Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 (48 page)

Read Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 Online

Authors: Total Recall

“And Michael’s on his way into town. Agnes called him

after this latest incident; he wants to stay close until Agnes and Calia fly

home on Saturday. He’s already in the air, landing at O’Hare in an hour or so.”

“Even so, I think you should hang on, although there

probably isn’t any other risk to Calia,” I said. “Just in case that prize

fanatic Posner decides to carry on for his fallen disciple.”

He agreed, but added that baby-sitting was harder work

than moving furniture. “I’d rather carry a grand piano up three flights of stairs.

At least when you got there you’d know where the piano was, and you’d be done

for the day.”

I switched my house phone over to the answering

service while I soaked, obsessively sponging my breasts as if blood had seeped

through the pores of my skin. I shampooed my hair several times as well before

I finally felt clean enough to leave the tub.

Wrapped in a terry cloth robe, I returned to the

living room: I’d dropped the accordion file on the piano bench when I’d run

into the apartment. For a long moment I stared down at Ulrich’s disfigured

face, which looked even worse for the blood that had seeped onto it.

I’d been wanting to see these papers since Paul showed

up at Max’s last Sunday. Now that they were within my reach I almost couldn’t

bear to read them. They were like the special present of my childhood

birthdays—sometimes wonderful, like the year I got roller skates, sometimes a

disappointment, like the year I longed for a bicycle and got a concert dress. I

didn’t think I could bear to open the file and find, well, another concert

dress.

I finally undid the black ribbon. Two leather-bound

books fell out. On the front of each was stamped in peeling gold letters

Ulrich

Hoffman

. So that was why Rhea Wiell had smirked at me: Ulrich was his first

name. I could have called every Ulrich who’d ever lived in Chicago and never

found Paul’s father.

A black ribbon hung from the middle of one of the

books. I set the other down and opened this one to its marker. The paper, and

the ornate script on it, looked much the same as the fragment I’d found in

Howard Fepple’s office. A person who was fond of himself, that was what the

woman at Cheviot Labs had said, using expensive paper for keeping accounting

notes. A domestic bully, king only of the tiny empire of his son? Or an SS man

in hiding?

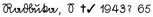

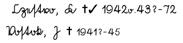

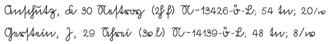

The page I was looking at held a list of names, at

least twenty, maybe thirty. Even in the difficult script, one name in

particular halfway down the page caught my eye:

Next to it, in a hand so heavy it cut through the

paper, Paul had written in red,

Sofie Radbuka. My mother, weeping for me,

dying for me, in heaven all these years praying for me.

My skin crawled. I could hardly bear to look at the

page. I had to treat it as a problem, a conundrum, like the time in the PD when

I’d represented a man who had skinned his own daughter. His day in court where

I did my best, my God, because I’d managed to dissociate myself and treat it as

a problem.

All the entries followed the same format: a year with

a question mark, and then a number. The only variation I saw was that some had

a cross followed by a check mark, others just a cross.

Did this mean they had died in 1943, or ’41? With 72

or 45 something.

I opened the second book. This one held similar

information to the scrap I’d found in Fepple’s office, columns of dates, all

written European style, most filled in with check marks, while some were blank.

What had Howard Fepple been doing with a piece of Ulrich Hoffman’s old Swiss

paper?

I sat down hard on the piano bench. Ulrich Hoffman.

Rick Hoffman. Was that Paul Radbuka’s father? The old agent from Midway with

his Mercedes, and the books he carried around with him to check off who paid

him? Whose son had an expensive education, but never amounted to anything?

But—had he sold insurance in Germany as well? The man who’d owned these books

was an immigrant.

I dug Rhonda Fepple’s number out of my briefcase. Her

phone rang six times before the answering machine picked up, with Howard

Fepple’s voice eerily asking for me to leave a message. I reminded Rhonda that

I was the detective who had been to her house on Monday. I asked her to call me

as soon as possible, giving her my cell-phone number, then went back to stare

at the books again. If Rick Hoffman and Ulrich were the same man, what did these

books have to do with insurance? I tried to match the entries with what I knew

of insurance policies, but couldn’t make sense of them. The front of the first

book was filled with a long list of names, with a lot of other data that I

couldn’t decipher.

The list went on for pages. I shook my head over it. I

squinted at the difficult ornate writing, trying to interpret it. What about it

had made Paul decide Ulrich was with the

Einsatzgruppen

? What was it

about the name Radbuka that had persuaded him it was his? The papers were in

code, he’d screamed at me outside the hospital yesterday—if I believed in Rhea

I’d understand it. What had she seen when he’d shown these pages to her?

And finally, who was the Ilse Bullfin who had shot

him? Was she a figment of his imagination? Had it been a garden-variety

housebreaker whom he thought was the SS? Or was it someone who wanted these

journals? Or was there something else in the house that the person had taken as

she—he—whoever—tossed all those papers around.

Even laying out these questions on a legal pad at my

dining room table didn’t help, although it did make me able to look at the

material more calmly. I finally put the journals to one side to see if there

was anything else in the file. An envelope held Ulrich’s INS documents,

starting with his landing permit on June 17, 1947, in Baltimore, with son Paul

Hoffman, born March 29, 1941, Vienna. Paul had X’d this out, saying, Paul

Radbuka, whom he stole from England. The documents included the name of the

Dutch ship they had arrived on, a certification that Ulrich was not a Nazi,

Ulrich’s resident-alien permits, renewed at regular intervals, his citizenship

papers, granted in 1971. On these, Paul had smeared, Nazi War Criminal: revoke

and deport for crimes against humanity. Paul had said on television that Ulrich

wanted a Jewish child to help him get into the States, but there wasn’t any

reference to Paul’s religion, or to Ulrich’s, in the landing documents.

My brain would work better if I got some rest. It had

been a long day, what with finding Paul’s body and his unnerving refuge. I

thought of him again as a small child, locked in the closet, terrified, his

revenge now as puny as when he’d been a child.

Confession

I

slept

heavily, but unpleasantly, tormented by dreams of being locked in that little

closet with swastikaed faces leering down at me, with Paul dancing dementedly

outside the door like Rumpelstiltskin, crying, “You’ll never know my name.” It

was a relief when my answering service brought me back to life at five: a woman

named Amy Blount had called. She said she had offered to look at a document for

me and could stop by my office in half an hour or so if that was convenient.

I really wanted to get up to Max’s. On the other hand,

Mary Louise would have left a report on her day’s interviews with Isaiah

Sommers’s friends and neighbors. Come to think of it, Ulrich Hoffman’s books

might mean something to Amy Blount: after all, she was a historian. She

understood odd documents.

I put Ninshubur in the dryer and called Ms. Blount to

say I was on my way to my office. When I got there, I made copies of some of

the pages in Ulrich’s books, including the one with Paul’s heavy marginalia.

While I waited for Ms. Blount, I looked over Mary

Louise’s neatly typed report. She had drawn a succession of blanks on the South

Side. None of Isaiah Sommers’s friends or coworkers could think of anyone with

a big enough grudge against him to finger him to the cops.

His wife is an angry woman, but at the bottom I

believe she is on his side—I don’t think she set him up. Terry Finchley tells

me the police right now have two competing theories:

1. Connie Ingram did it because Fepple tried to

assault her. They don’t like this because they believe what she says about not

going to his office. They do like it because her only alibi is her mother, who

sits in front of the tube most nights. They also can’t get around the forensic

evidence showing that Fepple (or someone) entered his “hot” date in his

computer on Thursday, when everyone agrees Fepple was still alive.

2. Isaiah Sommers did it because he thought Fepple was

robbing his family of ten thousand dollars they all could use. They like this

better, because they can actually put Sommers at the scene. They can’t prove he

ever owned a 22-caliber SIG, but they can’t trace the gun anyway. Terry says

they’d risk going to court if they could completely discount Connie as a

suspect; he also says they know that with Freeman Carter and you acting for

Sommers, they need to have cast-iron evidence. They know Mr. Carter would

demolish them in court since they can’t put the SIG in Sommers’s hands any more

than anyone else’s.

The only odd thing here is Sommers’s cousin Colby—this

is his other uncle’s son, the one he told you might have stolen the policy to

begin with; he hangs on the fringe of Durham’s Empower Youth Energy. He’s been

flashing cash lately, and everyone is surprised, because he never has any.

This can’t be the original life-insurance money,

I scribbled on the page,

because that was cashed

in almost a decade ago. I don’t know if it’s significant or not, but poke at it

tomorrow morning, see if you can find anyone who knows where he got it.

As I dropped the report back on Mary Louise’s desk,

Amy Blount came to the door. She had on her professional wardrobe, the prim

tweed suit with a severe blue shirt. Her dreadlocks were once again tied back

from her face. With the formal attire her manner had become more guarded again,

but she took Ulrich’s two journals and looked at them carefully, comparing them

with the photocopy of the fragment I’d found in Fepple’s office.

She looked up with a rueful smile that made her seem

more approachable. “I hoped I was going to perform some kind of hocus-pocus on

this, impress you beyond expression—but I can’t. If you hadn’t told me you’d

found it in a German man’s home, I’d have guessed some Jewish organization—the

names all look Jewish to me, at least the ones on the document you found in the

Midway Insurance office. Someone was keeping track of these people, marking off

when they died; only Th. Sommers is still alive.”