Salt (58 page)

S

ICHUAN PROVINCE IS

the size of France with twice the population. In the mid–twentieth century, when the Chinese population expanded at an unprecedented rate, the number of inhabitants in Sichuan grew to its current 100 million people, most of them crowded into the eastern half of the province. The west is a desert leading to Tibet. Sichuan also has a bamboo mountain forest that is home to the earth’s only remaining wild panda population. But most of the province is subtropical, like the American South.

The Sichuan landscape is a tribute to the water management skills of the heirs of Li Bing, the third century

B.C.

governor, with dikes and sluices breaking up waterways into a lush green quilt of flooded rice paddies, dark-soiled vegetable patches, cypress groves, and bamboo stands. Soil erosion is rare and wasted space even rarer. But despite this rich agriculture, the farmers seem poor. They produce an enormous quantity of food, but in their villages built along the dirt trails that connect paddies and fields, there are too many people. They live in patched and crumbling mud-and-straw houses, a few still decorated with huge posters of Mao.

Children hike miles to school along the dikes between rice paddies and up into the green mountains. Women with brightly colored parasols carry children on their backs in wicker strap-on seats that are made only in Sichuan. A frequent sight in the Sichuan countryside, one seen in Marco Polo’s China, is noodles more than seven feet long, hung out to dry like laundry on a line.

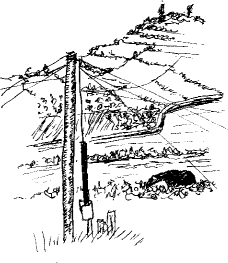

Although most of the big derricks have been torn down, a few small brine wells remain. One in Dayin, west of the Sichuan capital, Chengdu, had a single post the height of a telephone pole. The well was only 1,000 feet deep, a considerable depth by any but Chinese standards, but at that relatively shallow depth the brine was weak, only 10 percent salt. That was why the Chinese learned deep drilling.

A farmer in a worn blue Mao jacket who grew grains, vegetables, and sweet potatoes on the land said that in the 1960s salt had been his most profitable crop. Asked who built the well, he shrugged and said, “Oh, that well has been there forever.”

The blue jackets, which during the 1950s and 1960s were the only clothes available in China, along with matching pants and caps, are still commonly seen in the countryside. It is not a political statement, just people too poor for new clothes. The matching pants are seldom seen anymore. Pants wear out, but a good jacket lasts forever.

The Dayin well.

Next to the pole at the Dayin well, there was a stone stool. A lone farmer would sit on the stone with his feet peddling a bamboo wheel, which would raise and lower a bamboo tube into the 1,000-foot hole. The brine was piped into a tank, over which stood a much larger bamboo wheel about ten feet tall, with bamboo cups lashed to its rim. This larger wheel was turned by a man walking carefully inside the wheel, a simpler version of the medieval wheel in Salsomaggiore. The wheel would scoop up the brine and drop it on top of a wall of dried branches. As the brine dribbled down the branches, with the help of wind and sun, it would become more concentrated. After it dripped into the tank below, it was ready to be boiled for evaporation. Since this well had no natural gas, coal, which is abundant in the area, was used for fuel.

In 1998, the government salt corporation sealed the well, capped the small hole in the ground with concrete, along with many other wells in the area, and ruled that such salt was substandard and illegal to sell.

“But there’s still brine there,” the farmer insisted.

By the standards of Chinese history, salt producers are no longer tightly controlled. The tax is on selling, not producing, and it is no longer a major source of revenue. But the iodine requirement, the reason the little well in Dayin was capped, is often seen as a new form of government control of salt.

The World Health Organization and UNICEF urge salt producers to include iodine in their salt to prevent goiter, an enlargement of the thyroid gland. Since everyone uses salt, it is an ideal distribution vehicle. They claim that 1 billion people worldwide are at risk of iodine deficiency. In addition to thyroid enlargement, symptoms of iodine deficiency can include nervousness, increased and irregular heart rate, and muscle weakness. Iodine deficiency can also lead to mental disability in children.

Iodine was used to cure goiter even before it was known to be iodine. Humphry Davy, among others, had suspected that iodine was an element, but it was Jean-Baptiste Dumas, the French chemist and founder of one of the first schools of industry in France, who, in 1819, proved that iodine was present in natural sponge, which had been a standard treatment for goiter.

In treating goiter, once again, China was centuries ahead of the West. A fourth-century-

A.D.

Chinese physician, Ko Hung, prescribed an alcoholic extract from seaweed for goiter. Many seaweeds are rich in iodine, which is why the Japanese, who not only eat a great deal of seaweed but fertilize crops with it, have had relatively little experience with the disease. In China, as in most of Asia, goiter has little history in coastal regions but has often been problematic in mountainous interior provinces, including Sichuan.

American salt is usually iodized. The British, having few cases of goiter, do not iodize, and the French sometimes, but not always, iodize their salt. Among afflicted populations, iodized salt is well appreciated. Myanmar, formerly Burma, has an iodized salt policy, but the tribesmen in the remote highlands cannot get the treated salt and instead trade illegally across the Chinese border for it. In exchange for Chinese salt, which they believe will help with their goiter problem, they offer rare, endangered wildlife species. The Chinese value these animals for folk medicine. The tongues of the antelopelike serow are thought to cure headaches, and the nimble legs of goatlike gorals are ground into a powder used on aching joints. Rare Himalayan black bears are killed for their gall bladders, which are used to treat liver and stomach ailments. The commerce across the Myanmar border is especially tragic because much of this black-market Chinese salt is in fact not iodized and so will not help them with their goiter problem.

Iodized salt has become controversial in developing countries where government control of salt is a historic issue. In 1998, India followed China’s 1995 decision and, under pressure from the world health community, banned the sale of noniodized salt. In both countries, the move was popular with health authorities, doctors, and scientists, but very unpopular with small independent salt producers.

As China became a modern state, its salt became modern salt—small uniform grains with iodine added. And like other modern people, the Chinese have started longing for salt that is a bit more irregular, perhaps less pure. Impurities are things that were left in, and many prefer this to chemicals that are added. The controversy over iodized salt is in part the distrust of chemical additives that have become part of life in virtually all cultures. In the Jewish religion, most rabbis state that salt must be non-iodized to be considered kosher for Passover.

In Sichuan, wary consumers insist that iodine gives salt a peculiar taste. But small producers also suspect that the ban is a government conspiracy to put them out of business and once again give state salt companies a monopoly. Peasants, such as the family at the little foot-operated well that was capped in rural Dayin, do not have the knowledge or money to meet government standards for iodized salt.

In September 2000, the Indian government repealed its ban on noniodized salt under pressure from Hindu nationalists and Gandhians who recalled Gandhi’s assertion that every Indian had a right to make salt. But the Chinese authority did not seem inclined to go back on its decision to ban noniodized salt. Li Fude of the government salt agency for Sichuan Province, the General Sichuan Salt Company, said, “It was decreed by the prime minister himself.” He said it like an ancient bureaucrat speaking of the emperor.

T

HE CHINESE HAVE

been slow to part not only with their emperors but with many ancient ideas. Among the lingering old ways in modern China are attitudes about food—about salt and seasoning and how to construct a meal. Many of these ideas, though notably different from current Western thought, did exist in the pre-Rennaissance West. The differences between China and the West on food are far greater today than 1,000 years ago.

The Chinese seem ready to eat anywhere and anytime. City streets and rural roads are lined with food stalls. On the trans-Siberian railroad that runs from Moscow to Beijing, the heater at the end of cars that the Russians use to make tea is used by the Chinese to prepare whole meals. They crowd into the dark, closetlike space and chop vegetables and spread out seasonings. Not only do they cook and eat constantly, but they talk a great deal about the meaning of their foods. Food sometimes seems a Chinese obsession, and the culture at times seems almost afflicted with epicurism.

The contemporary Chinese novelist Lu Wenfu wrote:

The word gourmet is pleasing to the ear, perhaps also to the eye. If you explain it in simple everyday language, however, it’s not so appealing: A gourmet is a person who is totally devoted to eating.—Lu Wenfu,

The Gourmet

, 1979

In China, southern food, especially Cantonese, is usually said to be the best. But after 1949, when Mao Zedong from Hunan and Deng Xiaoping from Sichuan came to power, the hot spicy food, la, from southwestern China, came into official fashion. “If you don’t eat la, you are not a revolutionary” became a popular saying.

In 1959, a restaurant for the political elite was established in a Beijing house of gardened courtyards built for the son of a seventeenth-century emperor. Predictably, it was a Sichuan restaurant, and was simply named the Sichuan Restaurant. Zhou Enlai, the long-time premier, and Deng Xiaoping were regulars. For years it was considered one of the few good restaurants in Communist Beijing.

The restaurant remained a symbol of the times when, in 1996, its antique setting was bought by a Hong Kong entrepreneur, who turned the house into a private members-only club with the obsequious gentlemanly service reminiscent of British colonialism. The so-called Chinese takeover of Hong Kong has in fact meant that many Communist Party relics have been bought up by Hong Kong entrepreneurs. The Sichuan Restaurant has survived in three less sumptuous Beijing locations. Its head chef, Yu Jiamin, is a native of Beijing who, in 1970, at age nineteen, began apprenticing in Sichuan cuisine. “For me, it is the most complete cuisine, the only one that completely uses six flavors,” he said.

The notion of balancing principal flavors is central to Chinese cooking. The six of Sichuan food are expressed as a musical jingle: “ma, la, tian, suan, xian, ku.” Ma, the spicy huajiao, is the sixth flavor unique to Sichuan, though la, hot peppers, is also typical of the area.

Tian,

meaning “sweet,”

suan,

meaning “sour,”

xian,

meaning “salty,” and

ku,

meaning “bitter,” are universal.

Each dish will have a flavor, or ideally a combination of flavors, ma-la being the most famous Sichuan combination. Xian, salty, is the most used flavor, a central motif. It is considered a balance to all the others. Salt is believed to bring out sweetness and moderate sourness. In ancient times, tea was prepared in Sichuan with salt and ginger added. Salty and spicy, xian-la, is such a popular Sichuan combination that it has been bottled in the form of soy sauce and hot peppers. Xian-la is also a recurrent theme in other warm climates from Cajun Louisiana to Vietnam, where ground hot pepper and salt are served on limes, grapefruit, or pineapple to moderate the acid taste.

Other books

Rugged and Relentless by Kelly Hake

Her Demon Lover Trilogy (Erotic Romance Series) by Clark, C.S.

The Water Rat of Wanchai by Ian Hamilton

Possessing the Secret of Joy by Alice Walker

Demon Possession by Kiersten Fay

The Gentle Seduction by Marc Stiegler

Ms Virtue Super Heroine Girls' Night by Cat Wilder

Bane: Trillionaire Shifter Club Book One by Rosette Bolter

I'm All Yours by Vanessa Devereaux

Gemini Rain by Lj McEvoy