Secretariat (18 page)

Authors: William Nack

Behind the desk and chair stood a wall of books—volumes of the

American Stud Book, Thoroughbred Broodmare Record,

and

American Produce Record.

To his left, within reach, was the telephone—pale green with three plastic buttons, his instrument of syndication.

The list was his key to it. On it were the names of many prominent owners and breeders, billionaires, millionaires, and six-figure businessmen. There were the names of large and small breeders raising horses for the marketplace, private breeders who raced the horses they bred, old society breeders and newly established breeders and some dependent on the business itself. There were names of well-connected thoroughbred agents—buyers of bloodstock for a wealthy clientele—and names unknown to Seth, friends of Penny’s whom she asked him to call. The list was no tight clique of friends of Claiborne, no fraternity of the inbred elite. What they all had in common, if they had anything in common at all, were mares, money, and a serious interest in breeding and raising thoroughbreds. Socially, financially, racially, and nationally, the list was a mixed bag.

Among the names was the Greentree Stable of John Hay Whitney and his sister, Mrs. Joan Payson; the Rokeby Stable of Paul Mellon, the sportsman and patron of the arts; and the Tartan Stable of billionaire William McKnight, who built the colossus of 3M. From the southwest were Will Farish III, the owner of Bee Bee Bee; Howard Brighton Keck, the oil executive; and Nelson Bunker Hunt, the brother of Lamar and the son of H. L. Hunt, the oil billionaire. Also on the list was the Calumet Farm of Admiral and Mrs. Gene Markey; the Mereworth Farm of Walter Salmon, Jr.; the Darby Dan Farm of John W. Galbreath; and the Fountainebleau Farm of Zenya Yoshida, the prominent Japanese breeder. In Canada there were Jean-Louis Levesque, the insurance millionaire; and sportsman Edward Plunkett Taylor, the father of Canadian racing and a major thoroughbred breeder in two countries. Also on the list were F. Eugene Dixon, who was living on a yacht at the time; the French horseman Alec Head, who once trained for the Aga Khan; the bass-voiced Warner Jones, a breeder and one of Bull’s closest friends since boyhood in Kentucky; E. V. Benjamin, Jr.; the Nuckols Brothers; and Dr. William Lockridge, who carries a clipboard at yearling sales and looks like a high school football coach. Seth would also call Bob Kleberg, whose King Ranch is larger than the state of Rhode Island; Dan Lasater, who began working for sixty cents an hour at McDonald’s when he was seventeen and retired with $30 million at twenty-nine; Mrs. Richard C. du Pont, whose husband was a pioneer in glider aviation; Doug and Mary Carver; Mr. and Mrs. Paul Hexter; Milton (Laddie) Dance; Dr. Eslie Asbury, the Cincinnati surgeon; Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt; and Captain Tim Rogers, who was waiting to hear from Finney. And finally polo-playing Michael G. Phipps, the president of the family’s Bessemer Properties and a cousin of Ogden Phipps; and Ogden Phipps himself.

Ogden Phipps would have owned Secretariat if he’d won that coin toss two and a half years ago, and now young Hancock was asking him to buy one-thirty-second of the colt for $190,000, just $10,000 less than he spent on the debut of his daughter Cynthia.

Hancock had just called Phipps seeking permission to syndicate the horse. As a member of the three-man advisory committee set up to oversee the operation of the farm, Phipps would have to approve the decision. He did. And while discussing the syndication, Seth asked Phipps if he would buy a share. For several minutes they bandied the price about while Ogden hesitated.

“Do you think I ought to go?” he asked Seth.

“Well, Mr. Phipps, Bold Ruler was

your

horse and this is his greatest son. It would be a kind of slap in your horse’s face if you didn’t.”

Bold Ruler raced in Mrs. Phipps’s colors, but Ogden managed much of the stallion’s career as a stud horse, arranging the coin flips and building the bloodstock, and finally, ordering the dying horse put down. At his mother’s death, Ogden ascended to the leadership of the most powerful racing family in America, a family with bands of the finest bred mares in the world and stables at Belmont Park filled with their sons and daughters.

The $190,000 for a share gave him only brief pause.

“Yes, I better go,” Ogden said.

By the time he walked into his office early that February morning, Seth had already recorded Phipps as the first shareholder in the Secretariat syndicate. He was about to start working the telephones when he glanced outside and saw the blue 1973 Fleetwood cruising by. It was seven-forty-five. Dr. William Lockridge eased his Cadillac to a stop near the office, shut off the engine, and picked up a copy of the

Daily Racing Form.

It was a cold morning in Paris, and Bill Lockridge sat bundled against it in his quilted duck-feather coat, pearl gray, waiting for the van that was trailing him from his Walmac-Warnerton Farm in Lexington. Lockridge was a modest but successful market breeder, selling at auction the young horses he bred and raised himself. He was a regular customer at Claiborne Farm, breeding his mares to Claiborne stallions. In fact one of his mares had an appointment with Reviewer, a young Bold Ruler stallion, that morning. The breeding shed opens at eight o’clock, so Lockridge killed the engine and sat back with the racing form. He had fifteen minutes. His eye caught a story about Secretariat. He became engrossed in it.

Lockridge’s opinion of Secretariat had changed considerably since he first saw him in a picture on the front of the

Thoroughbred Record

that past summer. At the time, the photo reminded him of something his New York trainer, Jimmy Picou, had told him earlier. Picou had seen Secretariat run, and he told Lockridge that the colt was a son of Bold Ruler who ran as if distances wouldn’t bother him. When Lockridge saw the picture, when he noticed the Nearco sloping rump and the thick muscles packed along his neck and shoulders, he concluded that he was looking at a Bold Ruler sprinter and nothing more, a prototypical dashman.

Lockridge followed Secretariat closely through the autumn, through the extremely fast mile of the Champagne Stakes, through the stakes-record clocking in the Laurel Futurity at a mile and a sixteenth, and finally through the victory at Garden State Park. And he saw what Picou had seen as far off as Saratoga.

What most compelled his interest in the colt, what made the colt so attractive to Lockridge as a stud horse, was the male line to which he belonged.

Seth Hancock opened the door of Lockridge’s Cadillac, startling the doctor, and slipped in next to him.

“I’m getting ready to start syndicating now. What do you think?” asked Seth, and quoted the price.

“That’s the retail price,” said Lockridge, but he didn’t hesitate.

“Do you want in?”

Lockridge, considering it briefly, was convinced that the red horse would do well in stud, and the better he did the more he would be worth. “This horse had to do well because he was from the most genetically prepotent male line in the history of American thoroughbred racing. That line gets a higher percentage of high-class horses than any other male line in the breed.”

“Do you want in?”

“I certainly do,” said Lockridge.

Secretariat being led to the track at Belmont Park for a workout.

PHOTO: N.Y.R.A.—PAUL SCHAFER

Secretariat, with Jockey Ron Turcotte up, finishes a morning workout at Belmont Park.

PHOTO: N.Y.R.A.—BOB COGLIANESE

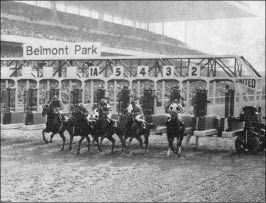

Field of five breaks from starting gate for 105th Belmont Stakes. Secretariat is in #2 post position.

PHOTO: N.Y.R.A.—BOB COGLIANESE

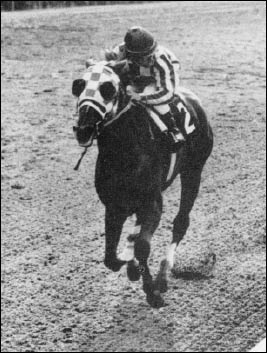

Secretariat rounds turn for last quarter-mile in the 1½-mile race at Belmont.

PHOTO: N.Y.R.A.—BOB COGLIANESE

It was a record that still stands: Secretariat winning the Belmont by 31 lengths in a time of 2:24.

PHOTO COURTESY OF

THOROUGHBRED RECORD

Ron Turcotte checks his record-shattering time as he crosses the finish line.

PHOTO COURTESY OF

THOROUGHBRED RECORD

So the first day has begun, not behind the desk but outside the office, where Seth is shaking hands with Lockridge, climbing from the Cadillac, and ducking back inside to search the world for twenty-six more.

Seth tells Patti Tompkins, his secretary, who is working in a nearby office, to start making calls to breeders at the top of the list, to those Penny has asked him to call, and to those he believes are most likely to buy a share. For he is moving early and quickly to lay a strong foundation for the syndicate, something he regards as essential, playing to the psychology of the marketplace as he understands and anticipates it. He knows the price and the speculative nature of the investment could create conditions for a flourishing stock market mentality, in which what

appears

is as vital as what

is,

and it is imperative to keep up the appearances.

Seth believes that speed is important to ultimate success, that the longer the syndication takes to complete, the more suspicious of the goods becomes the marketplace.

“See if you can get Walter Salmon for me,” Seth tells Patti.

Tan and still vigorous, nearing seventy, Walter Salmon, Jr., has just returned home to New York from Florida, where he has heard that a Meadow Stable syndication is about to begin.

He has already thought about buying a share in Secretariat, anticipating since hearing of Chris Chenery’s death that the colt might have to be sold to raise cash for inheritance taxes. So when Salmon picks up the phone in his Roslyn, Long Island, home—a renovated stable set back off the sound—he knows the instant he hears Seth’s voice that he is calling on the syndication of either Secretariat or Riva Ridge. It is his business to know and anticipate such things.

Salmon’s father started him in the business of raising and selling thoroughbreds more than fifty years ago, and to that work he has applied himself ever since. At the time Seth calls, Salmon is the head of a large and diversified real estate and farming enterprise that fixes his energies on his sixty-story office building at 500 Fifth Avenue and his thirty-two-story office building at 11 West Forty-second Street, both in Manhattan; on his Hiram Walker, Coca Cola, and Canadian Club signs that wink and nod above Times Square; on Saint Thomas in the Bahamas, where he owns 120 acres of land on the top of Fortuna Mia Mountain; and on his 3500-acre showplace of a farm, called Mereworth, in the heart of the Blue Grass country, where his father bred and raised Discovery more than forty years ago. Walter Salmon owns fifty-eight broodmares and breeds and raises yearlings for the marketplace. He runs a major commercial breeding enterprise, one of the largest and most successful in Kentucky, annually dispatching his best bred mares to some of the finest and most promising stallions in America—to Arts and Letters, Damascus, Dr. Fager, Majestic Prince, Nashua, Tom Rolfe, Creme de la Creme, Buckpasser, Le Fabuleaux, Hail to Reason, Hawaii, and Gallant Man. Salmon owns shares in numerous stallions, and he has earned a name as one of the industry’s most active buyers, investing money from his considerable fortune to gain access for his mares to all the most vigorous male lines available in the country.

“And we wanted to know if you wanted a share in the horse,” Seth is telling him.

“What’s the price?” Salmon asks.

“One hundred ninety thousand a share.”

Salmon does not leap into a commitment. He questions Seth on the terms of the contract. He wants to know, for instance, how many other commercial breeders there will be in the syndicate. Salmon always asks this. It is one of his standard questions.

Walter Salmon thinks about it, and then he says to Seth, “I’ll call you back.”

Walter Salmon, vigorous investor in bloodstock, will call back?

What is wrong?

For Seth Hancock this is the first disturbing moment. It is not a refusal, just a hesitation, but it gives him pause to wonder whether something might be whacky in the general American economy, something that would make a financially sensitive man such as Salmon hesitate to check the economic barometer. Seth knows that the thoroughbred breeding and sales industry is robustly healthy. Just a month ago, at the dispersal sale of the late Fletcher Jones’s Westerly Stud in California, the champion mare Typecast had been sold for a record $725,000, a whopping sum to be paid for a broodmare. Business has been booming in the bloodstock industry, yet Salmon is taking his time.

“See if you can get Mrs. du Pont for me.”

Allaire duPont has been a client of Claiborne for many years, a person of taste and financial vitality in the breeding of American bloodstock.

At her 800-acre Woodstock Farm in Chesapeake City, Maryland, she raises thoroughbreds, keeping thirty-five broodmares in the nursery, rides and looks after her great gelding Kelso—five times America’s Horse of the Year (1960–1964), five times winner of the two-mile Jockey Club Gold Cup, and the biggest money earner in the history of the sport, winner of thirty-nine of sixty-three starts and $1,977,896. “Kelly” was foaled and raised at Claiborne.

Seth is depending on Mrs. du Pont to take a share. Lately she has been breeding mares to Claiborne stallions Round Table, Buckpasser, and Herbager, among others, and Seth has her high on the list as a potential buyer for a share in Secretariat. Reaching her at Woodstock that morning, he informs her of the essentials in what has become his standard sales delivery.

“I called because Mrs. Tweedy has authorized me to syndicate Secretariat for her and I’m in the process of doing it right now. We wanted to know if you wanted a share. The price is $190,000 a share, in thirty-two shares, and Mrs. Tweedy is going to keep two under the Meadow Stud and two will be owned by the Chenery Corporation, which is a family holding corporation. The terms are 10 percent down and 40 percent when he passes his fertility test, the remaining 50 percent on January 15, 1974. He’ll continue to race in her colors and anything he might win will go to her.”

After thinking about it a moment, discussing terms with Seth, Mrs. du Pont tells him that

that

is a sizable sum of money to ask for a breeding share and that she would have to consult her accountant before making such an investment. She promises to call him back when she makes up her mind.

Mrs. Richard C. du Pont, an extremely active breeder in the bloodstock market, with close and traditional ties to Claiborne Farm, will call back later?

It

is,

Seth knows, a lot of money, but

not

too much for what he sees as Secretariat’s potential worth as a stud horse. Yet now here are two active bloodstock investors hesitating over a commitment. For Seth Hancock it has suddenly become a discouraging early morning. He is shaken by the turn of things because, if Walter Salmon and Allaire du Pont refuse to buy a share, who

will

buy one? They are supposed to be among the surest, the ones most likely to join. It is as if he is trying to put a twenty-eight-piece orchestra together while the lead musicians are sitting around tuning their instruments. It is especially troubling because time is crucial. Seth soon finds they’re hardly alone.

“People were saying, ‘Well, I don’t know, that’s an

awful

lot of money. I’ll call you back.’ ”

“See if you can get E. V. Benjamin for me,” Seth asks Patti Tompkins.

An old friend of Bull Hancock, a well-known horse breeder and bloodstock agent and the master of Big Sink Farm in Versailles (that’s

Ver-sales,

not

Vers-eye

), Kentucky, E. V. Benjamin is another of the breeders that Seth is counting on to buy a share.

At the moment Benjamin is working in the library of his home, where he has his offices, and he is at the desk when Seth begins to lay out the terms before him, just as he had done with Mrs. du Pont.

Hearing the price, Benjamin blanches.

Benjamin, a successful commercial breeder, has not been a timid spender for shares in stallions. He paid $65,000 for a breeding share in Horse of the Year Damascus, $65,000 for a share in European champion Sir Ivor, $20,000 for one in Drone, and $35,500 for a share in grass specialist Hawaii, all Claiborne stallions. And now Seth is asking him to buy one share in Secretariat for $14,500 more than he paid for those four shares combined. It gives Benjamin pause.

“I paid all kinds of money for shares in horses, but never a $190,000 deal,” Benjamin says.

Benjamin, having been close to Seth’s father, wants to help Seth on his first major undertaking as the president of the farm. But first he has to make some calls, to find others who will share the risks with him.

“I don’t know, Seth,” says E. V. Benjamin, squirming. “I might go, but

that’s

an

awful

lot of money.”

Hanging up, Benjamin asks his thirty-seven-year-old son, E. V. (Tony) Benjamin III, if he wants a share in the red horse. Together they share ownership of Chou Crout, America’s champion sprinter of 1972, a five-year-old mare they are about to retire and send to Damascus. She could be sent to Secretariat in 1974. Tony is noncommittal, so the elder Benjamin turns to sources outside Kentucky, to New York and Ohio, looking for backers to share the cost of a share with him, finding one buyer in New York, a banker. At one point, Benjamin calls Seth back, one of two or three calls he makes during the day to Hancock.

“I’m 75 percent sure,” he tells Seth.

Not much later he calls back again. “Put me down for sure—and with a question mark.”

It is still a cold February morning in Paris, and Seth is discouraged waiting for Salmon and Mrs. du Pont to call, waiting for Benjamin to try to round up support. News that he is syndicating Secretariat has begun to leak out from those he has called, and down in Florida bloodstock agent Jim Scully has heard the rumor and is slipping into a phone booth near Hialeah.

Among others, Jim Scully represents Zenya Yoshida, the leading breeder of thoroughbreds in Japan, the owner of 200 broodmares there and an expansive tract of real estate in Kentucky known as the Fountainebleau Farm. It was Zenya Yoshida’s cousin, Shigeo Yoshida, who staggered the galleries in California when he bid $725,000 for Typecast.

It is past midmorning. By now Seth is taking calls as well as making them, fielding them from all over. Then he hears Scully’s voice. Scully, a wiry, thirty-two-year-old former racing magazine writer, gets 5 percent commission on every dime Yoshida spends on bloodstock in America, 5 percent of the millions Yoshida has been pouring into the purchase of American bloodstock.

“What are you doin’, Seth?” Scully asks.

“Jim, I’m awful busy now.” Hancock has a sense of humor.

“Wait a minute. What are you doin’? I’m here in a phone booth in Miami and there’s a lot of talk goin’ around.”

“What do ya hear?”

“I hear you’re doin’ Secretariat.”

“You want one?” Seth asks him. Scully leaps. “Put me down for one,” he says, “for Yoshida.” Scully pauses, then adds quickly, “Put me down for maybe two. There’s another client of mine who might want one.”

“One to a customer. But if I need any more help I’ll call you.”

At the Big Sink Farm in Versailles, E. V. Benjamin is reaching Susan Proskauer at her home in Akron.

They are old friends, and Benjamin is asking if she would like to be a partner in a share.

Mrs. Proskauer was born Susan Sternberg in Breslau, Germany, and she remembers the day in 1938, at age twenty, when her father took her on a three-hour automobile ride to the base of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. There he put her on skis and watched her escape from Germany. Her parents didn’t survive the holocaust. She later fled Czechoslovakia, when the Axis powers overran it, and finally found her way to America. Her first job was as a maid in Brooklyn, where she learned English, and even today her accent is distinctly German but with a trace of Flatbush Avenue in it. She became a dressmaker in Manhattan, later still a dress designer. In 1945, she married an Akron pathologist, Dr. George Proskauer, and fell in love with Chris Chenery’s Hill Prince in 1950, went into racing herself in the 1950s, and soon was involved in breeding horses. She met Benjamin, who introduced her to Bull Hancock.

“What do you think?” Susan asks Benjamin.

“I think we ought to buy a share,” says Benjamin. She agrees.

Benjamin, with two partners and himself paying a third, dials Claiborne for the third time that day.

“Erase the question mark.”

So the day grinds on for Seth, the first and the slowest of them all, the longest and the most difficult.

He is still waiting for Salmon and Mrs. du Pont to call back. John Finney is still waiting, too, wondering what is going on in the matter of Claiborne syndicating Secretariat. And Tim Rogers and Jonathan Irwin are in Europe, waiting for word on their proposal.

Seth calls the Greentree Stable of John Hay Whitney and Mrs. Joan Payson. He doesn’t talk to Mrs. Payson, though she is a partner in the racing farm and stable. Veteran Greentree Stable trainer John Gaver, who once trained the great Tom Fool, confers with John Hay Whitney on the offer, and Gaver recommends that Greentree decline the share.

“You’re paying a hell of a lot of money for an untried three-year-old,” John Gaver says.

Greentree then calls Seth back. They decline.

Not all breeders are so hesitant as Salmon, Mrs. du Pont, Benjamin, and Greentree. Like Jim Scully, the enthusiasts add a sense of relief to Seth’s day. They are those who buy almost without question, without having to think for hours about it. On that first day the enthusiastic buyers are Milton (Laddie) Dance and Richard Stokes.

They call Laddie Dance at his condominium on a glittering swath of beach in Boca Raton, Florida, where he and his wife Jean, heiress to an Oregon lumber fortune, are spending a part of a winter.

The Dances are only small-market breeders, moving to build slowly upon a band of mares at their 320-acre Taylor’s Purchase Farm in Maryland, but Laddie is well connected in the industry and he has made known frequently his wish to be part of a Secretariat syndicate. He is Fasig-Tipton’s auctioneer, possessing one of those pneumatically deft larynxes out of an old Lucky Strike ad, and a wooden gavel to punctuate his fervent spiel.