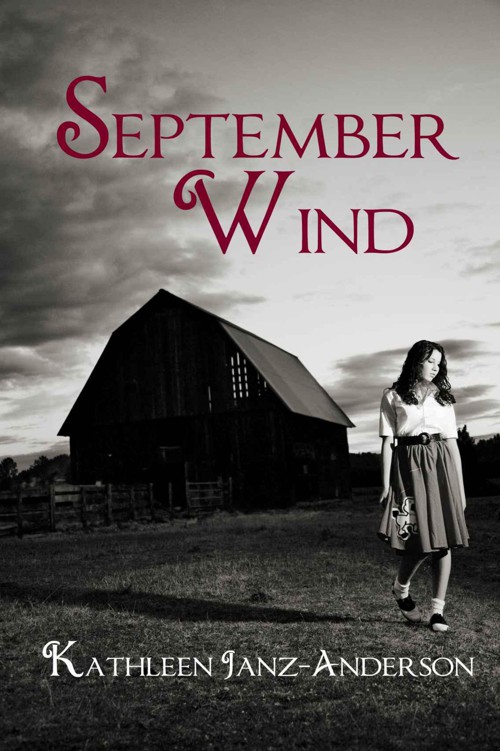

September Wind

Authors: Kathleen Janz-Anderson

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

Cover Art:

Photo: Bruce Berg – BruceBerg.com

Model: Aubree Jones

Select-O-Grafix, LLC. www.selectografix.com

Publisher’s Note:

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and events are the work of the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance to real persons, places, or events is coincidental.

Solstice Publishing - www.solsticepublishing.com

Copyright 2013 Kathleen Janz-Anderson

DEDICATION

In loving memory of

Sharon A Engstrom

August 6, 1974 – July 15, 2005

P

ROLOGUE

Rachael & Emily

1940, Illinois

September wind carried the scent of wheat through the upstairs window where Rachael lay across her bed, angry and in tears.

Six months ago, she leaped from her bed each morning with so much joy, she would sing out the window in high octaves and playful yodels greeting anyone within earshot. Now as the long hot summer turned to fall, and with the bustle of harvest ending, her dreams lay by the side like dying leaves crumbling beneath the feet of ruin. There was nothing to keep her there any longer except for Timothy, her freckle-faced, bushy-haired, stubborn-since-birth brother who sat in a chair at the bottom of the stairs whittling on a pipe.

She blinked away tears and fixed her eyes on the door. “You’re a rotten traitor. And I hate you for it.” She pulled herself out of bed, lumbered across the room, and yanked the door open. “The bus leaves at two, and I’m goin’ no matter what you say.”

Timothy dug his knife into the wood, rolling his eyes.

“I need to use the john.”

“Liar. You went no more’n fifteen minutes ago.”

She blew a wisp of blonde hair from her face, stooped for her suitcase and hobbled down the stairs. “I’ll be eighteen soon, Timothy, and you’ve got no right holding me like this.

He watched her, calmly setting his whittling aside, waiting for her to pass. Then he flew out of his chair, grabbed the suitcase, and marched her back up into her room. “You don’t know what you‘re doing, Sis,” he said, tossing her luggage in behind her. He poked his head in the doorway. “Why don’t you give up? Lay low for a while.” “I’ll never give up. Never!” She reached into a pot of acorns, meant for planting a garden of oak trees, and hurled a handful at him.

He covered his head, taking the steps two at a time, ducking as another acorn whizzed past. It bounced off the far wall barely missing an empty tin can sitting up against the baseboard. He looked up with a miserable sigh, then dropped to his chair and picked up his whittling.

She swung an arm back as if to launch another assault. “You’re gonna be sorry, you...”

He reached for one of the nuts lying on the floor, and she popped her head back in, slamming the door for the umpteenth time that morning. This time the windows shook.

She began to pace, every now and then stopping to shout at her brother, picking up a shoe or anything else handy to throw at the door.

Timothy listened in silence to her hopeless bursts of anger, while winds from the north came in whispers of warning. Finally, out of breath and weary, she took to her bed.

By mid-afternoon, the peaceful milieu of that fall breeze developed into gusts of wind heaving about branches, an army of angry arms that spun leaves to the ground where they would wilt and die as if they had never been.

All of a sudden, the winds dropped and silence filled the air like those uncertain moments after a lightning strike. Timothy’s footsteps came up the stairs and Rachael opened her eyes struggling to sit up. He knocked, opened the door and slid a plate into the room.

“Brought you a sandwich.”

“I’m not hungry,” she moaned, swinging her legs to the floor.

“Suit yourself.” He closed the door and clomped down the stairs.

She pulled on a pair of shoes, then went to the rear window, and looked down to where a ladder had been set up for repairs. It was gone. Turning to the window across the room, she was halfway there when a swift kick to the ribcage took her breath. She stopped in front of the mirror, opened her blouse, and moved a hand over her swollen belly. As she gazed upon her reflection, at eyes filled with pain, a brow lined with worry, and lips that hadn’t smiled for months, she knew if she didn’t leave then, she never would. Shadows from an oak tree with branches nearly bursting through the front window caught the corner of her eye.

She glanced over, then buttoned her blouse and slipped on a sweater. Then she knelt beside her suitcase, unhooked the clasps, and laid it open. Her fingers trembled as she took out just enough items to fill her pockets. Reaching for a sapphire birthstone ring, now too small for her swollen finger, she tucked it inside her bra then pulled herself off the floor and went to the window. Hoisting it open, she held on with both hands, sat on the sill, and heaved a leg outside.

Looking back into her room, she felt nothing but the overwhelming grief that waited if she stayed. The tree, which had been a playground of happier days, was her only way out. She had climbed it so many times even a blindfold couldn’t stop her now. She ducked her head outside, waited for a burst of wind to pass, and then maneuvered her way onto a limb and began to slowly make her way down.

Her descent was almost graceful until the winds picked up again. She looked down through the leaves, and then quickly up to the curtains flapping out the window, realizing it was too late. The moans came first and then powerful gusts of wind hit, one after the other. Leaves ripped from the vines, twigs snapped and then a crack and a jolt beneath her feet turned her blood cold. Her fingernails sliced into her palms as she gripped with all of her might, but it was no use. Her hands slipped from the branch, slowly until they were free, and then she dropped to the ground with a thud. The tempest stilled as she lay. From the quiet, a gust of wind came over the trees, swooped down with a guffaw of laughter and zipped off around the corner with a whimper.

Footsteps approached across gravel, stepping to the wooden sidewalk, across the grass, to the dirt mound where she lay. Rachael opened her eyes and saw Cousin Claude standing above her. She cringed, although for once, it seemed he might have come for the good from his small dwelling set in a grove of trees beyond the barn.

She raised a hand for help, but all at once, a wrenching pain squeezed her insides. She clutched her belly…and then blackness….

Timothy stuck his head of the door. Two puppies scrambled between his legs and down the steps to her rescue. He hopped off the porch and went to look around the corner. “What in the name of…?”

“I think we’re about to witness a birth right here in the front yard,” Claude said.

Timothy froze to the spot as the pickup carrying his parents Rupert and Martha and his brother Steven pulled into the yard.

Steven slammed on the brakes.

They leaped from the vehicle; Rupert before the wheels stopped turning and Steven not far behind, hollering to his brother. As he raced over, “Don’t just stand there gawking, Timothy, get a doctor!”

Steve dropped to his knees beside Rachel and when he saw she was unconscious, he glared up at Claude. “What in the hell happened?”

Claude leaned against the house, lit a cigarette, and tossed the match aside. “Don’t look at me. I didn’t tell her to climb out the damn window.”

Rupert scooped up Rachael in his burly arms and carried her into the house, her mother weeping at his heels. When they got inside, she nodded towards the stairway.

“Up there where she’ll be…where she’ll…oh, Rupert, you know you’ve gone too far this time,” she wailed. “I’m afraid you’ve sewn your last.”

“How was I to know she’d do something like this?” He bowed to gaze at his daughter. “Oh, Rachael, Rachael. What’ve I done? What’ve I done?”

****

Daylight faded as Rachael’s pains grew stronger. When Doctor Grant arrived with Rupert’s sister Francine, the men escaped to the basement with a bottle of whiskey. Francine gathered supplies, keeping pots of water warming on the stove.

Throughout the night, the two Norwegian Elkhounds lay on the porch with their heads resting on their paws. Now and then, they moved their eyes nervously toward her curtain-drawn window as if they were aware of the drama that was taking place inside.

Sometime in the wee hours of the morning, cries of anguish sent hair-raising chills through the house and out into the night. Doctor Grant’s voice rang through the painful fog. “Push, Rachael, push! You’re almost there. That’s it, you’ve done it, you’ve done it.”

There was a snapping sound as the doctor slapped the baby's bottom. The room became still. Then as if in protest, the baby's wails broke the silence. “It’s a girl, everyone. It’s a girl!”

Francine came with warm water and towels, helping attend to mother and baby. Finally, when the doctor could do no more, he nodded to Martha.

Rachael opened her eyes as her mother placed the bundle in her arms, her hands trembling as she pulled back the tiny blanket. Her fingers slid across the baby’s cheek. “Oh Emily, my beautiful little girl, I love you.” She kissed her forehead then looked up at her mother.

“

Ma,” she said, as her mother sat beside her. “Please, Ma. Don’t... Don't cry when I’m gone.”

“

No, honey. No, don’t say that, don’t….”

“

Ma, please... please. Just tell me that you’ll keep her safe.”

Tears poured down Martha’s cheeks as she looked down at the tiny bundle. “I will. I will, but…” She sighed and reached for Rachael’s hand. “Yes, of course. I’ll keep her safe.”

“

And Ma? Tell Timothy I’m sorry.”

“

Whatever for….?”

“

Ma.”

A sob shook Martha’s shoulders. She sat up then, straining to hold it back. “Yes, Honey, yes. I-I’ll tell him.”

Rachael smiled and closed her eyes. Her face filled with peace as she surrendered her mind and soul to the light that waited for her.

Martha gently brushed back her daughter’s hair, kissed her forehead, and then lifted Emily from her arms and carried her to a corner rocking chair. Tears streamed down her face as she rocked and sang to the newborn until exhaustion finally brought her sleep.

Dawn brought a violent gust of wind that sent Martha to the window with the orphaned child cradled against her bosom. She pulled the curtain aside and watched a shadow move across the yard and settle over the barn. The building, already old and weathered with the brush of winds, looked eerie under darkening skies. The

front door squeaked on its hinges, and on top, a rusty weather vane spun out of control.

When the eastern skies lit up with a flash and a distant rumble, Martha dropped the curtain and pulled Emily closer. “The storm’s headed our way, little one. I can feel it in my bones.”