Secret Societies: Inside the World's Most Notorious Organizations (27 page)

Read Secret Societies: Inside the World's Most Notorious Organizations Online

Authors: John Lawrence Reynolds

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Either as a result of honest ignorance, the organization's extreme secrecy, or an effort to downplay the ’Ndrangheta's power, some observers suggest the group is harmless to non-Italians, and Italians themselves are quick to endorse this perception. Promoting the region as a holiday destination, the Calabrian tourism office admits “you will find no Florences or Venices in Calabria.” Instead, in an act of remarkable candor, the tourism office notes, “Calabrian roads can be brutal, and occasionally they are obstructed by police roadblocks.” The office, which organizes tours of Calabria, promises: “We have avoided planning itineraries in certain inland areas which are virtual strongholds of the ’Ndrangheta, the local Mafia, whose main source of revenue is kidnapping the children of wealthy northern industrialists and hiding them in inaccessible caves in the Aspromonte until astronomical ransoms are paid for their release. It should be said that tourists are never the object of this type of crime and indeed, if you travel to Calabria, you will probably never encounter any of these dangers.”

Reassuring. Of course, you may also enter a Calabrian village and encounter a sight similar to that witnessed by the

citizens of Taurianova, a town not far from Reggio di Calabria, where local ’ndrina first beheaded a councilor who opposed their control of the region, then used his severed head for target practice in the town square. This was not a medieval era act, nor even an event that took place 100 years ago. It occurred in 1995.

In the 1860s, a traveler to Naples arriving by sea noticed that, moments after he handed his boatman the fare, a man appeared at the boatman's side, muttered a word, and received a portion of the traveler's payment before vanishing into the shadows. The same traveler, stepping from the carriage that brought him to his hotel that day, observed a similar incident—a man appeared at the driver's side and inspected the fare before claiming a portion of it. Reaching the door to his hotel room, the traveler paused to watch the porter, whom he had just tipped for carrying his luggage to his room, stop to hand part of the gratuity to another man, as furtive and silent as the first two. That evening, the tourist attended the opera to find men of a similar dress and demeanor, carefully counting the money that changed hands from patrons to ticket seller. When the tourist described these events to an Italian acquaintance the next day, anticipating an explanation, the friend closed his eyes, shook his head slightly, and said simply, “

Camorra

.”

Camorra—the word's origins may lie in the Spanish term for dispute, although today it's more simply translated as “gang”—sprang up as a Neapolitan strain of the same breed of secret society as the Mafia and ’Ndrangheta. Unlike these two criminal branches, Camorra was spawned not within blood-related families but from prison gangs who, released from custody, carried their talent for organization and intimidation to the streets.

Camorra established itself in and around Naples as a paternal organization, dedicated to providing assurance to the citizens and businesses of Naples that they would not be harassed by anyone except, of course, Camorra members in the event that its payments were not received. Mafia families in the

U.S. adapted this ploy during the 1920s, where it became known as “the protection racket.” Members were also ready to settle disputes and offer assistance to poorer families or victims of accidents and disease.

The organization proved as vicious in handling its own members as in intimidating the public, whose income it siphoned. Admission into the order required that newcomers commit a major crime to prove their courage and dedication. The very act of being asked to qualify for Camorra membership represented a crisis, because any man who refused the opportunity to join the group by committing the crime risked signing his own death warrant if his killing became the task assigned to a more courageous and less scrupulous candidate.

Whether they considered it futile to battle the Camorristi or to fulfill its own Machiavellian strategies, Neapolitan government officials not only tolerated the group but reportedly employed it for the government's own ends. For years, Neapolitan jails and prisons were administered and disciplined by the Camorra, and the organization reportedly worked with local police to track down and punish criminal acts carried out by anyone who was not Camorristi.

The group's structure reflects the Mafia's for the most part, with a

capo di Camorra

collecting and distributing payments to several smaller groups made up of second-tier leaders and their soldiers. Unlike the Mafia, however, it appears to shun mystical initiations and procedures.

Like other secret organizations engaged in criminal activities, the fortunes of Camorra ebb and flow. From time to time, crusading politicians claim it has been laid to rest, or so weakened that it is no longer a serious factor. Recent assessments suggest the Camorra consist of over 100 different clans with about 7000 members.

Through much of the twentieth century, the Camorra's principal source of income was cigarette smuggling throughout Italy and neighboring countries, performed with such efficiency that Camorra combined forces with the Mafia to handle

that organization's European drug distribution, an immensely profitable move. This led to a series of territorial battles within the Camorra resulting in an estimated 400 violent deaths and driving as many as 200 Camorra members to the U.S., where they quickly set up gangs to deal in money laundering, extortion, robbery, blackmail, kidnapping and counterfeiting. Despite that flurry of expansion, Camorra remains primarily a Naples-based operation, lacking the mystique and historical fascination of the Mafia.

Yet another Mafia-oriented group germinated in southern Italy, this one in Puglia (often called Apulia in English), the peninsula that forms the heel of the “boot.” Sacra Corona Unita, or United Sacred Crown, began like the Camorra with prison gangs who gathered in remote regions where they could be free from surveillance by central authorities. Headquartered in the port city of Brindisi, the Sacra Corona earned much of its income by smuggling travelers to and from Croatia, Albania, and other countries across the Adriatic. It has never achieved the scale of operations of the Mafia or Camorra, either in Italy or in the U.S.

Had the Mafia remained in Italy, it would hardly have registered on any books other than those dealing exclusively with criminal organizations. Its arrival in the U.S. on the cusp of the twentieth century, and its metamorphosis into a purely American strain of secret society, vaulted it into the public consciousness and secured it a place in popular culture. Everyone in the U.S. knows “Mafia”; few, however, fully understand its structure, operations and influence.

10

Journalists often write La Cosa Nostra, which is grammatically incorrect.

For example, the term “Mafia” is not entirely correct when referring to the U.S. counterparts, whose members refer to their organization as Cosa Nostra, “this thing of ours.”

10

And while

omerta

and other tools to ensure secrecy remain in place,

the American branch has attempted to structure itself as a reflection of U.S. business principles rather than an extension of mystical medieval vows. In the Americas at least, the perceived values of Wall Street carry more authority than thousand-year-old rituals of Sicily.

The first recorded incident of Mafia-based crime occurred in New Orleans in 1891, when a Sicilian crime family murdered the local chief of police, who had been pressuring them with arrests and harassment. The family leaders were tried for murder, but thanks to some witnesses being bribed and others being threatened with death, they were all acquitted. Before they could be released, however, an angry lynch mob shouting anti-Italian slogans stormed the jailhouse, dragged the culprits into the street, and shot or hanged sixteen of them. A lesson may have been learned; while New Orleans has one of the highest crime rates of any city its size in the country, the influence of Cosa Nostra there has never reached the level of other communities, notwithstanding Oliver Stone's claims in his movie

JFK

.

While Cosa Nostra's roots were well established by the end of World War i, two events—one in Italy and the other in the U.S.—propelled the organization into a major force.

The introduction of Prohibition in 1919 created a low-cost, high-demand and high-profit opportunity for criminals, especially those operating within an organization that could manufacture, import and distribute its products under the noses (or with the collaboration) of law enforcement. No other criminal activity promised such enormous profits.

Meanwhile, the dictator Benito Mussolini was rising to power in Italy with the promise of eradicating crime and ensuring that the trains ran on time, among other pledges. He succeeded at both. His fascist administration was the only one brutal enough to threaten Mafia control, and soon many Mafia families were emigrating across the Atlantic, where they joined families reaping massive amounts of money from illegal alcohol.

Northern cities like New York, Chicago, Cleveland and Detroit are most closely identified with Cosa Nostra activities

but more than two dozen communities, as bucolic in nature as Des Moines, Iowa, and San Jose, California, also became operational centers. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 left an intact organization that turned its attention to other illegal means of making a profit. Again, timing was fortuitous for the criminals and disastrous for the public. Two years before Prohibition, the state of Nevada legalized gambling, and on the brink of World War ii, America developed a taste for narcotics. Both events were quickly and efficiently exploited by Cosa Nostra families. By the 1950s, Cosa Nostra was a dominant factor in almost every criminal activity in the U.S., and the major milker of the Las Vegas cash cow, reaping tens of millions of dollars annually from gambling, prostitution, narcotics and the age-old protection racket.

Reflecting strategies perfected by ’Ndrangheta, Cosa Nostra maintained the family structure, although it waived the Calabrian organization's requirement for a blood connection. In fact, it easily overlooked any prerequisite for Italian heritage among its partners, welcoming Jewish and Irish criminals on an associate basis.

While every U.S. city center was placed under the aegis of one or more families, the five families in New York and adjacent New Jersey became the most celebrated due to their power and to the media that covered their activities. The five included these:

BONANNO

: Founded by Joseph (Joe Bananas) Bonanno, the family once was a presence in the garment trade but became deeply infiltrated by the fbi, as told in the movie

Donnie Brasco

. As we'll see, its most recent boss, Joe Massino, has caused the family even more grief than Brasco did.

COLOMBO

: The original boss was Joe Profaci, who ran the family from 1930 until his death in 1963 when Joe Colombo assumed leadership. Colombo was an effective boss right up to the day in 1971 when he was shot at an Italo-American rally. He survived, although he remained in a coma for seven years before

expiring. An extended war developed within the family, with Carmine Persico emerging as the victor until he was sentenced to 139 years in prison for murder and racketeering.

His son, Alphonse (Allie Boy) Persico, is one of the few Cosa Nostra family bosses to secure a college education, where he appears to have majored in wardrobe selection. Allie Boy likes to dress well, even when tooling around the waters of the Florida Keys in his fifty-foot speedboat christened

Lookin’ Good

. One day the U.S. Coast Guard, taking a good look at Persico and his boat, found a hand gun and a shotgun on board. They ordered the guns to be unloaded, inspected the boat, found everything in order, and went on their way.

Allie Boy had lucked out because no one on the coast guard boat checked his criminal record. Only when the coast guard crew returned to port did they learn that Persico had served time for federal racketeering and, banned from owning any firearms, was subject to a ten-year prison term upon conviction. Most college graduates would have tossed the guns overboard as soon as the coast guard was out of sight, but Persico apparently skipped his college classes on logic because, a few hours later when the coast guard cutter pulled alongside the

Lookin’ Good

at dock in Key West, the weapons were still on board and Persico was lookin’ at a decade in the slammer. Lapses in judgment like that one have made Allie Boy such an ineffective boss that other New York families no longer acknowledge the Colombo group.

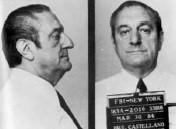

GAMBINO

: This was the infamous John Gotti's family, dating back to the 1920s and named for Carlo Gambino, who ran the family from 1956 to 1976. Gambino, considered one of the most effective family heads (“dons”) in Cosa Nostra, kept a low profile, avoided publicity, stayed in touch with family members, and built the family into a financial powerhouse through narcotics and gambling. In the 1970s he added car theft to the operations, sending stolen luxury automobiles to the Middle East via Kuwait. Gambino's successor, his cousin Paul (Big Paulie) Castellano, alienated various capos including John Gotti and his underboss Salvatore (Sammy the Bull) Gravano, who orchestrated Castellano's murder in 1985. Gotti died in prison, where he was serving a life sentence, in 2001, and Gravano, responsible for a reported twenty murders, entered the witness protection program. Through a series of successions, Gotti's son John Jr. now heads the family.