swiftly snuck up behind them and flipped their skirts up to expose their lace-trimmed slips.

“¡Sinvergüenza!”

the women cried out. “Little rascal!”

We could hardly hold our laughter in. We all looked up to make sure none of the neighbors had seen her. If anyone had, we would surely have been scolded as soon as we got home. News traveled fast in our neighborhood.

Luckily, only José Manuel was watching us with amusement in his wistful eyes. Grateful for an audience, Amalia smiled at him, curtsied, and ran down the street toward the old cathedral with us chasing after

her. I couldn't help but feel sorry for my friend as we left him behind.

There was hardly any sea breeze that day, and running in the humidity made us quite hot.

“Let's get some coconut sherbet,” said Amalia, peeling her damp red curls away from her sweaty neck.

“¡SÃ, sÃ,”

we agreed, and we chattered excitedly about our plans for that night all the way to the ice-cream vendor's wooden cart by the harbor.

It was June twenty-third, and that night was the Night of San Juan. For this holiday, the tradition was to go to the beach, and at exactly midnight, everyone would walk backward into the sea. People say that doing this three times on the Night of San Juan brings good luck. I thought of my friend José Manuel. Perhaps if he did this with us, his luck would change, and his grandma would allow him to play with us outside on the street.

I thought about this as we bought our coconut sherbet and then ate it perched on the knobby roots of the ancient tree above the port. Excitement stirred in me while the distant ships disappeared over the horizon.

“How can we get José Manuel to go to the beach tonight?” I asked my sisters.

“Evelyn, you know very well his grandma will never let him go,” Aitza said. “You know what she will say â”

“¡Muy peligroso!”

Aitza and Amalia teased at once. “Too dangerous!”

Â

It was getting close to dinnertime, and we knew we had to be home soon if we wanted our parents to take us to the beach that night. So we took the shortcut back across the main square. In the plaza, groups of men played dominoes while the women sat by the fountain and gossiped. Back on the street we heard the vegetable vendor chanting:

“¡Vendo yucca, plátanos, tomates!”

He came around every evening to sell his fresh cassava, plantains, tomatoes, and other fruits and vegetables.

Leaning from her balcony, a big woman lowered a basket that was tied by a cord to the rail. In it was the money that the vendor replaced with two green plantains. As we approached our street I saw José Manuel and his grandma out on the second floor. She gave José Manuel money and went back inside. He was about to lower his basket when I had an idea. Maybe there was a way we could ask him to join us.

“What if we send José Manuel a note in his grandma's basket inviting him to go to the beach with us tonight?” I offered.

“It will never work,” Aitza said. “His grandma will not like it. We could get into trouble.”

“Then we could ask her personally,” I said.

“But what excuse could we use to go up there?” said Aitza. “Nobody ever shows up uninivited at José Manuel's house.”

“Wait! I know what we can do,” Amalia said, jumping up and down. “We'll tell him to drop something. Then we'll go up to return it.”

Even though Aitza was very reluctant, we convinced her to try our plan. We wrote the note and asked the vegetable vendor to please place it in José Manuel's basket next to the vegetables. We impatiently waited on the corner as we watched. When he opened the note, he looked puzzled. He took the tomatoes he had purchased in to his grandmother. Soon he returned with his little red ball. He had just sat down to play when suddenly the ball fell from the balcony. It bounced several times, rolled down the hill, and bumped into a wall. Amalia flew after it. “I got it!” she called triumphantly, offering me her find.

With José Manuel's ball in my hand we climbed up the worn stairs of his pink apartment house. And while Aitza and I stood nervously outside his apartment trying to catch our breath, Amalia knocked loudly on

the wooden door. With a squeaking sound it slowly opened, and there stood José Manuel's grandma wearing a frown as grim as her black widow's dress.

“¿SÃ?”

she said. “How can I help you?”

Aitza and I looked at each other. She looked as afraid as I felt. But without hesitation, Amalia took the little ball from my hand and proudly showed it to José Manuel's grandma. I wanted to run, but a glimpse of José Manuel's hopeful expression made me stay.

“This belongs to José Manuel,” Amalia declared. “We came to return it.” Amalia took a deep breath, then took a step forward. “We also wanted to know if he could come to the beach tonight with our family.”

Aitza and I meekly stood behind Amalia.

“The beach?” José Manuel's grandma asked, surprised, as she took the little ball from Amalia's palm.

“Y-y-yes,” I stuttered. “Tonight is the Night of San Juan, and our parents take us to the beach every year.”

José Manuel's grandma scowled at us. How silly to think she would ever let him go. I suddenly felt embarrassed and turned to leave, pulling both sisters with me by their arms.

“Wait,” we heard her raspy voice behind us. “Come inside for a

surullito de maÃz

.”

It was then that I smelled the aroma of the corn fritters that was escaping from the kitchen. José Manuel's grandma was making

surullitos

for dinner.

“Oh, yes!” Amalia followed her in without a thought. And before we knew it, we were all seated in the living room rocking chairs next to José Manuel, eating the most delicious corn fritters that we dipped in garlicky sauce. Somehow, sitting there with José Manuel, his grandma seemed less scary. After we finished, José Manuel's grandma thanked us for our invitation and said she would let us know.

José Manuel smiled.

When we got home we found Mami waiting with her hands on her hips. She had just hung up the phone with José Manuel's grandma. She had reason to be upset. Not only were we late for supper, but in our excitement we had forgotten to ask for permission before inviting José Manuel to the beach. We all looked down, not knowing what to do or say.

“It wasn't my fault. It was Evelyn and Amalia's idea,” volunteered Aitza, the coward.

“

Bendito,

Mami,” I said. “Don't punish us, we forgot.”

“Forgot?” Mami asked.

“

SÃ,

Mami,” we all said at once. “We are sorry.”

“Actually it was very nice of you girls to invite

him,” said Mami. “But please remember to ask me first next time.”

Â

Late that night the whole family went to the beach as was our tradition on the Night of San Juan. But this time was special, for we had José Manuel with us.

The full moon shone against the velvet sky. The tide was high, and the beach swarmed with young revelers who, like us, had waited all year for this night's irresistible dip in the dark ocean. The moment we reached the water we all turned around, held hands, and jumped backward into the rushing waves. Amalia stumbled forward, Aitza joyfully splashed back, and so did I as I let go of my sister's hand. But my other hand remained tightly clasped to José Manuel's. When my friend and I took our third plunge into the sea, I wished good luck would come to him, and that from then on, his grandma would allow him to play with us out on the street. And as a wave lifted us high in the water, I suddenly knew this wish would come true.

I

used to be a sickly child those years long ago in Buenos Aires. Once I had a severe virus that left me unable to eat or drink any dairy foods for eighty-nine days. Eighty-nine long days. I know because I counted each one carefully on my calendar. And I couldn't have been more pleased the day my doctor assured me that I could have milk again. That meant that at teatime that afternoon I would be able to have

alfajores

. Those were my favorite sandwich cookies, the kind that were filled with milk caramel. All day at school I thought of nothing else, and couldn't wait to get home.

Finally, the dismissal bell rang loudly and snapped me out of my sweet daydream. I leaped up from my seat, and put on my blue wool coat and matching beret and gloves to protect me from the chilly weather. Buenos Aires is always chilly in July. For while half of the world is warmed by the summer sun, Argentina is gliding through winter.

“See you Monday, Susana!” I heard my schoolmates

call from behind me as I crossed the courtyard. I barely had time to turn around and wave good-bye to them before I cut into the wind and hurried home to my mother and Abuela Elena. Our apartment house was only two blocks away from school, but the more I rushed to get there, the further away it seemed. I was trying to get home before my twin brother, Oscar, even though I knew he would run home ahead of me. That way he could sneak into the kitchen and take inventory of the afternoon sweets. At eleven years old, I might have been taller â but he was, without a doubt, faster. Particularly when sweets were involved.

Today's afternoon tea,

la hora del té

, was a special one. Aunt Cecilia and Aunt Morena were coming to join us. Of course, teatime was delicious every day of the week. But it was especially delicious when we had company. Only then would Abuela Elena buy

alfajores de dulce de leche

. And today, after eight-nine days of deprivation, I would finally satisfy my craving. My mouth watered at the thought.

“Hola, querida,”

Abuela Elena greeted me, then took my coat and hung it next to Oscar's. He had, as I'd predicted, arrived before me. I washed my hands quickly and went to kiss my parents and aunts who had just sat down at the elegantly set table. After I took my place

next to Aunt Morena, Elvira appeared in her starched white cap and apron through the kitchen door, with a steaming silver pot of English tea.

“Leave it on the tea cart next to me, Elvira,” said Mamá.

As soon as Elvira went back to the kitchen, Mamá prepared each individual cup with experienced grace. I saw her lace the perfumed tea with thin ribbons of cold milk and spoonfuls of sugar while I craned my neck to peek at the plate of sweets behind the centerpiece. But the large bouquet of roses hid them well.

Mamá served the tea to Oscar and me last. Then, as always, she passed the plate of tea sandwiches around. After that, she passed around a plate filled with buttered toast. And when everyone had their fill of tea sandwiches and toast, it was finally time for the sweets.

As Mamá lifted the serving dish with tiny brioches and sweet scones, I saw the unimaginable. I looked again in case I had seen wrong. But I had not. In the middle of the sweets plate there was only one

alfajor!

Aunt Cecilia took the dish, chose a scone, and ceremoniously passed it on to Abuela who served herself a brioche. Neither of them touched the lone sandwich cookie. I could not take my eyes off of it. Papá took a

scone and handed me the rest. As I held the plate in my hands, time seemed to stop. My whole body ached for that

alfajor

. But one look at Mamá and it was clear I had no choice. Her silent gaze firmly warned me against improper manners at the table. I knew exactly what she was thinking:

Guests come first.

So reluctantly, I handed the plate to Aunt Morena. I knew she had a sweet tooth as big as mine, and I expected her to take what I had dreamed of eating for so long. But she didn't. Then, the plate had barely reached Oscar when the worst possible thing happened. With a single quick movement of his hand and a sneaky smile, Oscar raised the cookie to his lips â and gobbled it up!

I gave Mamá a stricken look.

“Elvira,” Mamá called behind her. “Bring more

alfajores, por favor

.”

But when Elvira returned from the kitchen, she was empty-handed. “Señora,” she whispered, “there are none left.”

I stared, dumbfounded.

“What?” asked Mamá. “Did you not buy half a dozen?”

“We bought the last four at the bakery,” said Abuela.

“That means there are three left!” I blurted out.

“They've disappeared, Niña Susana,” Elvira apologized. “I looked everywhere in the kitchen and couldn't find them.”

“I wonder what could have happened to them,” Abuela mused.

Oscar, who had been quietly savoring the last bit of milk-caramel cookie started to cough. He coughed until Abuela excused him and led him to his room. It looked fake to me. I figured he wanted to get away for some reason. But why? Abuela came in through the hallway and instantly disappeared into the kitchen.

My aunts kept talking with my father, as though nothing had happened. But I knew something interesting was going on behind the closed kitchen door. I had to find out what it was, so I excused myself and followed Abuela.

Abuela Elena was in front of the pantry sifting through bottles, cans, and boxes. As she was about to remove a pile of table linen, a small paper package from the bakery appeared in the corner of the shelf. It had a tear in it, and

alfajor

crumbs lay all around it.

“¡Qué mala pata!”

exclaimed Elvira with a clap of her hands. “What bad luck!” She proceeded to pick up the torn package.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Your brother secretly ate two

alfajores

and hid the third one for later,” said Abuela Elena, motioning to Elvira to throw away the package and its contents.

“And a mouse got to it before he did!” Elvira sighed as she wiped the shelf with a soapy rag. “It's too late to buy any more this evening.”

I stood there frozen as I watched Elvira clear away all the crumbs from the precious

alfajor

and throw them into the garbage. The rage bubbling inside me soon gave way to numb disbelief. Abuela Elena tenderly took my hand and led me back into the dining room. With my well-learned good manners, I forced a smile and sat down to tea again.

Â

The next morning at breakfast, I found Oscar's seat empty. Abuela told me had had been up all night with indigestion. In the early hours of the day he was quite weak. But as time went by he became hungry once again, and that meant he felt much better. That is, until Mamá told him that for the next eighty-nine days, whenever we had guests for tea, I was to have

his

share of

alfajores

â as well as mine.