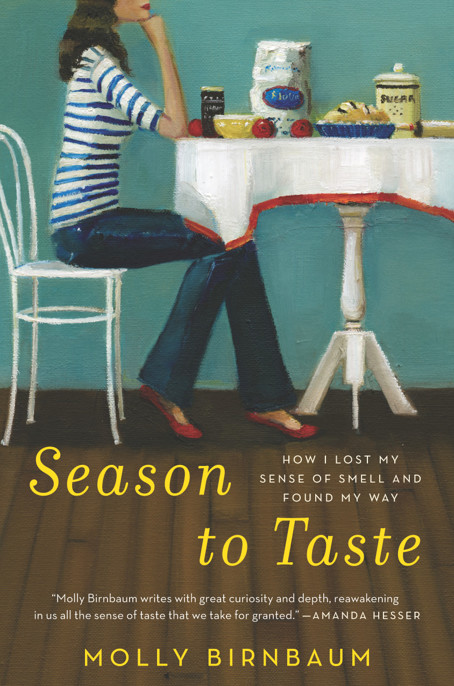

Season to Taste

Authors: Molly Birnbaum

season

to

taste

HOW I LOST MY SENSE OF SMELL

AND FOUND MY WAY

molly birnbaum

Dedication

for my family

Epigraph

. . . smell and taste are in fact but a single composite sense, whose laboratory is the mouth and its chimney the nose . . .

—JEAN ANTHELME BRILLAT-SAVARIN,

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF TASTE

Contents

Chapter 1 - Duck Fat and Apple Pie

Chapter 2 - Sour Milk and Autumn Leaves

Chapter 3 - Rosemary and a Madeleine

Chapter 4 - Fresh Bagels and a Boyfriend’s Shirt

Chapter 5 - Cinnamon Gum and Sulfur

Chapter 6 - Pink Lemonade and Whiskey

Chapter 7 - Key Lime and Lavender

Chapter 8 - Opoponax and Cedarwood

Chapter 1

Duck Fat and Apple Pie

IN WHICH I ENTER THE KITCHEN

INSTEAD OF WRITING A COLLEGE THESIS,

I read cookbooks in bed. I flipped through culinary magazines and food memoirs, burying my head in the biographies of iconic chefs until the early hours of the morning. After obsessively researching recipes online, I kneaded bread dough on my kitchen counter and assembled fat cakes layered with fruit and cream. I cooked intricate Middle Eastern tagines and watched chocolate soufflés rise slowly in the oven. I was studying for my bachelor’s degree in art history, but in my final years of college I thought of little but the stove. I knew what I wanted: to be a chef.

Once I baked a different apple pie each week for months, feeding an ever-changing group of friends with plastic forks and knives in a cloud of cinnamon and butter, until I perfected the recipe. As a result, I won a small scholarship to the Culinary Institute of America, the finest school for aspiring chefs in the country. I wanted to escape term papers and deadlines, Michelangelo and Gauguin. I wanted to master the formal technique of boning a duck, chopping a carrot, and curing a cut of pork. The only thing standing between me and my starting date at culinary school was the required experience in a professional kitchen.

Upon graduation, I returned to my hometown and moved in with my mother and her boyfriend, Charley. After days scouring the Internet for job listings, I picked one of the best restaurants in the city. The Craigie Street Bistrot, a pint-sized establishment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was housed on the ground floor of a large apartment complex on a residential street near Harvard Square. I walked down a set of stairs to the dark-paneled entrance, opened the door, and poked my head inside. The dining room was light and airy. The scent of roasted chicken, which I had noticed as soon as I stepped out of my car in the parking lot, filled the room. A young woman was arranging flowers in vases.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m here to apply for a job.”

She smiled, but didn’t look up from the bouquet of lilacs. “As a server?” she asked.

“No,” I said, closing the door behind me. “In the kitchen.”

She glanced at me, taking in my white button-down shirt and heels. In a manila folder under my arm, I had my résumé and cover letter, which outlined volunteer work in Africa and cashier positions at late-night undergraduate eateries but held nothing close to the scramble of a line cook over the stove. She said she would get the chef, gesturing to a table in the empty dining room, which looked naked without people or plates. I sat.

Tony Maws, the executive chef and owner, emerged from the kitchen a few minutes later. He wore a stained chef’s coat and fat black clogs; a long and frizzy ponytail snaked down his back. His nostrils pointed upward in his sharp-edged nose, highlighting a set of deep brown eyes. Known for sourcing his ingredients from local farms and a rabid enthusiasm for “nose to tail” cooking, or the use of every part of a whole beast, including the unsavory offal bits like the thymus gland or stomach, Maws had just been named a “Best New Chef” by

Food & Wine

magazine, one of the greatest honors for a rising chef in America. I stood and we shook hands. He glanced at my résumé and raised his eyebrows.

“You have no experience?”

I shook my head.

“And you went to Brown?” He looked skeptical.

I remained silent.

“How serious are you?” he asked.

“Incredibly,” I said in a voice that surprised me with its volume. He stared at me. I didn’t blink.

“Okay,” he said. “But you’ll start from the bottom.”

He meant as a dishwasher. Maws promised that if I could handle the dishes, in all their oily, stinking glory, then he would teach me to cook—and not in the casual, dinner-party,

Gourmet

-magazine style. He would teach me how to handle a knife, wrestle a vat of chicken stock larger than my torso, and clean pounds of wild mushrooms in buckets of water, removing dirt from their knobby contours, bathing in their scent of liquid earth. I could never abandon the sink and the dishes, but in our ephemeral free moments I could learn How To Cook.

ON MY FIRST DAY OF WORK,

I paused inside the walk-in refrigerator. The heavy metal door thumped shut behind me and I inhaled the sharp scents of garlic and onions, vinegar and salt, fillets of tuna and grouper. A lamb carcass hung from the ceiling, sinuous and pink. A vat of chicken stock cooled on the floor. Four bins of fresh specialty herbs were perched on a corner shelf waiting to be plucked, their exotic labels—lemon thyme, anise-hyssop, Moroccan mint—reminding me how far I stood from my mother’s suburban garden. I longed to touch the produce.

It had only been two weeks since I’d donned a cap and gown to receive my undergraduate degree. At the restaurant, wearing the uniform white-buttoned shirt and a bandanna tied tightly around my curly hair, I was surprised to find myself in a world that didn’t involve laptops or cell phones, one where I couldn’t sleep when I liked or lose myself in the silent recesses of the library hour after hour. It didn’t involve much thought or speech, only movement and speed. It was a world filled with boxes of foraged forest mushrooms, stacks of chocolate bars from Venezuela, and plates of quail so carefully assembled that they arrived in the dining room looking like works of art. There were knives so sharp I didn’t feel the slice on my finger until blood began to run down my hand. There were sauté pans so old that they no longer dented when the volatile head chef slammed them against the counter. There were eleven-hour shifts and sweat soaking every inch of cloth on my body.

I started with the herbs. The restaurant had dozens of organic herbs delivered to the kitchen each morning. There were familiar ones like basil, rosemary, and thyme; and then there were the exotic ones, ranging from pineapple mint to Syrian oregano. They were delivered from a local specialty farm, tied in tiny bundles and labeled by hand. It was my job to clean and pluck the jumble of leaves and stems and have them ready for dinner service. I bent over the tiny metal table in the back corner of my workspace—a crowded hallway in the shadows of a staircase—and pinched my thumb and index fingers over the rough branches to release as many leaves as possible. Each herb left its scent printed on the tips of my fingers. There was the calm, woodsy odor of rosemary and the cool tang to mint. They blended into a mash of forest green that reminded me of trips to the plant nursery with my father when I was young.

“The most important thing, Molly,” Maws repeated constantly, “is that you know the ingredients. If I hold up this chicory flower, you need to identify it in one glance. If I blindfold you, you need to know it as soon as it hits your tongue.”

I painstakingly cleaned and tasted the herbs whenever I wasn’t swamped at the sink with piles of dirty dishes. I tested myself constantly. I discovered that breathing through my nose, slowly and conscientiously, was the best way to understand the intricacies of such subtle flavor, which, Maws insisted, was the only way to become a chef.

One night in the small kitchen I watched from my perch at the sink as Maws prepared to butcher a thirty-pound fillet of tuna in the back hall. He held a long glistening knife, grasping it tightly by the handle with the sharp edge horizontal to the ground. He brought the blade sideways to his face and pressed his nose against the metal, sliding the knife slowly, painstakingly lengthwise. His nostrils flared with each breath.

He even smells his tools,

I thought.

It’s how he understands

.

I didn’t spend my time with many knives at the restaurant. Instead, I was at the sink, spraying grimy sauté pans with the water nozzle. I constantly scurried to and from the bin where the servers wearing immaculate black aprons tied around their waists dumped the dirty dishes, lugging large stacks of plates to the electric sanitizer in the kitchen. I strained chicken stock and pulled delicate skeletons out of hundreds of fresh, glassy-eyed sardines. I stuck my hands into countless buckets of water and wild mushrooms—black trumpets, hen-of-the-woods, morels—to clean the slippery clouds of fungi. I sorted bunches of bright green arugula for the

garde-manger,

the line cook whose job was to make cold appetizers and dessert, and delivered them to his station, which always smelled of burnt sugar from the torched tops of his crème brûlée.

It wasn’t easy. My arms shook with the strain of unaccustomed weight. My legs bore welts from hot sprays of oil, and my neck was constantly swathed in a thick layer of slime, the liquid detritus that clung to my body from the sink, from the fridge, from my late-night cleaning of the deep fryer. Maws expected perfection, and I was terrified of making mistakes. He exacted the best, though, and I spent my every moment in the kitchen watching. He moved with confidence and economy; butchered meat with swift, clean swipes of his knife; and could sear perfect fillets of fish using only the sound of its sizzle to gauge its progress. Maws plated soft poached grouper on an electric green sauce made from sorrel, scattering orange nasturtiums over the top like a painting. His flavors were bold, his concentration intense, and critics sang his praises. Only open for two and a half years, the Craigie Street Bistrot had already been named “One of 5 Best Restaurants in Boston” by

Gourmet

magazine and the “Best French Restaurant” by the

Boston Globe

.

One late night in August I forgot to close the door of the refrigerator that held all of Maws’s confits, the slow-cooked cuts of meat cured in oil or fat. At Craigie Street they were mainly an array of heartier parts: chicken thighs, lamb and duck tongues, and hunks of pork belly, which I had already spent hours pulling apart that night, my arms submerged to the elbow in buckets of slick yellow fat. When a sous-chef discovered the door wide open two hours later and told the chef, I watched Maws’s jaw clench. The contents of the fridge were—

thank God,

I thought—fine. But I could have ruined thousands of dollars’ worth of food. My hands were shaking as I approached to apologize. I braced myself for the chef’s voluminous, vocal anger. But instead he just looked at me for a moment, his gaze level and serious.

“This is a restaurant, Molly,” he said. Disappointment dripped from his voice.

My guilt hindered my movements for the rest of the night, clumsily cleaning heads of garlic for hours in the back. At 1:30

A.M.

, after we had finished dinner service and my fellow dishwasher, Santos, and I had completed cleaning every crevice of the now empty kitchen, I heard Maws call from his office.

“Molly, come here for a second.”

“Yes, Chef?”

I came running.

“One of the trash bags split in the trash compound outside,” he said casually, not looking up from the papers on his desk. “We seem to have a maggot problem.”

Oh, shit,

I thought.

“There are three five-gallon buckets that are . . . not pleasant. You need to bring them in and clean them.” He smiled. “Now.”

I cleaned out the buckets filled with juice from the torn bags of garbage, stinking of meat and milk and the sour stench of active mold, as the tiny white maggots writhed in the sink.

What am I doing here?

I thought as I scrubbed, breathing through my mouth and trying not to gag.