Secrets of a Former Fat Girl (6 page)

Read Secrets of a Former Fat Girl Online

Authors: Lisa Delaney

At the end of the period, pick the activity that will work best for you and make a commitment to stick with it for at least six weeks. Why six weeks? That's the length of time researchers say it takes to build a habit. I don't know about that. If everything I ever did consistently for six weeks became a habit, I'd be a checkout girl at Kmart, eating popcorn every night for dinner, and wearing a royal blue LaCoste polo that a boy gave me in the eleventh grade. (I had a crush on him and refused to take it off.)

The six-week thing isn't set in stone, but you'll be doing great to get there. Once you do, technically you should be ready to work harder. Start using that 10 percent rule I explained above and see how you feel. I know that when I was starting out, any deviation from my routineâJazzercise Monday, Wednesday, and Fridayâthreatened to suck me back into the Fat Girl lifestyle. If after the six weeks you feel the least bit precarious, stick with your original program.

Feel free to ignore the fitness experts who suggest switching your type of exercise to keep from getting bored and injured. Not that I want you to be bored or injured. Certainly, if you start feeling symptoms of either, get help. In the case of boredom, that might mean making your workout more challenging or trying something completely new for another six-week trial. On the injury front, stop what you're doing and call your doctor. In fact, that's a good thing for any beginner to do before starting an exercise program, especially if you've had health problems or some other reason for concern.

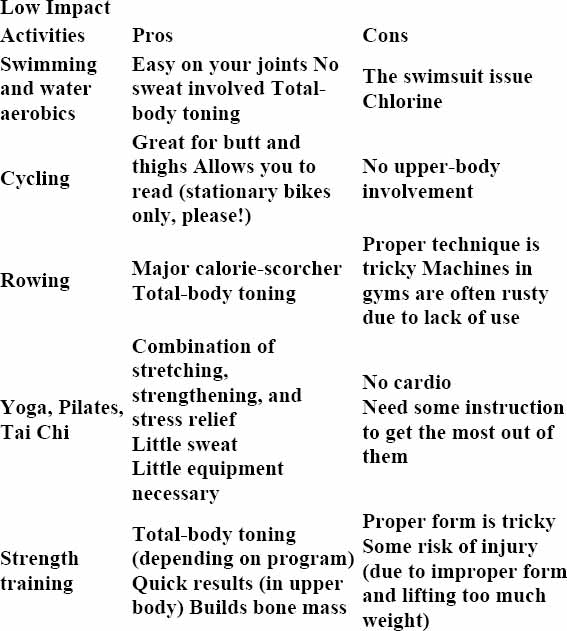

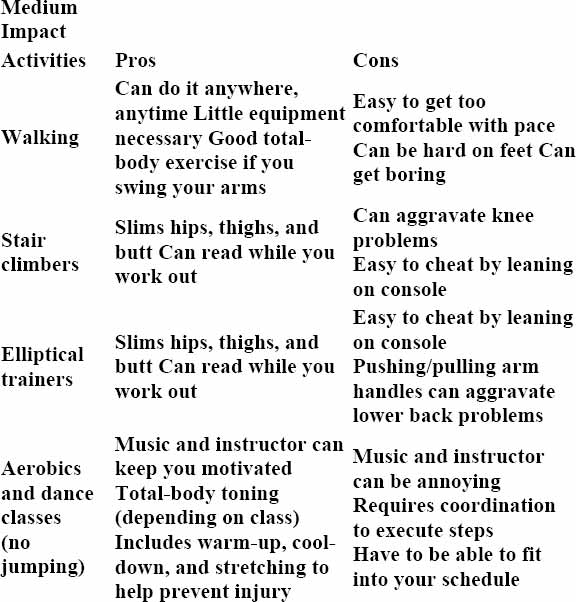

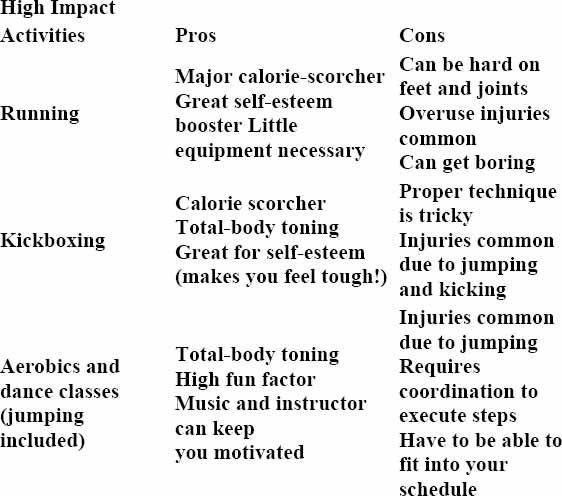

Kinder, Gentler Ways to Get Moving

To help you ease your way into exercise, here's a key to what's low impact, medium impact, and high impact, and the pros and cons of each.

Use the sitcom strategy.

Somehow a thirty-minute workout seems more doable when you realize you're talking about the time it takes to watch a

Will & Grace

rerun (with commercials and credits). What's half an hour in the scheme of things? Nothingâexcept an opportunity to change your whole life.

Eat a taco.

My taco and ice cream workout chaser probably wouldn't be sanctioned by Weight Watchers, but it was a way of rewarding myself for doing something really, really hard and really, really out of character. I'm convinced I needed a reward to keep me going, like I used to reward my dog Yogi for resisting the innate urge to lunge for every squirrel with me in tow on the other end of the leash.

That's exactly what you are trying to do: resist your innate urges and train yourself to behave in a way that doesn't come naturally. So reward yourself once a day for the hard work you're doing. You deserve it. Plus, treating yourself will help keep you in “I can” mode. And it doesn't have to be with food; try a great manicure/pedicure, an hour all to yourself reading at the coffee shop, or the latest chick flick with your girlfriends.

And that's the magic of Secret #1: It helps you lay the can-do groundwork that will shore you up for the challenges of the journey ahead. If you can do this, if you can become the type of person for whom exercise is a habit (and I know you can), you have half the Former Fat Girl journey nailed. I know that without the juice I got from running, I never would have been able to make the transformation. The self-esteem boost, the changes I felt going on inside, spurred me on. Oh, and then there were the calories I was burning with every step.

But as you know, you don't do all this in a vacuum. Secret #2 will help you take on one of the toughest challenges of trying to lose weight in the real world in a way that most diets ignore: the influences of the people around you who unwittingly can keep you stuck where you are. Learning how to stay true to your plan amid all the advice and criticisms meant to be helpful but often anything but, will take you one step closer to making your Former Fat Girl dream a reality.

Secret #2: Keep It a Secret

I

remember the exact moment self-consciousness set in. I was about six years old, practicing for my first tap dance recital in an itchy, yolk-yellow tutu, my poor, bare little thighs jiggling as I shuffled. This was before parents shuttled their kids to a different activity every day of the week. Dance for me and Little League for my brothersâthat was it. With four of us (my sister came along later), that was all the chauffering my parents could handle.

I don't recall too much about the classes themselves, which means they must not have been horrible. But I do remember the nervous anticipation building in the pit of my stomach as the recital approached. It was a big deal, probably the biggest deal up to that point in my young life: We were to perform on a stage, with a curtain and everythingâjust like the people on

Lawrence Welk

, which my brothers and I were forced to watch with Mom and Dad on Saturday nights. I was so excited at the prospect of my star turn that I decided to give a sneak peek of my performance for the family, a decision I would soon regret.

We gathered in the living room of our house in suburban Boston. The relatively bright space with stiff, brocaded furniture and a light sprinkling of fragile knickknacks was typically off-limits to us kids. With the exception of holiday family photos, the living room was adult territory. We spent most of our family time in the basement den where there was a couch comfortable enough to actually sit on and, more important, where the only television we owned was situated.

Every so often my parents would set up card tables in our living room and have friends over to play poker or bridge. I loved it when they entertained, because the next morning I'd sneak down and pick through the scraps on the trays of leftover hors d'oeuvres. Sometimes Mom would leave the nut bowls out when she was too tired at the end of the night to clean up, and I'd scavenge for bits of cashew among the rejected Brazil nuts (which even

I

wasn't desperate enough to eat, at least most of the time).

So when Mom and Dad suggested we hold my private family performance in the living room, I was ecstatic. (Never mind that it was the only room in the house with a stereo, and it had a wood floor that was perfect for tapping.)

Mom and Dad corralled my three brothers into the straight-backed chairs we had set up for the “audience” as I stood on the hardwood floor “stage” in front of them, ready to do my thing. SomeoneâDad, probablyâintroduced me and cued up the music. (I think it was our recital piece, the “Theme from the Pink Panther,” but I'm not completely sure.) I started tapping away, searching for the rhythm, tentative at first, my confidence growing with each tap-tap-shuffle-ball-change. I even started showing off a bit, allowing myself to revel in the attention, sinking into it like a steamy bath on a frigid afternoon, and letting it wash over me.

You'd think I was used to all that attention, being the only girl in the family until my sister came along when I was eight. Not me. I defied the prima-donna, center-of-the-universe stereotype usually ascribed to only-girls. For one thing, I was somewhat of an introvert, so I kind of naturally receded into the background, spending hours reading and creating imaginary worlds in my head. Plus, I was a textbook example of the middle child. I had two older brothers: Henry, the buttoned-up, emotionally distant intellectual; Pete, the mischievous renegade (some would say troublemaker). Charlie, two years younger, was the loving baby (at least to my mom; he would prove to be my antagonist as he got older). Sandwiched in the middle was meâthe peacekeeper, the pleaser, the good girl, the one who didn't want to make any waves. I craved my parents' approval, but I was uncomfortable being singled out for any reason, good

or

bad.

For instance, from a very young age I loved the fact that the family often celebrated my birthday and Pete's on the same day. Pete was two years and two days older than me, and our birthdays often ended up on top of the Thanksgiving holiday (mine is November 25, and Pete's is the 27th). Who could blame my mom for wanting to double up? When other kids would balk at sharing anything on their birthdays, especially at tention, I was happy to make room for Pete. And he wasâisâa natural ham, so he did a great job of creating a diversion.

Although I was comfortable with my place in the periphery, I must have had at least a little desire to step onto center stage. Why else would I be so ready to share my tap dancing talents with my family, especially my brothers, who I knew would be a tough crowd? I had been stung by their teasing before, so I knew what they were capable of. Still, I was willing to take the risk. Actually, I wasn't really aware of how much of a risk I was taking. See, while I might have had the beginnings of a Fat Girl body, I didn't have the Fat Girl psyche yet. Even though I didn't actively seek the spotlight, I wasn't yet fearful of it, fearful enough to hide from it at any cost.

That would all change.

There I was

in my tutu, my stubby feet shuffling to the beat as best I could, all eyes on me. I was prancing, bathing in the limelight, completely ignorant of any imperfections in my step and oblivious to the way I looked as I bobbed along. My parents watched, encouraging, approving. I made it a point to avoid glancing in my brothers' direction; I knew they'd do anythingâstick their tongues out, thumb their noses, moon meâto make me mess up.

As it turned out, I didn't need them to sabotage my performance. I took care of that by myself. All of a sudden, right before the big finish, it happened: My black patent Mary Janes slipped out from under me on the slick floor, and I fellâ

smack

âright on my butt. I sat there a minute, too stunned to cry. I could feel my face burning with shame. My brothers dissolved into laughter, unable to restrain themselves. And who could blame them? This was almost as good as a front-row seat at a Three Stooges show.

My mother lunged to help me up. I pushed her away angrily and struggled to my feet. Dad was yelling at my brothers to shut up as I ran to my room, tears filling my eyes.

There I was, full of myself, performing, putting myself out there (even if it was just for my family). I had allowed myself to shine like never before, and what did I get for it? I ended up on my ass and in tears, the butt of a family joke for years to come.

From then on, the last thing I wanted was to be in the spotlight. I wasn't safe there. I didn't know how to laugh it off. I didn't have the strength to set my jaw, dust off my bruised backside, and try again. Why risk that kind of pain when you can stay in the shadows, on the sidelines, a comfortable, content nobody?

Oh, I suffered through the class recital, of course. I was too much of a good girl to make a stink and quit. During the performance, I shrunk back into the second row, tapping very tentatively, too afraid to let myself go and enjoy the moment. Once the dance ordeal was over, I receded further into my imagination, into my books, into my own little world. As young as I was, I knew exactly what I was doing. No way was I going to give my brothers, my familyâ

anybody

âa reason to laugh at me. I'd show them. I would

disappear

.

It's not like I ever ran away or anything (that's not a good-girl thing, either), but I began disappearing, hiding, emotionally and physically. I simply stopped trying. I stopped trying to be heard in a household of constant noise and interruption. I stifled my interest in any kind of after-school activities. I abandoned any effort to pull myself out of my comfort zone, the safety of my own inner world.

Only part of my motive was self-preservation. The other part was the childish hope that someone would see my pain and rescue me from it. Like the runaway who secretly wishes for her parents to come after her, I yearned for mine to recognize my silent protest. I was trying to make a point, to let my family know (my parents in particular) how much the ridicule hurt me, to shame

them

for shaming

me

.

I actually devised a test for the family, a little game of hide-and-seek. I was the hider; they were the seekers. But here's the trick: They didn't know they were playing. They were supposed to notice my absence and become concerned enough to come looking for me. The problem was that no one ever did. I'd hole up behind one of the burnt orange and gold chairs in the forbidden living room, waiting to hear, “Has anybody seen Lisa? Where could she be?” Instead, the household clicked along without me, never noticing my absence. I'd give it about an hourâwhich seemed like foreverâand then I'd resurface, going back to my books or my Barbies as if nothing had happened, all the while aching inside.

Sad, wasn't it? And I'm just getting started.

I struggled to conceal my emotions, afraid of being teased and laughed at. Crying was a big no-no. I remember when the movie

Brian's Song

was on TV for the first timeâthe story of the pro football player who dies of leukemia after standing up for his friendship with an African American player. A classic tearjerker. Watching the movie in the den with my family, I moved from the couch to the floor as the plot became more and more upsetting. I lay on my stomach with my hands cupped around my face so no one would see my tears. I used that strategy while viewing many a made-for-TV movie over the years.

And God forbid that anyoneâmy brothers or my Dad, especiallyâsuspected me of having a crush on a

boy

. They'd launch into a rendition of “Lisa and [boy's name here] sitting in a tree, k-i-s-s-i-n-g,” or torture me with smooching noises on the rare occasion that a boy actually called me on the phone. In response, I learned to hide those feelings, too. I was embarrassed by them, almost as embarrassed as I was when I slipped and fell that day in the living room.

As I shut out the outside world, my inner world exploded with life. I daydreamed constantly, conjuring up entire relationships and conversations with kids at school or in the neighborhoodâkids I didn't have the nerve to speak to. I lived through my books, diving into the worlds created by the authors. I loved books by Judy Blume whose heroines were often girls like me, girls on the outside looking in. I loved Nancy Drew, because she was so

not

like meâtaking chances, speaking up, stepping forward. I loved Jo in

Little Women

. I wanted to

be

her, the instigator, the driven one, the champion of self-expression. I read whatever I could get my hands on, and when I found a favorite, I went back to it repeatedly, revisiting the characters as if they were old friends.

When I was in fifth or sixth grade, I discovered

Harriet the Spy

by Louise Fitzhugh. Harriet was this little mousy kid, kind of nerdy and supersmart, the underdog protagonist typical of many books for preteens and teens. (Think Hermione from the Harry Potter series, without the wand.) Harriet fashioned herself as some kind of secret agent, keeping notes on the kids and goings-on around her.

Like me, Harriet had a secret life, a life where she could be smarter, more creative, stronger, braver. Where she could be everything she wanted to beâeverything she felt she couldn't be in the real world.

No wonder I related.

I was hardly the only

kid who was ever teased or experienced some kind of spectacular failure. There are millions of them: the directionally challenged peewee football player who scores a touchdown for the other team; the unfortunate girl who is caught without a pad when she starts her period and everyone can tell (by the way, that happened to me, too); the stomach virus victim who pukes on her desk during second period (uh, me again). There are certainly worse things that can happen to children, that

do

happen to children. All you have to do is watch one of those twenty-four-hour news channels to know your place in this sad spectrum. The blooper reel of my childhood is nothing compared to what some peopleâmaybe even youâhave gone through.

I don't blame my parents for not protecting me or my brothers for, well, being brothers. But for some reason, comments that might have rolled off other kids penetrated my spirit like needles in a cushion. You know how it feels when every slight stings like a slap, every joke belies a secret truth, every criticism is a condemnation. And any mistake I made, however minor, only served to support my sneaking suspicion:

I am worthless

.

In response, I shut down. I activated a defense mechanism that I used for many, many years to safeguard the vulnerable parts of myself from outside scrutiny. And part of that defense was my weight.

As I grew older and heavier, my weight became a way of hiding. It gave me an excuse to retreat from tryouts for school plays, from band and choir and sports. Not only that, the weight itself became a cloak, like the cloak Harry Potter and his pals throw on when they want to make themselves invisible. That is exactly how I began to feel, how I wanted to feel: invisible.

I continued to pile on the pounds, stuffing myself as covertly as possible to avoid having to deal with my mother's sympathy or my brothers' ridicule (both were equally annoying). I became a master at hiding, sneaking, and stashing food. If there was a can of frosting in the fridge, my finger had been in it. Chocolate syrup? I'd take a swig from the can while no one was looking. Cookie crumbs in my pockets, candy wrappers in my closetâit's a wonder we didn't have a mouse problem. I was like one of those cartoonish portrayals of an alcoholic who has bottles stashed everywhereâin the toilet tank, under the piano lid, inside a hollowed-out book.