Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (63 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

It is no coincidence that this is exactly the same process that had overwhelmed Soviet Russia in the decades before the war. Since the opening of the Russian archives in the 1990s it has become increasingly clear that it was the Soviets who were pulling the strings. The evidence for this is now incontrovertible: one need only read the postwar correspondence between Moscow and the future Bulgarian premier Georgi Dimitrov, in which the Soviet Foreign Minister virtually dictates the composition of the Bulgarian cabinet, to see the extent of Soviet meddling in the internal affairs of eastern European countries.

23

From the moment the Red Army entered eastern Europe, Stalin was determined to make sure that a political system was installed here that mirrored the system in his own country. In a conversation with Tito’s deputy Milovan Djilas he famously stated that the Second World War was different from past wars because ‘whoever occupies a territory also imposes upon it his own social system. Everyone imposes his own system as far as his army can reach.’

24

The threat of the Red Army was certainly instrumental in ensuring the establishment of communism across the region – but it was the ruthlessness of Communist politicians, Soviet and otherwise, which took the policy all the way to its logical conclusion. Through the use of terror, and a total intolerance for any kind of opposition, they created not only a strategic buffer between the Soviet Union and the West, but a series of replicas of the Soviet Union itself.

The Resistance of the ‘Forest Brothers’

The Communist takeover of eastern Europe was not a peaceful process. Fighting often broke out between Soviet sympathizers and those who sought to resist them, workers rioted in response to Communist brutality and peasants armed themselves against the new authorities in order to oppose collectivization. In most cases these were fairly spontaneous expressions of popular anger, and were quickly suppressed. Sometimes, however, a more organized form of resistance grew up.

This was particularly the case in those parts of Europe that already knew what it was like to be in thrall to the Soviets. In the Baltic States especially, and in what was to become western Ukraine, nationalist movements sprang up whose members were highly organized, fiercely patriotic, and prepared to fight to the death. Unlike their neighbours to the south they were under no illusions about Stalin’s intentions. Having already suffered Soviet occupation at the beginning of the war, they did not regard the immediate postwar years as something new, but rather as the continuation of a process that had begun in 1939 and 1940.

The struggle of the anti-Soviet resistance is one of the most under-appreciated conflicts of the twentieth century, particularly in the West. For over ten years hundreds of thousands of nationalist partisans fought a doomed war against their Soviet occupiers in the forlorn hope that the West would eventually come to their aid. This war would last well into the 1950s, and would result in tens of thousands of deaths on all sides.

The greatest resistance occurred in western Ukraine, where the total number of men and women involved in partisan activities between 1944 and 1950 probably reached 400,000.

1

The situation in Ukraine, however, was immensely complicated and involved elements of ethnic cleansing, as I have already shown.

A ‘purer’ version of anti-Soviet resistance took place in the Baltic States, and particularly in Lithuania, which, according to Swedish intelligence reports, had ‘the best organized, trained and disciplined of all the anti-Communist guerrilla groups’.

2

In all three Baltic countries the partisans were collectively known as the ‘Forest Brothers’. In the proudly nationalist atmosphere that has predominated since the 1990s their exploits have, quite literally, become legendary.

In the autumn of 1944, after the Red Army had swept through the Baltic States, tens of thousands of Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians went into hiding. They did not do so lightly. They abandoned homes and belongings, lost touch with family and friends for long periods and frequently went hungry. Some went to live with acquaintances, moving from place to place every couple of weeks, in order both to avoid outstaying their welcome and to avoid detection. The majority fled to the forests, where they often found themselves living without shelter or adequate clothing. The autumn brought rain, which turned many forest areas into virtual swamps; and winter – particularly the first two winters after the war – was extremely cold in this northern part of Europe. Those who were wounded or fell sick rarely had much hope of receiving adequate treatment.

It would be naive to imagine that everyone who subjected themselves to these conditions did so out of mere patriotism. In 1944 their numbers were swelled by local men trying to avoid conscription into the Red Army, along with others whose past political associations gave them reason to fear the Soviets. Later on they were joined by families fleeing deportation, farmers resisting collectivization or new groups of political enemies of the Soviet Union. But at the centre of these people was a strong, organized core who were dedicated to fighting for democracy and the independence of their countries. Many of them were military men of one sort or another: ‘good soldiers’, in the words of one Lithuanian partisan leader, ‘who are not afraid of laying down their lives for the homeland’.

3

This central group supervised the division of people into military-style units, the digging of bunkers and construction of forest shelters, the gathering of food and supplies and – most importantly - the organization of partisan operations.

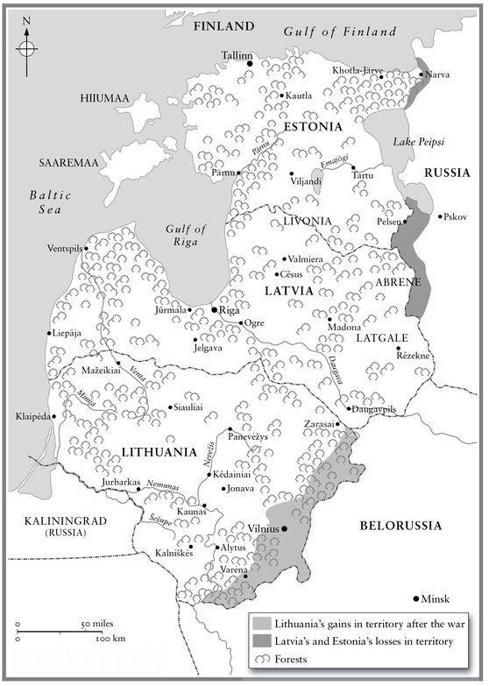

11. The Baltic countries

Right from the beginning, these fearless men and women embarked on some very ambitious operations indeed, especially in Lithuania. In the north-east of the country partisan units of 800 men or more fought pitched battles against the Red Army. In the centre, large groups of fighters terrorized Soviet officials, and even conducted attacks on their offices and security buildings in the centre of Kaunas. In the south they set elaborate ambushes for NKVD troops, assassinated Communist leaders and even attacked prisons in order to free their comrades who had been captured.

There is no room here to give anything like a complete list of the battles and skirmishes that were fought in the first twelve months after the Soviets arrived.

4

Instead I will describe just one, which has, over the years, come to symbolize all of the others. The Battle of Kalniškes happened exactly a week after the Second World War had officially come to an end, in a forest in the south of Lithuania. The battle was between a large detachment of NKVD troops from a garrison in the nearby town of Simnas, and a small but determined group of local partisans led by Jonas Neifalta, code named Lakunas (‘Pilot’).

Neifalta was an inspirational leader, well known in the region for having resisted both the Nazis and the Soviets. A former army officer, he had been on a Soviet hit list ever since their first occupation of the country in 1940. He had been caught in the summer of 1944, and was wounded by a bullet to the chest, but had managed to escape from the hospital where the Soviets had put him under guard. After recovering at the farm of a relative, he and his wife, Albina, had taken to the forest that autumn. They spent the next six months gathering followers, training them, and conducting hit-and-run operations on local Soviets and their collaborators.

Determined to put a stop to Neifalta’s activities once and for all, a large force of NKVD troops marched to the Kalniškes forest on 16 May 1945. They surrounded the area where Neifalta was hiding and gradually began to close in on him. Realizing they were trapped, Neifalta and his followers withdrew to a hill deep in the forest and prepared themselves for battle. They defended themselves heroically, inflicting heavy casualties on the Soviets with small arms and grenades – over 400 of them, according to the partisans themselves (although Soviet forces put the real number at only a fraction of this). After several hours of fighting, however, they began to run out of ammunition. Neifalta realized that their only hope of survival was to try to break through the Soviet cordon. Using the last of their ammunition, two dozen or so managed to burst through the Soviet lines, and escaped to take refuge in the nearby marshes of Zuvintas. They left behind them the bodies of forty-four partisans – more than half their total strength – including Neifalta’s wife, who had died with a machine-gun in her hands.

Neifalta himself lived to fight another day, but it did not take long for fate to catch up with him. That November, in a secluded farmstead nearby, he and his comrades were once again surrounded, and Neifalta was killed in the resulting firefight.

5

When the people of Lithuania remember the anti-Soviet insurgency of the 1940s and 19450s, these are the stories they tell. Such battles have become a symbol of everything the Lithuanians wish to remember about their own bravery and the nobility of their cause.

Looked at objectively, however, the Battle of Kalniškes also demonstrates many of the reasons that such resistance was doomed to failure. To begin with, the Soviets were better supplied than the partisans – it was not

they

who had run out of ammunition. The Soviets also vastly outnumbered the partisans at Kalniškes, as they did in virtually every other battle of the time. While some 100,000 people are thought to have been involved in the Lithuanian resistance between 1944 and 1956 – and Estonia and Latvia boasted another 20,000—40,000 each – this was nothing compared to the millions of soldiers that the Soviets could call on once Germany had been defeated.

6

At a local level this meant that the Soviets could afford to lose dozens or even hundreds of men in a single battle. The partisans could not.

Regardless of how noble or brave we might believe the Lithuanian resistance to have been, their conduct of operations against the Soviets was seriously flawed. While the partisans were very good at hit-and-run raids, they could never hope to match the strength of their enemies during a pitched battle. The Battle of Kalniškes is a perfect example of what happened when such groups were forced to fight on Soviet terms. A much more sensible way to fight would have been to split into small groups, only coming together just before an attack and then dispersing again – and indeed, these were the tactics that the partisans would later switch to. But until the summer of 1945 they insisted on maintaining large groups of fighters in specific locations. As Neifalta learned to his cost, larger groups were much easier to find, and much easier to destroy.

What happened at Kalniškes was symptomatic of what was going on all over the country: the Soviets were seeking out individual groups of partisans and picking them off one by one. The partisans found it very difficult to resist this, because they had no coordinated strategy at a national level. The national bodies who had guided them in the early days were wiped out by the Soviet secret police in the winter of 1944-5, and attempts to reunify the resistance did not materialize again until 1946. Local partisan leaders like Jonas Neifalta therefore tended to be isolated: they had very little contact with leaders in other districts, and fought for purely local objectives. Coordinating their actions with other groups of partisans on a large scale was impossible.

The desperate last stand at Kalniškes was therefore symbolic of all kinds of failings on the part of the resistance: a lack of resources, a high casualty rate, flawed tactics, and an absence of any coherent, nationwide strategy. The only advantages they had over their attackers were their passion for a cause worth fighting for, and their fanatical courage. Such qualities should not be underestimated, however, especially when it comes to their capacity for inspiring future generations of resisters.

As for Jonas Neifalta himself, he too was symbolic of both the partisans’ bravery and their flaws. He inspired his followers by leading from the front, and shared all the same dangers and hardships as his men. This was not a style of leadership that was designed to last very long: Neifalta outlived his fallen comrades at Kalniškes, but only by six months.

The Soviet campaign against the partisans was every bit as efficient, and every bit as ruthless, as their seizure of political power in eastern Europe. It had to be. The Soviets were extremely concerned about both the extent and the determination of the resistance they encountered in Lithuania. In the early days their main priority had to be the war with Germany, and they simply could not allow a partisan war to disrupt supply lines to the front. In 1944 the head of the NKVD, Lavrenti Beria, ordered Lithuania to be cleared of partisans ‘within a fortnight’, and dispatched one of his most trusted subordinates, General Sergei Kruglov, to tackle them.

7

Amongst the troops Kruglov had at his disposal were the special units who had just finished conducting the mass deportation of the Crimean Tatars to Kazakhstan.