Scattered (31 page)

It wasn't that Vicki didn't want to be a better motherâof course she did. But she also wanted to keep partying, she wanted to press ahead with her 60-hour-a-week career âeven though it was killing me', and she wanted to take some time away from Mark. Not all of these desires were compatible. She told herself that she'd had sex with Peter as a way of bringing things to a head, an avenue for telling Mark she wanted a separation. And maybe things would sort themselves out with a bit of space.

She was keenly aware that it was a bad look, however, for a mother to have left her children, even if temporarily. So guilty was she that Vicki dropped out of contact with her parents. A tight-knit family group, their interest in her circumstances offended her sense of privacy and alienated her from them. They talked a lot with Mark and swallowed his side of the story, which only made Vicki resent them and guard herself more zealously.

She knew she was messed up, but this was a necessary phase of self-discovery, she thought. She'd be better for it. She took out a short-term rental on a serviced apartment and saw the kids most weeksâduring the week, rather than on weekends, which she spent with Peter and the young skateboarding guys.

By now, Vicki was only straightening out from the past weekend on Wednesday, and by Thursday she and Peter would be arranging deals. Sometimes they'd have an early start for the next weekend. Life was a weekend. Wednesday was her âCFD'âcrystal-free day.

It sounds from this distance as if her life was spinning out of control. It didn't seem like that to her at the time, though. âI was quite steady and rational, in my mind at least. I actually thought I was the only person who was being rational, and Mark and my family were the ones who were losing it.'

She and Peter didn't go to parties as much. Vicki didn't want to run into friends or acquaintances and face the relentless questioning over Mark and the girls. She really didn't want to see anyone except Peter. When she smoked now, she liked to stay home and clean, or do paperwork, or watch television, or play the computer games on which Peter was hooked. More and more she saw crystal as an efficiency-assisting medication. She hated wasting her time. Getting high was not an escape from life's mundane tasks, it was a way of making them tolerable and even enjoyable. It wasn't about tuning in and dropping out, it was about work and usefulness. It was a drug of the age.

She liked that it helped her keep her weight down. She heard the stories of girls using it as a weight-control drug to counter the effects of alcohol, âand I guess I was seeing it the same way', she says. âIt was all bound up with me making the best of my life. I was drinking a huge amount, and the crystal was, you know, to offset the alcohol. Peter and I were smoking heaps of dope, too, to take the edge off the crystal and help us come down, but dope has its own after-effects and I'd smoke some crystal to clear my head of the herbal haze. That was how the logic worked. I know it sounds stupid, but everything made sense to us then, as if crystal was helping us on this sort of health kick.'

The initial rush of smoking crystal was still there, but the overall effect over the five or six hours of a high was to normalise her. She was no longer taking it to enhance her already good mood, as she had in the early days with Mark. Now she smoked to push away a negative mood: subdue the jitters, the anxiety, the anger, the self-recrimination. Crystal wasn't making her manic anymore; it calmed her down. âIt didn't take me high; it straightened me out.'

She was using one to two grams a week. It wasn't a big habit in the scheme of things, and the scheme of things was that she knew people who smoked or blasted five or ten grams (who was keeping count? Not her, not them). The scheme of things wasn't as it used to be. Vicki's entire settings of normality had shifted. She had a high-paying job, she had a nice apartment, she drove a Lexus, and she wasn't doing anyone else any injury. She even rationalised her separation from Mark and the girls by this contorted logic of minimising harm. She would have been hurting them more by staying at home and growing increasingly unhappy. So she told herself.

But she also knew she wasn't well. Every morning, the cravingâa kind of hollowed-out stomach, and a headache followed by an intense burst of sadnessâwas what woke her. When she got out of bed, she felt thirty years older, bent by sickness and suffering. By the end of 2005 she was having âa very light smoke' each day before work, preparing a pipe for later, and living for that moment when she could spark up again. The afternoons were a horror show of irritability, paranoia and wild tantrums. Once she caught herself just short of spitting in a workmate's face. She had been reported for abusive language and had lost concentration in meetings, forgetting what had been said and trying to bluff her way through, to the point where questions were being asked about her fitness for a job she'd been doing competently for nearly ten years. They were saying she was âburnt out', but they didn't know the half of it. With Peter one night, she suffered an episode of hyperthermia, growing so hot from dancing repetitively to their home karaoke machine that he was on the brink of taking her to hospital.

He cooled her down with ice packs, and she didn't go to hospital. In fact, Vicki was invisible to the health and justice systems. She was never detected by any kind of research, because she never presented herself for care to a doctor and was never caught in a criminal act and taken to court. Neither Mark nor her parents were among the thousands of Australians who by 2005 were flooding family advice services such as Tony Trimingham's NSW Family Drug Support Service or the Victorian Family Drug Help helpline asking for support in dealing with their son's, daughter's, wife's or husband's ice habit. These services recorded a trebling in ice-related calls in the two years up to 2004 and a fivefold increase up to 2007. Ice had become a family problem.

But Vicki Wolf never came out into the open. Her problem was hers alone.

Then, at the end of 2005, she took redundancy from the law firm. She saw it as a smart move, jumping before she was pushed. Not only had she dropped out of the reckoning for a partnership, she was worried she might be sacked. So redundancy came as a lucrative relief.

None of her problems were her fault, of course. Mark says that this has always been the way with Vicki, even when she's well. Everything is everyone else's fault. But when things were good for them, heâand sheâmade a joke of it.

In December 2005 it was no joke. She told her colleagues that she was leaving work to spend more time with her daughters, to repair her marriage, to live healthier. She had been undermined at workâeveryone else was wrong about her, she was the only one who told the truth. There were just too many hassles anyway. Her reasons were a contradictory mishmash which nobody listened to or took seriously. If she'd gone to her farewell party, hastily organised at a city pub, she might have made a speech that embarrassed herself and the firm. But she didn't. The farewell party slipped her mind. She'd vaguely heard about a party that night, but assumed it had nothing to do with her. When she found out later that she'd snubbed her own farewell, âI blamed my assistant for not making the purpose of the party clearer to me. She told me to fuck off. I guess she was glad not to be my assistant anymore. She looked like she'd been wanting to tell me to fuck off for quite a long while.'

If the passage of ice through Australian society could be traced like a barium meal going through the X-rayed human body, here's what it would look like.

It would start with users in their twenties and thirtiesânot simply the sentinel group of urban injecting drug users, but white-collar middle-class people like Vicki Wolf and Mark Thomas, who first used ice with contacts from south-east Asia, and gay users in the inner cities. It also had a strong foundation in bikie culture. Ice was never simply a blue-collar or a white-collar drug, straight or gay, dance-clubbing or pub-going. It found favour with all socioeconomic and age groups, male and female, urban, suburban and rural, which over time would converge and blur until 70 000 Australians were using it regularly.

But when it was still being used by the first subcultures, in the late 1990s, the next people who knew about it were health workers and law enforcement officials. They in turn passed on their knowledge to researchers like Rebecca McKetin and the other teams at NDARC, who disseminated information in their academic papers.

Wider public awareness didn't automatically follow. The courts became aware of it, families of ice users were affected by it, and the victims of crimes, general practitioners, lawyers, ambulance officers, and unwitting participants in the pseudoephedrine trade like pharmacists were caught up in its side effects.

The mass media awoke in its usual fitful way, alternately asleep at the wheel and running around in a panic like Henny Penny. Media tend to go to the extremes to make a story, and with ice there were two opposing marginal positions: one, that ice was not a big deal, just speed by a new name; and the other, that ice was the new demon drug, a scourge, an epidemic, a threat to children and the future itself.

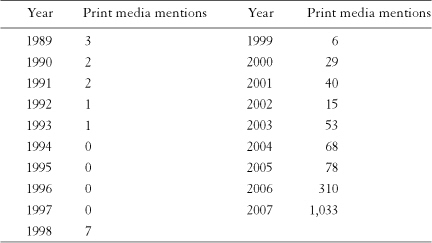

Mentions of ice, methamphetamine and methylamphetamine in Australian print media can be measured. Here is how our media woke up:

At the time Dudley Aslett or Matthew Gagalowicz or most of the most serious offenders detailed in these pages were committing their crimes, it was quite possible, even likely, that the average Australian had never heard of crystal methamphetamine. Only in 2006âironically, when ice use and police seizures had flattened out or might even have been in declineâcan it be said that ice denoted more, in the average household, than frozen water.

Inevitably, once the media woke up, so did the politicians. There had been one or two, such as NSW Premier Bob Carr back in 1998, who had displayed some prescience. But the story of ice, politically, is a good case study of how political action follows rather than leads the headlines. Some state premiers, like Peter Beattie in Queensland (with a typically catchily named âIce-Breaker' strategy) and Steve Bracks in Victoria, were taking action from 2002 and 2003. In Western Australia, where ice hit hardest, it was not until 2005 that the state government stirred itself to effective action. New South Wales only announced a coordinated $400 000 ice strategy, targeting young people, truck drivers, Aboriginal people and the mentally ill, as well as providing clinical guidelines for doctors and emergency departments, in November 2005. Federally, it was 2006 before the then parliamentary secretary for health, Christopher Pyne, made ice his personal hobbyhorse, although in October 2006 his leader, John Howard, rejected calls for a national summit on ice. The following year there was more action on the federal front. The chairman of the peak advisory body, the Australian National Council on Drugs, former Howard government minister Dr John Herron, confessed that âwe didn't realise the real problem', and was soon allocated $150 million to deal specifically with ice. (All up, the Howard government spent $1.3 billion on its drug strategy from 1997 to 2007.) Another federal project appropriated $5.5 million from seized proceeds of crime to be redirected into rehabilitation programs for ice users. Howard himself used a newspaper column in April 2007 to say that the âzero tolerance' approach to heroin, which had âworked so well' in causing the drought, was the template for his government's approach to ice. Meanwhile, the federal parliament, in the form of Senator Bronwyn Bishop's standing committee on illicit drugs, made a priority of investigating the crystal methamphetamine problem and attacked any opponents of âzero tolerance' (such as Alex Wodak). Again, political action seemed to be a dollar short and a day late, and, with a federal election approaching, appeared to have been designed to claim credit for what had already been achieved or to stir up outrage against the already condemned.

In this spread of awareness into the living rooms of suburban Australia, however, there was one particular catalyst, which also says much about the way we learn about ourselves in the twenty-first century: this catalyst was the celebrity ice user.

The first Australian celebrity to be caught using ice was a horse. The Tin Man was a West Australian galloper who tested positive for methamphetamine (most likely injected or ingested orally, rather than smoked) after winning a race at Ascot on 28 October 2000. A long stewards' inquiry ensued, after which The Tin Man's trainer, Hec McLaren, was suspended.

Jokes aside, methamphetamine first came to prominence in the sporting world through the racing industry. American jockey Chris Antley held several riding records and won two Kentucky Derbies, but also endured long struggles with alcohol and illicit drugs. He became a crystal methamphetamine addict in the late 1990s and died in December 2000. More recently, one of New Zealand's top jockeys, Lisa Cropp, who was also successful in Australia, tested positive to methamphetamine after a meeting at the Te Rapa course in May 2005.