Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 (54 page)

Read Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 Online

Authors: Total Recall

“Does someone in the building have keys? Could I get

in to see if she’s all right?”

He consulted a list. Lotty had left Max and my names

as people to call in any emergency; he guessed the super could let me in if I

didn’t have keys. When was I coming? In twenty minutes? He’d get Gerry up from

the basement, where he was supervising a boiler-repair crew.

Mary Louise called as I was leaving. She was on the

South Side with Gertrude Sommers—yes, the client’s aunt—who wanted to tell me

something in person. I’d forgotten about sending Mary Louise down to check on

the client’s dubious cousin—I’d left the note for her yesterday afternoon, but

so much was going on it seemed like a month ago.

I tried not to sigh audibly. I was tired, and tired of

running from one end of Chicago to the other. I told Mary Louise that unless

some crisis developed at Lotty’s place, I’d be at Gertrude Sommers’s apartment

in about ninety minutes.

Heard on the Street

T

he doorman

at Lotty’s building had seen me a number of times, but he and Gerry, the

building super, still insisted on proof of my identity before Gerry took me up

to the eighteenth floor. The precaution, which would normally have made me

impatient, gave me some reassurance about Lotty’s safety.

When we got to her apartment, Gerry rang the bell

several times before undoing her locks. He went with me through the rooms, but

there was no sign of Lotty, and no sign that any violent struggle had taken

place.

While Gerry watched in mounting disapproval, I looked

through the drawers in the side room that Lotty uses as a home office, and then

in Lotty’s bedroom, for Ulrich’s journals. Gerry followed me from room to room

while I imagined the places that people conceal things—behind clothes, under

rugs and mattresses, inside kitchen cabinets, behind pictures on the wall,

slipped in among the books on her own shelves.

“You don’t have a right to be doing that, miss,” he

said when I was poking through Lotty’s underwear drawer.

“You married, Gerry? Kids? You know if your wife or

one of your daughters was having a dangerous pregnancy who everyone would tell

you she should see? Dr. Herschel. Who takes her duties so seriously she never

even calls in sick unless she’s running a fever that she thinks would affect

her judgment. Now she’s suddenly vanished. I’m hoping for any sign that would

tell me whether she left voluntarily or not, whether she packed a bag,

anything.”

He wasn’t sure he believed me, but he didn’t make

further efforts to stop me. Of Ulrich’s journals there wasn’t a sign, so she

must have taken them with her. She had left under her own steam. She must have.

“Is her car in the garage?” I asked.

He called down to the doorman on his walkie-talkie;

Jason said he’d go out to look. That’s how an intruder could infiltrate: wait

until the doorman goes to the garage, then follow another tenant inside.

When we got downstairs, Jason was back at his station.

Dr. Herschel’s car was here—he once again abandoned his station to take me out

to look. It was locked, and I didn’t want to show off my parlor tricks by

opening it in front of him, so I peered through the tinted windshield. Unlike

me, Lotty doesn’t leave her car strewn with papers, old towels, and stinking

T-shirts. There wasn’t anything on the seats.

I gave each of them my card and asked Jason to

question people as they came home about whether anyone had seen her leave.

“That way we can keep it casual,” I said when he started to object. “Otherwise

I’ll have to bring the police in, which I’m very reluctant to do.”

The two men exchanged glances: the building management

would be annoyed if the cops came around to question the tenants. They pocketed

their tens with suitable dignity and agreed not to let anyone up to Dr.

Herschel’s apartment unless Max or I was here.

“And you do keep an eye on the lobby, even when you’re

running another errand?” I persisted.

“We don’t leave the lobby unattended, ma’am.” Jason

was annoyed. “I can always see it on the TV monitor in the garage. And when I

go on break, Gerry stays here to cover for me.”

I knew it wasn’t a foolproof system, but I’d lose

their cooperation if I criticized it any further. I sat in the Mustang for a

bit, massaging the back of my neck. What had happened to her? That Lotty had a

life of which I knew nothing had become abundantly clear in the last ten days.

Just because she’d hugged her secrets to herself, did that mean I had to

respect this secrecy? But conversely, did my friendship, my love, my concern,

any of those give me the right to invade a privacy she’d gone to such lengths to

protect? I thought it over. Probably not. As long as those damned books of

Ulrich’s weren’t going to put her at risk. But they might. If only I could find

someone who could interpret them for me. Maybe they would mean something to

Bertrand Rossy.

I slowly put the car into gear and made the difficult

drive to the South Side. Every week it gets harder to cross the heart of

Chicago. Too many people like me, sitting one to a car. At the entrance to the

expressway at North Avenue, I stopped for gas. Price was still going up. I know

we pay less than half what they do in Europe, but when you’re used to cheap

fuel a thirty-dollar fill-up is a jolt. I crawled down the Ryan to

Eighty-seventh, the exit nearest Gertrude Sommers’s.

At her building, nothing seemed to have changed from

two weeks ago, from the derelict Chevy out front to the despairing wail of the

baby within. Mrs. Sommers herself was still rigidly erect in a dark, heavily

ironed dress, her expression as forbidding as before.

“I told that other girl she might as well go,” she

said when I asked if Mary Louise was still there. “I don’t like to talk to the

police about my family. Even though she says she’s private, not with the police

anymore, she looks and talks like police.”

She gave the word a heavy first-syllable stress. I

made an effort to put Lotty out of my mind, to concentrate on what Gertrude

Sommers had decided to tell me.

She waved me to a chair at the pressed-wood table

along the far wall, then seated herself, with the sighing sound of stiff fabric

against stocking. Her back was rigidly upright, her hands folded in her lap,

her expression so forbidding that it was hard for me to meet her gaze.

“At Bible study on Wednesday night the reverend spoke

to me. About my nephew. Not my nephew Isaiah, the other one. Colby. Do you

think if his father had named him for a prophet, like Mr. Sommers’s other

brother named Isaiah, Colby would be an upright man, as well? Or would other

temptations have always proved too strong for him?”

Whether this was a rhetorical question or not, I knew

better than to try to answer. She was going to need time to come to the point.

I would have to let her get there on her own. I slipped a hand into my pocket

to turn off my cell phone: I didn’t want its ringing to interrupt her.

“I’ve been worried about Isaiah since Mr. Sommers

passed. He found money for the funeral out of his own pocket. He took it on

himself to hire you, with money out of his own pocket, to find out what

happened to Mr. Sommers’s life-insurance money. Now, for acting like that good

Samaritan, the police are hounding him, with that wife of his gnawing on him

from behind. That’s a good job he has at the engineering works, a fine job.

She’s lucky to have a man who’s a hardworking churchgoer, like Mr. Sommers was

before him. But she’s like a baby, wanting what she can’t have.”

She looked at me sternly. “In my heart I’ve been

blaming you for Isaiah’s troubles. Even though Isaiah kept saying you were

trying to end them, not foment them. So when the reverend spoke to me about my

nephew Colby, I didn’t want to hear, but the reverend reminded me, ‘Ears they

have and hear not, eyes they have and see not.’ So I knew the time had come for

me to listen. Um-hmm.”

She nodded, as if she were lecturing herself in that

little grunt. “So I listened to the reverend telling me that Colby was flashing

money around the neighborhood, and I thought, What are you trying to tell

me—that Colby has my husband’s insurance money? But the reverend said, nothing

like that. Colby got paid for helping do a job.

“‘A job,’ I said. ‘If my nephew Colby is getting money

for working, then I’m on my knees to praise Jesus.’ But the reverend told me,

not that kind of job. The reverend said, ‘He’s been hanging out with some of

those Empower Youth men.’ And I said, ‘The alderman does a lot of good in this

neighborhood, I won’t believe any ill of him.’ And the reverend said, ‘I hear

you, Sister Sommers, and I don’t believe ill of him, either. I know what he did

for your son when he was a boy, what he did for you and Mr. Sommers when your

boy was afflicted with the scourge of muscular dystrophy. But a man doesn’t

always know what the left hand of his left hand is doing. And some of the

alderman’s left hands are finding their way into people’s pocketbooks and cash

registers.’”

She gave another little grunt, “un-hnnh,” her lips

folded over in bitterness at having to repeat ill of her family to me, a

stranger, a white woman. “So the reverend says, ‘I’ve been hearing that your

nephew Colby got paid good money to make a telephone call to the police. To

tell them his cousin Isaiah had been in the office of that insurance agent who

defrauded you of your husband’s money and then got murdered. And if ever Cain

hated Abel for being righteous in the eyes of the Lord, your nephew Colby has

always hated his cousin Isaiah with that same hatred. I hear,’ the reverend

said, ‘I hear he gladly made that phone call. And I hear that when these same

left hands of the alderman’s left hand wanted a gun, that Colby knew where to

find it. And when they went breaking into an apartment in Hyde Park with a

blowtorch, Colby was glad to stand lookout for them.’

“‘I won’t go to the police against my own family,’ I

told the reverend. ‘But it’s not right for Isaiah to lie in jail, as he will if

the worst comes about from these police questions, because of the hatred of his

cousin.’ So when the other girl came around this morning, wanting to ask me

about Colby—because someone had been telling her stories about him as well—I

remembered you. And I saw the time had come to talk to you.”

The news was so startling that I hardly knew what to

say. Alderman Durham’s EYE team deployed to kill Howard Fepple? That hardly

seemed possible. In fact, I didn’t think it could be possible, because the

guard at the Hyde Park Bank would have noticed them—you wouldn’t mistake

Durham’s EYE troops for expectant parents going up to a Lamaze class. But it

must have been some EYE hangers-on who broke into Amy Blount’s apartment.

I pressed my palms against my eyes, as if that would

bring any clarity to my vision. Finally I decided to tell Gertrude Sommers a

good deal of the events of the last week and a half, including the old journals

that Ulrich Hoffman entered his payments in.

“I don’t understand any of this,” I finished. “But I

will have to talk to Alderman Durham. And then—I may have to talk to the

police, as well. One man is dead, another critically wounded. I don’t

understand what possible connection there is here between these old books of

Hoffman’s and the alderman—”

I halted. Except that Rossy had singled out Durham on

the street on Tuesday. He was just back from Springfield, where they’d killed

the Holocaust Asset Recovery Act, where Ajax had thrown its weight behind

Durham’s slave-reparations rider. And the demonstrations had stopped.

Rossy was from a European insurance company. Carl had

thought Ulrich’s records looked similar to the ones a European insurance agent

had kept on his father many years ago. Was that what connected Rossy to the

Midway Insurance Agency?

I picked up my briefcase and pulled out the

photocopies of Ulrich’s journal. Mrs. Sommers watched me, affronted at first by

my inattention, then interested in the papers.

“What is that? It looks like Mr. Hoffman’s

handwriting. Is this his record of Mr. Sommers’s insurance?”

“No. But I’m wondering if it’s a record of someone

else’s insurance that he sold in Europe sixty-five years ago. Look at this.”

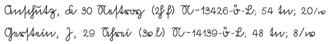

“But it isn’t an

E,

it’s an

N

. So it

can’t be an Edelweiss policy number. Or it is, but they have their own company

code.”

“I suppose you know what you’re talking about, young

lady. But it doesn’t mean a thing to me. Not one thing.”