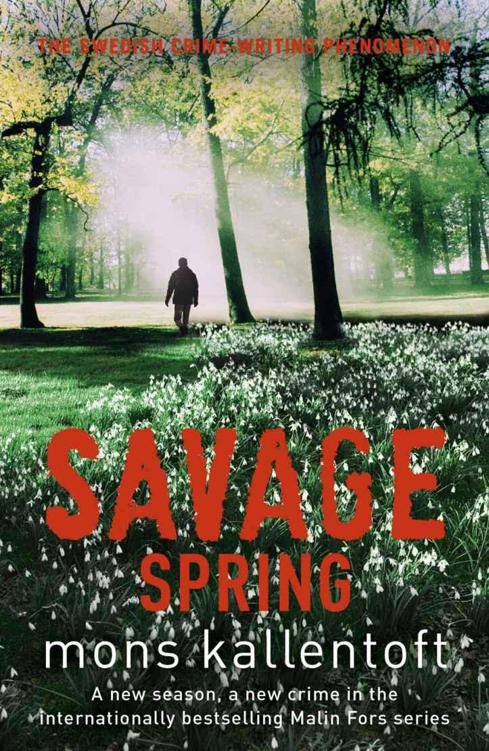

Savage Spring

Authors: Mons Kallentoft

Tags: #Police Procedural, #Crime, #Women Sleuths, #Sweden, #Mystery & Detective

Table of Contents

Also by Mons Kallentoft in the Malin Fors series

Part 2: Out of the black, into the white

Also by Mons Kallentoft in the

Malin Fors

series

Midwinter Sacrifice

Summertime Death

Autumn Killing

SAVAGE SPRING

Mons Kallentoft

Translated from the Swedish by Neil Smith

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Originally published in Swedish in 2010 as

Vårlik

by Natur och Kultur

Copyright © Hard Boiled Company Limited 2013

English translation © Neil Smith 2013

The right of Mons Kallentoft to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

eBook ISBN 978 1 444 72169 0

Book ISBN 978 1 444 72167 6

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Prologue

May 2010

In the chamber of darkness

Where are you, Daddy?

You’re supposed to be here with me.

Where have you gone? Daddy, Daddy, you need to come now.

Little brother’s crying.

He’s so little. He’s lying on the floor, crying, and there’s pee on the floor, Daddy. There are spiders here, and can the snakes get in? The lizards, the great big lizards with yellow teeth, is that what’s making that scratching noise? It’s your fault if we die, Daddy.

He says it’s nasty, nasty.

Like in the pool at home, Daddy. He never dared to jump in, not even with armbands on. I dare. I’m brave. I’m braver than him, because I’m six and he’s only three, nearly four.

I’m sweating and it’s too hot. But only sometimes. I’ve taken my top off, am I allowed to? Now there’s that noise again and I can hear the men coming, Daddy, the light under the door disappears, there’s a ticking sound and everything goes completely dark, and now little brother has to keep really quiet, otherwise they might hit us, and I get scared and I shout:

‘Don’t hit me, don’t hit me,’ and then the light under the door is back and the men go away, I can hear it, but they’ll be back soon, and will I be dead then? Are they going to kill us, Daddy?

We’re locked in, and I want them to let us out. They bring us food, we’ve got a potty, and we’ve been given crayons so we can draw things on the walls and floor. We can’t see what we’re drawing, but we carry on anyway.

I’m frightened. Little brother’s even more frightened.

What’s that ticking sound? Where are those horrid lizards? They shimmer in the dark.

It’s horrid being frightened. I give little brother a hug and he’s all warm and he’s crying, and this is the nightmare I never wanted to talk about. Is that why this is happening now, Daddy, because I never talked about it?

If you’re kind, then everyone is kind back.

Like you, Daddy, you’re kind, aren’t you, you must be kind, and I let go of him and bang on the locked door, shouting:

‘Don’t come back. I don’t want to be dead. We don’t want to be dead.’

Hurry up and get here.

Six Years Earlier

My body is screaming to feel unconditional love and forgetfulness bubbling through its veins, that’s all it wants.

This feeling of feelings is my only desire, the only thing I want.

You have been taken from me.

That’s the way I want it, no one knows about you. I will leave you with what I hope are nice people.

You weren’t even supposed to exist, and then there were two of you, and I look around the hospital room, and see how the pale, dead light of the Stockholm spring X-rays its way across the speckled linoleum floor, trying to drive me away from here.

I shall leave you now, forever, I shall give you up, and you will never have any memory of me, and who your father is doesn’t matter. Maybe I was raped, lying unconscious in some emergency hostel, or in the steel-blue light of one of the toilets in the central underground station, or perhaps someone decided to help themselves in one of the unknown underground chambers where I fell asleep in the wonderful afterglow.

But one day you were inside me. And now you’re in the next room, about to meet your new mother and father, and I feel like screaming, but it has to happen, I want to be somewhere else, love has no place for me and you shall be my great, overpowering secret.

You father could be anyone.

So never ask that question.

Now the door to my room is opening, I see you and you are the only beautiful thing on the planet, never forget that. Now you’re crying, is the light too harsh? And you lie in my arms, I get you to sleep, take the time you need, the midwife says, take what you need, and then she takes you again and I cling onto the bed and weep, but it’s best this way, best this way. And you’re gone, but you should know that Mummy loves you.

The Karolinska University Hospital smells of death and bacteria that no antibiotics can touch, and I tip myself out of bed, pull on the clothes hanging in the cupboard, then shuffle off down the corridor towards the lift, making sure that none of the hospital people see me, because they’d try to stop me. But no one sees, because I know how to make myself invisible.

I don’t feel any guilt, or shame.

Do I? There’s no point thinking about it.

I miss you so much. And I can’t resist, don’t want to.

Soon I’m sitting in a taxi, it drops me at Sergels torg in the middle of the city, and, with a crumpled thousand-kronor note in my hand, I pay a visit to a black man I recognise, I know how to make my way down into one of the central underground station’s most distant tunnels, I borrow the necessary equipment from one of my peers: a flame and a needle later, and the world becomes what it always ought to be, an open embrace free of jagged emotions.

An hour later I’m standing in Hötorget in the suffocating afternoon light. Surveillance cameras everywhere. Watching me.

I see two girls, maybe seven years old, running across the black-and-white paving towards the windows of Kulturhuset, I see their reflections in the glass but I can’t make out their faces. I turn around. Clusters of people, some of them nodding in my direction, as if to say: ‘So, you’re back.’

I nod.

Turn around again.

The girls are gone.

Swallowed up by their own reflections.

PART 1

Avaricious Love

1

Linköping, Monday, 10 May

It’s almost possible to see your reflection in the sky, it’s so explosively radiant and blue.

It’s the same colour as the very core of a welding flame, the mother thinks as she walks across the cobbles of the main square, so closely packed together, fused by thousands and thousands of human footsteps, people wandering back and forth in pursuit of what they want out of life.

The sun is low in the sky, its rays piercing the atmosphere like shining, sharp, steel spears before burning the faces of the people sitting under the huge awnings stretched out above the terrace cafés of Mörners Inn and the Central Hotel. A meagre warmth, with the chill of winter still encapsulated deep in its heart.

The mother looks over at the building containing the estate agent, and can just make out the desperate adverts in the windows. She notes that there’s no queue at the cashpoint, and she looks up at the clock beneath the eaves, the steel hands look as if they’ve been fixed into position, but she knows they can move.

Quarter past ten.

Empty shop windows on all sides of the square. Boutiques and cafés that have had to close in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The signs announcing slashed prices and clearance sales remain, and seem to plead for people’s attention through the fine pollen dancing in the air.

There are surprisingly few people about, she thinks, no market stalls today, no farmers in from the plain trying to sell organic vegetables grown under glass, no immigrants trying to sell fruit for cash, no second-hand stalls trying to charge ridiculous prices for knick-knacks that should have gone to the dump years ago.

But the hotdog-seller at the corner is there. He’s huddled under his orange, yellow and red parasol, waiting for hungry passersby to stop for a morning snack and fill their stomachs with the low-price alternative he can offer.

Ten kronor for a hotdog. And the flowerstall is there, selling tulips in shades of pink, yellow, red, and orange.

The children, the twins, the girls, are six years old now, running ahead of her, over towards the SEB bank, towards the cashpoint where she usually takes out money before they do whatever chores need doing. Matching pink jackets, matching jeans, white trainers with four red stripes on each side.

There are two of them, but they live, act, and talk as one, in all things they are one and the same. Often strangers can’t tell the difference between them, and are astonished at the liveliness, gaiety, and beauty that the girls radiate, as if their whole existence were a hymn of praise to the fact that the world exists and they themselves are allowed to be part of it.

Their blonde hair is ruffled by the wind, their bodies move fluidly, yet simultaneously jerky and slightly awkward, a sign that there is still an endless amount to discover, both in their own bodies and in the whole of the universe, which at this moment, in this square, in this provincial city, belongs to them.

The mother breathes in the spring air.