Season Of Darkness

Except the Dying

Under the Dragon’s Tail

Poor Tom is Cold

Let Loose the Dogs

Night’s Child

Vices of My Blood

A Journeyman to Grief

Copyright © 2011 by Maureen Jennings

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Jennings, Maureen

Season of darkness / Maureen Jennings.

eISBN: 978-0-7710-4327-7

I. Title.

PS

8569.

E

562

S

43 2011

C

813′.54

C

2010-905272-2

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation’s Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by

McClelland & Stewart Ltd., P.O. Box 1030, Plattsburgh, New York 12901

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925618

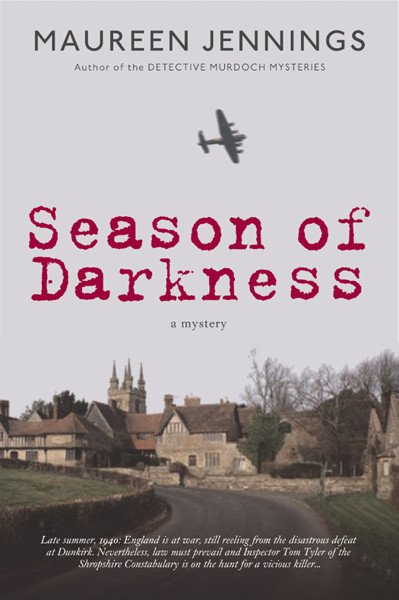

Cover art: houses © Panoramic Images / Getty;

plane © David Fowler /

Shutterstock.com

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

For my wonderful husband and chief supporter, Iden Ford

And also for Thomas Craig, actor par excellence, who

inspired me to create Tom Tyler

“it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness”

Charles Dickens,

A Tale of Two Cities

Prologue

Drawing the chair closer to the table, he sat down and shook a cigarette from the pack. He lit it and took a few deep draws, so that the tip glowed red. He’d already folded the handkerchief, and now he picked it up and stuffed it in his mouth. It wasn’t that he doubted his own resolve, there was no question of that, but he’d learned to accept the body’s instinctive weaknesses and to make allowances. The walls of this house were thin and he didn’t want to risk being heard

.

He raised his bare left arm and studied for a moment the small tattoo just below his armpit. Then, deliberately, he pressed the tip of the cigarette into his flesh and held it there. Sweat broke out on his forehead and he bit down on the handkerchief. When he thought he had accomplished what he needed to, he lifted the cigarette away. The stench of burning flesh was nauseating but he welcomed it. He’d smelled it before and it reminded him that he was a soldier. He spat out the handkerchief and leaned forward, hands on his knees, head bent until his breathing slowed. He allowed one soft moan to come from his lips. Then he took the tin of salve from the table beside him and applied it carefully to the wound

.

He got up, went over to the tiny window, and looked down at the street below. A young woman was walking by pushing a pram. She was pretty in her red and white flowered frock, the early spring sun creating a halo of her fair hair. She bent over the pram, attending to a child he couldn’t see

.

He went to the table where he’d placed a bottle of brandy. He poured himself a tall glass full, picked up his cigarette, and took

another deep puff. He studied the glowing end. Ignoring the gag this time, he lifted his right arm and, with his left hand, pressed the tip of the cigarette against the soft flesh of his underarm

.

He held it there until he could stand it no longer

.

I

N SPITE OF THE FACT THAT SHE’D GOT ONLY A FEW

hours sleep, Elsie Bates was in great spirits. Nothing like a nice bit of dock to make a girl smile. When he’d told her this was his first time, she’d expected him to be clumsy and done too fast, but he wasn’t. She’d helped him out here and there but mostly he’d learned all by himself. Of course, like any man born to Eve, he’d started to show a bit of possessiveness right off the bat, and she’d had to make it clear that nobody owned her. Elsie grinned at the memory, then impulsively pushed down on the accelerator as far as she dared. The sun wasn’t yet up and the road, which was hemmed in on either side by tall hedgerows, was pitch black. She had her headlights on, inadequate as they were with the strips of blackout tape across them, and she was driving as close to the middle of the road as she could, the lorry rattling and shaking on the rough surface.

She started to sing to the tune of the “Colonel Bogey March.”

Hitler has only got one ball

,

Goering has two but they are small

Wait ’til she told Rose about last night. Rosie kept saying she was saving herself, but as Elsie reminded her, “There’s a war on, my pet. Butter’s rationed but that don’t mean we have to be.”

Himmler has something sim’lar

,

But poor old Goebbels has no balls at all

.

Elsie fingered the strap of her dungarees and smiled at the feel of the two bank notes she’d sewn in there. Two quid would go a long way. When she’d told Rose the story, her friend had been nervous.

“Oo, Elsie, be careful. People don’t like to be blackmailed.”

“Who said anything about blackmail? I didn’t say nothing. Nothing at all except to mention what I’d seen, and out it popped: ‘Ow much to keep that to yourself? Didn’t come from me first.” She’d pinched Rose’s thin cheek. “We won’t be greedy. The occasional quid will do nicely. Stroke of luck, weren’ it? Me being there at that moment. Next leave we get, we’re going to Birmingham for a few larks. Nobody’ll wonder where the dosh is coming from. If asked, we’ll say it’s our wages saved up, which is a joke.”

“You’re as cunning as an old cat,” said Rose. “I just hope you’ve got as many lives.”

Elsie had taken the remark as a compliment. She’d learned at too early an age to be that way. You had to if you were going to get out of that bleeding hellhole of a slum in any way intact. She made the sign of the cross over her chest. “May God see fit to drop a bomb on all of them.”

Hitler has only got one ball

,

The other is on the kitchen wall

.

His mother, the dirty bugger

,

Cut it off when he was small

.

The lorry went over a bump, gave a short cough, a splutter or two, then went silent and began to roll to a stop.

“Sod it, not again.”

It was the third time this month the bloody thing had acted up. Elsie managed to steer over to the side, as close to the hedgerow as possible, before the momentum died. The road was barely wide enough for two vehicles to pass, and she’d bring a lot of aggravation onto herself if she blocked the way completely. She tried turning the ignition key but the lorry was dead as a doornail. Sod, sod, and more sod. She was on a tight schedule. She had to pick up the girls at the hostel on time. Miss Stillwell, the warden, could be a bloody tartar. “Late again, Miss Bates? Do pull up your socks, or I shall have to put you on report.” Toffee-nosed old cow. If ever a woman acted like a dried-up spinster, it was her.

Well, no sense in sitting here on her arse. Good thing she’d brought her bike. She climbed down from the lorry. Somewhere along the way her back light had been knocked out, but the front lamp was working. Not that it was a lot of use, with the obligatory taped strips across it.

The woods pressed in close here, narrowing the road even more. Elsie didn’t like the country in the dark. She was used to paved streets and houses crammed together; a sense of the surrounding humanity. You could go for miles out here and not meet a soul. The rooks were putting up a God-awful clamour. Old Morgan had told them that sometimes birds can be as good as a watch dog, giving off warnings that there’s danger near.

She almost wished she’d brought the gun with her.

As she pedalled, she began to sing again to the tune of “Land of Hope and Glory.”

Land of soap and water

Hitler’s having a bath

Churchill’s looking through the keyhole

Having a jolly good laugh

Be … e … e … e … cause

,

Hitler has only one small ball …

She was glad for her overcoat. The pre-dawn air was chill and damp, just a bit of a hint that summer was ending. Fresh though, very fresh; one good thing you could say for the country. Since she’d been here, she gained some weight and a good colour, which they had all admitted when she went home last time. After she’d signed up with the Land Army, her dad, the miserable bugger, had said she wouldn’t last a week, which only made her determined to show him. It hadn’t been easy. When she’d first arrived in Shropshire, she’d never even seen a live cow before, let alone the bloody huge bull with the ring in its wet nose and its enormous goolies hanging down. The work in the fields was backbreaking, the hours appallingly long, and at first many of the farmers had been contemptuous of the girls, not willing to take into account their inexperience. Now the Land girls had earned their grudging respect. They worked as hard as men and learned fast. Elsie, herself, had been promoted to forewoman after only two months. When she’d written to tell Ma and Dad and the others, nobody’d bothered to answer. Sod them anyway.

Dawn was starting to seep through the trees and the exercise was getting her blood flowing. She kicked her feet off the pedals and did a little swoop from side to side just for fun.

Whoopee!

There was something to be said about this war. She’d never have had this experience stuck in the filthy London back-to-back housing where she’d grown up. She kicked out again.

Whoopee!

There was a dance in the village tonight and she’d be there, new frock, new sweetheart.

Hold on, was that a car? Maybe she could cadge a lift. She glanced over her shoulder. She heard the roar of the car as it

emerged out of the darkness, the slitted headlights gleaming like cat’s eyes. It was travelling fast. Too fast. Elsie swerved out of the way.

“Hey, slow down,” she yelled.

But in a moment the car was upon her.

T

OM

T

YLER

, D

ETECTIVE

I

NSPECTOR

, S

HROPSHIRE

constabulary, was having another of his unpolicemanlike dreams. Ever since he’d run into Clare at the market a few days ago, he’d been dreaming about her. Sometimes, they were quarrelling and he was shouting at her, the way he had when she had told him all those years ago she was leaving. Sometimes the dream was unbearably sweet and he was lying with her in his arms. This time, he was trying to find her, running through the empty streets of Whitchurch, calling her name. He’d actually been crying. The pain of that loss was already bringing him to the surface of consciousness when he felt somebody shaking him on the shoulder.