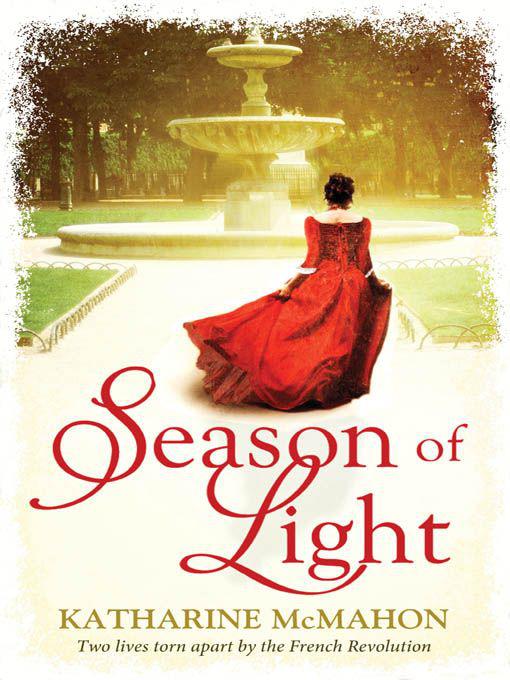

Season of Light

For Martin

Part Three: Compton Wyatt, May 1793

Part Four: Normandy, June 1793

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

A Tale of Two Cities

by Charles Dickens

Part One

Paris, 1788

Chapter One

On the arm of John Morton she floated from the carriage and crossed a courtyard where fountains played amid cravat-sized strips of lawn. A pair of footmen in blue and gold livery bowed them into a marble-floored entrance hall, glossy under the thin soles of her slippers. Double doors were flung wide open, admitting them to a chamber filled with light; suddenly, sensationally, Asa realised that her entire life had been a preparation for the Paris of May 1788.

Sunshine flooded through a dozen windows draped with silk of palest eau de Nil, sparked off the crystal droplet of a chandelier, a gilt-framed mirror, a woman’s earring. Music trickled from a spinet, swagged skirts swayed and merged, and laughter trilled amid a scent of lilies and almond biscuits. Asa’s hand dropped from Morton’s wrist as other conversations faded and there was just one voice, over there by the window; one speaker, to whom all faces turned.

‘Has everyone heard about the events in Grenoble?’ His voice was low but emphatic and the gaze of his sky-blue eyes flashed from one face to another. ‘The people have risen in defence of their magistrates. They have refused to let the

parlement

be disbanded. The king has been foolish in attempting to force through his reforms without the

parlement

’s consent.’

‘Your support of the reforms does you credit, Didier,’ called a woman’s voice. ‘As such a fine lawyer, you are bound to be elected to the

parlement

one day. The old constitution would serve you well.’

‘What do I care about my own future, Madame de Genlis, if I could be rid of this old constitution? I would give everything I have – wouldn’t we all – to serve a new France?’

‘And in Grenoble? What was the outcome?’

‘The outcome was bloodshed, martyrs among the common people, some of whom could scarcely have known what they were fighting for, and casualties among the soldiers brought out to keep the peace. But just think, Grenoble hardly has a reputation as a seat of rebellion – what has happened there could happen anywhere.’

Asa, who had crept to the very edge of the group, was transfixed. Yes, this was it. This was being alive; to be amid people who were actually at the heart of tumult and change. She might have been a million miles from her home in Sussex, where even in the most heated debate at the Abolitionist Society nobody spoke with half such passion. This man, Didier, was vigorous and clean cut. A single slanting gesture from his hand opened a future of infinite possibility. And yet, as he ran his fingers through his unruly dark hair and clapped a friend on the shoulder, he also revealed himself to be boyish, perhaps scarcely older than Asa herself.

‘That’s my brother Didier. I told you about him, remember?’ A touch on Asa’s elbow; Beatrice Paulin, daughter of a professor at Caen university and Asa’s sole connection in Paris. ‘Look at the state of his clothes. He’s a disgrace. If he didn’t spend so much time at the Palais de Justice representing penniless clients who do nothing for his pocket or his career, he might be able to afford a new shirt.’

The sleeves and high collar of Paulin’s coat were indeed shiny with too much wear, his necktie askew as he tugged at it in the heat of the moment, his shoes worn down.

‘What does it matter?’ Asa whispered. ‘What do clothes matter? Surely he puts the rest of us to shame for caring about them at all.’

Meanwhile a young poet had unfurled a scroll with mock solemnity and was reciting a poem entitled ‘Liberty’, lamenting the fact that although the French people had helped to free America from the tyranny of British rule, they still found themselves under the heel of an absolute monarch at home, bankrupting themselves into the bargain. Asa could not help glancing back to the window, where Didier Paulin stood amid a knot of young men deep in conversation. He was at the centre of the group, talking very fast and gesticulating with scholarly fingers, favouring one listener then another with a glance from those astonishing blue eyes. Next time she glanced at him, Asa drew breath sharply, because he had caught sight of her and seemed to pause. She turned her head away abruptly so that a lock of burnished gold hair, in a shaft of sunlight, fell across her breast.

‘Come and meet Madame de Genlis,’ said Beatrice, leading Asa towards their hostess, who was holding court from a sofa near the hearth. Her corsage was of peach and white roses and her frivolous retroussé nose seemed at odds with the brilliance of her wide-set eyes.

‘So this is the little English scholar my dear friend Beatrice has been telling me about. You are most welcome, Mademoiselle Ardleigh. What do you think of our Paris?’

‘I think it is a city of extremes, madame.’

‘Indeed it is. But don’t be deceived by appearances. You might think it would suit some of us very well to rattle through the streets in our great carriages, oblivious to the suffering of those crushed beneath our wheels, but every right-thinking person in Paris longs for change.’

The ladies around her eyed Asa’s narrow waist and vivid complexion as they fluttered their fans in agreement. ‘Take my dear friend the Duc d’Orléans,’ added Madame de Genlis. ‘He may sometimes seem intent only on pleasure, and may not always find the appropriate words, but one shouldn’t be deceived. His was the lone voice that dared tell his wretched cousin, the king, that he could not force edicts on the

parlement

.’

‘Though she would say that,’ whispered Beatrice as she and Asa moved away, ‘since everyone knows the pair are lovers.’

Goodness, wait until I tell Caroline Lambert about all this, thought Asa, and she glanced nervously at John Morton, who had bustled over to them and might have overheard. Thankfully he had other matters on his mind.

‘You will not believe who’s just arrived; a relative of yours, Harry Shackleford. I met him earlier in the week and he said he might be here today. He wished to be introduced to you. If only your sister had been well enough to accompany us.’

‘What kind of a Shackleford is he?’ demanded Asa. ‘I hope he is not from the branch of the family who will inherit Ardleigh.’

‘That’s it, the Shacklefords of Compton Wyatt in Somerset. This is the younger brother, more’s the pity, but then the older is already married, I believe.’

‘Then I would rather not meet him, Mr Morton, if you don’t mind. Perhaps when Philippa is better …’

Too late; the young man, resplendent in coral-pink satin and looking very hot in his high boots and tight cravat, was weaving through the throng towards them.

‘My dear sister-in-law,’ said Morton, ‘may I introduce a young man who is very anxious to make your acquaintance: your cousin, Mr Shackleford.’

‘

Distant

cousin,’ Shackleford corrected, gazing at Asa admiringly. ‘Miss Ardleigh, I can scarcely believe my good fortune in meeting you here in Paris.’

As he bowed over her hand Asa was treated to a glimpse of elaborately dressed hair and a whiff of citrus perfume. Meanwhile Beatrice had faded into the crowd. Oh dear God, prayed Asa, please let her introduce me to her brother before he leaves. ‘Mr Shackleford,’ she said coldly.

He spoke with the drawl of one educated at Eton and Oxford. ‘Delighted to make your acquaintance, Miss Ardleigh. I’m so sorry to hear that your sister is unwell. I had hoped to meet you both here and congratulate her on her marriage.’

Asa made a cursory bow. What right had he, a stranger – no, worse, a usurper – to pretend concern for Philippa?

‘Will you give her my kindest regards?’ he urged, still gripping her hand.

‘If you wish.’

‘How d’you find Paris?’

‘I am fortunate to be here.’ Asa withdrew her hand. Out of the corner of her eye she spotted Beatrice’s sea-green gown and beyond, still by the window, the brother, Didier. Had he noticed that she had been cornered by the most foppish man in the room?

‘And Paris shares your sense of good fortune, Miss Ardleigh. Even had I not met your brother-in-law I would still have known you were in town. Everyone is talking about you.’

Asa lifted her chin. The name Shackleford was anathema to her at the best of times but here, in Madame de Genlis’s radical salon, she felt tainted even talking to him. Everyone must know that the Shackleford wealth came from slavery and this man exuded ill-gotten gains.

‘Mr Shackleford intends to be in Paris for several weeks,’ said Morton, ‘so we shall see a good deal of him, I hope. And then perhaps we shall meet up with him again in Rome. He is travelling. Mostly for pleasure, he says, and the culture. And some business.’

‘Business, Mr Shackleford?’ Asa said. ‘What kind of business might that be?’

‘My father’s business really. He expects me to be the family’s ambassador whilst I’m in Europe.’

‘And what might you be an ambassador for, exactly?’

Shackleford was watching her cautiously, as if he sensed she was waiting to pounce. ‘Trade. You know. Of various kinds.’

‘Various

kinds

?’

‘What I’ve found very disappointing, Shackleford,’ said Morton hastily, ‘is that so few people in Paris speak English. I have much advice to offer – I should so like to enlighten these fellows as to the merits of a well-run parliament – but I can’t make myself understood. I have to rely on my dear sister-in-law here.’

‘Mr Morton tells me you are quite the linguist, Miss Ardleigh,’ said Shackleford, still with a dewy-eyed look of fascination. ‘Now that I admire. My own French is stilted, my German and Italian worse.’

‘I am lucky to have had an excellent teacher since I was eight years old.’

‘Do you read in French?’

‘I do.’

Both Shackleford and Morton were regarding her as one might a performing dog. ‘And which is your favourite novel, Miss Ardleigh?’ said Shackleford.

‘At the moment, Goethe’s

Werther

, of course. Isn’t that the answer you’d expect of any young woman at present, Mr Shackleford? But I am also reading the Abbé Raynal.’

His brow lifted. Good, her comment had hit its mark. He could not be quite so foolish as he looked if he recognised her allusion to a writer who had made a scathing attack on the practice of slavery.

And then all other thoughts were driven from her head because Beatrice approached, gripping her brother’s hand. ‘Here is Mademoiselle Ardleigh, Didier. Her teacher in England is our father’s dear friend Mr Lambert. Do you remember, he stayed at our house in Caen when we were children?’

Paulin’s unpowdered hair was held back by a crumpled ribbon and his blue gaze concentrated on Asa as if the rest of the room were an irrelevance. ‘You need no further recommendation, mademoiselle, if you are a friend of Monsieur Lambert.’ His lips had a distinctive upward tilt at either end so that he seemed on the verge of laughter. Minutes earlier, as she had watched him talk about Grenoble, Asa had thought him impassioned and serious, but now there was a lightness to his voice and smile that was somehow heart-rending by contrast.