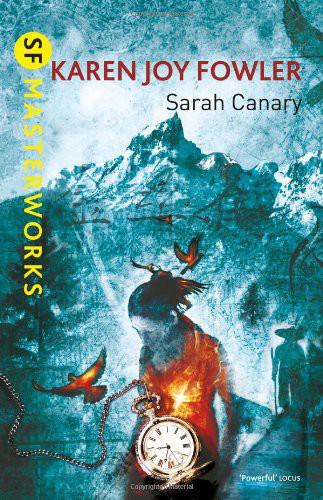

Sarah Canary

| Sarah Canary | |

| Karen Joy Fowler | |

| Plume (1990) | |

| Rating: | *** |

| Tags: | Science Fiction, Fiction, General |

When black cloaked Sarah Canary wanders into a railway camp in the Washington territories in 1873, Chin Ah Kin is ordered by his uncle to escort "the ugliest woman he could imagine" away. Far away. But Chin soon becomes the follower. In the first of many such instances, they are separated, both resurfacing some days later at an insane asylum. Chin has run afoul of the law and Sarah has been committed for observation. Their escape from the asylum in the company of another inmate sets into motion a series of adventures and misadventures that are at once hilarious, deeply moving, and downright terrifying.

~ * ~

Sarah Canary

Karen Joy Fowler

No copyright  2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

~ * ~

You only comprehend things which you perceive. And as you persist in regarding your ideas of time and space as

absolute

, although they are only

relative,

and thence form a judgment on truths which are quite beyond your sphere, and which are imperceptible to your terrestrial organism and faculties, I should not do a true service, my friend, in giving you fuller details of my ultra-terrestrial observations. . .

CAMILLE FLAM MARION

LUMEN,

1873

~ * ~

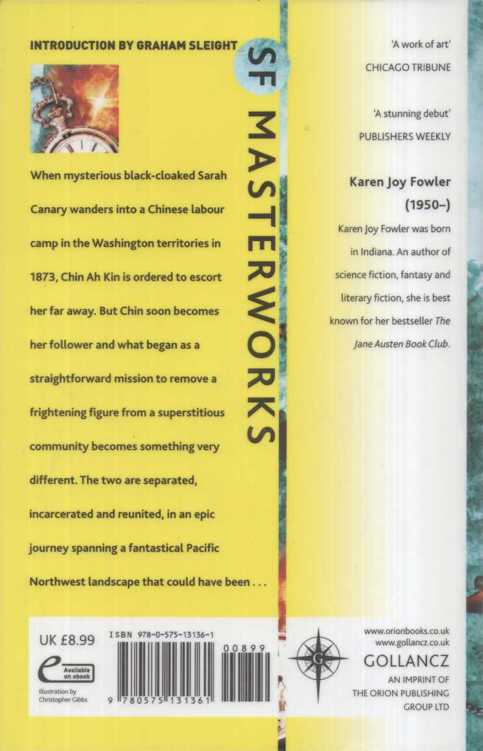

INTRODUCTION

What do you do when you encounter something incomprehensible, something entirely beyond your experience? Do you try to learn how it works? Do you dismiss or ignore it? Do you work out how it might be used or exploited? Do you fear it or love it? Those are the kinds of questions posed by the subgenre of SF called the First Contact story, and by

Sarah Canary.

The classic version of the First Contact story depicts an encounter between humanity and aliens. Very often, the body of the story is a process of working-out, of two different viewpoints or conceptual worlds coming to understand each other.

Sarah Canary

is not like that.

Before she published this, her first novel, in 1991, Fowler had written a clutch of superb short stories that had been collected as

Artificial Things

(1986). On the strength of this, she won the John W Campbell Award for best new writer. She’s since gone on to write stories both within and outside the fantastic. Probably her most famous work to date is the mainstream

The Jane Austen Book Club

(2004), which was subsequently filmed. Feminist concerns have been particularly prominent in her career, and she was one of the founders of the Tiptree Award, presented annually to works of SF that expand or explore our understanding of gender.

The premise of

Sarah Canary

is spelt out within a few pages. A strange woman wanders into a railroad workers’ camp on the west coast of the US in 1873. She speaks no known human language, and seems- oblivious to much of what’s going on around her. Chin, the worker who first encounters her, has his own theories about who she might be. The body of the book follows the travels of Sarah Canary, Chin, and a growing band of other followers through this milieu (the name ‘Sarah Canary’ is derived by one of these followers from her strange, fluting way of ‘speech’). By the end of the book, she has become a

cause celebre,

an object of fascination for many. But the book offers no certainty as to what she really is.

That brings up the question of whether, or in what sense, this is an SF novel at all. It’s true that it can be read as entirely mimetic, as a pure historical novel. Sarah Canary’s behaviour could be explained as some combination of disability or strange upbringing. As I’ve said, each of the major characters who encounters Sarah Canary brings their own interpretation of what she might be. Those theories are inevitably rooted in those characters’ outlooks and backgrounds. Among the other issues the book raises, not least is the question of how observation affects the thing being observed. My contention is that it’s much realer to create a reading of the novel as science-fictional. If Sarah is truly an extra-terrestrial of some kind, it makes much more sense of her eventual fate. It also gives much more sense to some emphases in the text that otherwise seem arbitrary, weirdly underlined for no particular reason. One of these are a series of references to butterflies, to creatures changing their form. A second strand is a set of mentions of ghosts and dream-creatures, especially in Chin’s thinking about Sarah Canary. Finally, the ‘Canary’ in her name echoes back and forth with images of wings and imprisonment that permeate the book. It is, I’d suggest, very much easier to see these threads of imagery as deliberate pointers to some kind of fantastic reading - though, of course, there’s no certainty about what kind. To be clear, I’m not suggesting that Sarah Canary is (say) a ghost. I am suggesting that some of her characteristics might be describable in the same ways that we describe ghosts - or aliens, or butterflies, or . . .

The epigraphs from Emily Dickinson are also a pointer here, I think. Dickinson’s poetry always hovers on the edge of revelation, on the edge of something that

cannot be said.

Its compacted syntax and sudden leaps of imagination hedge around things that are beyond words. So, for instance, the epigraph to Chapter Ten is clearly about the aftermath of something terrible, but something not sayable. It’s a difficult lesson for a book to convey: that the mystery at the heart of the book cannot be set out in the book. Moreover, the best efforts of some well-intentioned people (and some poorly-intentioned people) will necessarily fail at that task, and may even do damage.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. The reader now may look back on the world of the 1870s and raise an amused eyebrow at the weird conceptual schemas into which this novel’s characters try to cram Sarah Canary. Some of these ideas are set out in the brief historical notes set into the book. Other fads and strangenesses are embodied in the main narrative. But are we any better now? Would our science, or our other tools for knowing, be any better at comprehending a Sarah Canary? The very last paragraphs of the book carry some strong hints that they wouldn’t. 1990 was just as strange a time as the 1870s — and no doubt 2012 is as well (imagine what the internet would say about Sarah Canary). For some questions, we’re stuck irretrievably with our own ways of seeing. SF is usually about solving problems in some way, about finding a definitive reading for them. Sarah Canary is about accepting that, sometimes, there’s no definitive reading. Fowler’s immense skill in this book is directed at a kind of reticence, at not giving us answers while still making us ask questions.

Graham Sleight

~ * ~

i

The years after the American Civil War were characterized by excess, ornamented by cults and corruptions. Calamity Jane rode her horse through Indian country, standing on her head, her tangled hair loose along the horse’s sides. Chang and Eng, P. T. Barnum’s Siamese twins, hunted boar, fathered children, and drank like the gentlemen they were. The Fox sisters held seances and secretly cracked their toe knuckles to dissemble communication from the beyond. T. P. James, a psychic/ mechanic in Vermont, channeled Charles Dickens, allowing him to complete his final book,

The Mystery of Edwin Drood,

posthumously. Big Jim Kinelly plotted the kidnap of Abraham Lincoln’s body. Brigham Young married and Victoria Woodhull told everyone who was sleeping with whom. Football and lawn tennis had their first incarnations.

In 1871, strange events took place in the skies over the central and northern United States. Eyewitness accounts allude to spectacular meteor showers, ghostly lights, and, on the ground, a number of fires whose origins were unknown and whose behavior was, in some ways, disquietingly unfirelike.

In 1872, the residents of the asylum for the insane in Steilacoom, Washington, were thrown out of their beds by earthquakes resulting from volcanic activity in the Cascade Mountains. The event was so profound it cured three of the patients instantly. These cures were responsible for a brief and faddish detour in the care of the mentally ill known as shake treatments.

Across an ocean, in China, the Manchus prepared for the Year of the Rooster and the end of the female Regency. The power of the Dowager Empress shrank. The influence of the palace eunuchs grew. Neither had much energy to spare for the Celestials dispersed abroad.

In 1873, in the fir forests below Tacoma, Washington, a white woman with short black hair and a torn black dress stumbled into a Chinese railway workers’ camp.

~ * ~

1

The Year of the Rooster

To this World she returned.

But with a tinge of that—

A compound manner,

As a Sod

Espoused a Violet,

That chiefer to the Skies

Than to Himself, allied,

Dwelt hesitating, half of Dust

And half of Day, the Bride.

Emily Dickinson, 1864

The railway workers were traveling from Seattle to Tenino on foot and had stopped, midday, to rest. They hadn’t really made a camp, just a circle of baskets and blankets around a circle of damp dirt that Chin Ah Kin had cleared with his hands prior to building a fire. Chin was briefly alone, although in the distance to his left he could hear the companionable sounds of two men urinating.

It was midwinter, the tail end of the Year of the Monkey and just before noon. There was no snow, but the ground was wet with the morning’s frost and the trees dripped. Underfoot, the fir needles were soggy and refused to snap when stepped upon, which might explain why Chin Ah Kin did not hear the woman approach. It was a mystery. She was just there suddenly, talking to someone, maybe to him, maybe to herself. Her speech had no meaning he could discern. Chin, whose mother had worked as a servant for German missionaries and later for a British family in the ceded area of Canton and briefly for a family of Mohammedans, had been surrounded by foreign languages all his life. People speaking a foreign tongue often appear more logical and intelligent than those who can be actually understood. It is inconceivable that extraordinary sounds should signify something trivial or mundane. But this woman’s speech felt lunatic, and it was cold enough to give Chin the momentary illusion that her words had form instead of meaning, were corporeal. He could see them, hovering about her open mouth.