Sergeant Gander (9 page)

“C” Company found themselves being pushed back, down Lye Mun Road into the Tai Tam Gap, and later that day into the Stanley area. Gander had continued to challenge the Japanese invaders, who were relentless in their pursuit of the Canadians. When some Japanese soldiers advanced towards a small group of wounded Canadians, Gander charged at them, barking and growling. The Japanese soldiers changed direction and the wounded Canadians avoided being captured or killed. No one is sure why Gander was able to successfully deter the Japanese, but it is unlikely that any Japanese soldier had ever seen a Newfoundland dog before. Gander was truly an incredible sight, standing over six feet tall on his hind legs. An encounter with Gander was probably quite terrifying for the invading troops. Fred Kelly remembers the Chinese civilians' timid reaction to Gander, stating plainly, “I don't think they [had] ever seen a dog that big.”

15

The battle continued to rage through the early hours of December 19, as the Canadians struggled to cover their withdrawal south through the hills of Hong Kong Island. Bullets and explosions screamed through the air. The men of “C” Company fought hard, inflicting (according to a Japanese officer who was interviewed after the war) “sixty-five percent losses on them.”

16

The Japanese would lob hand grenades up the hills towards the Canadians, who would try to take cover, or if they were quick, would grab the grenades and lob them back down the hill at the Japanese. As the Canadians struggled to hold their positions, a group of seven wounded Canadians lay along the roadside, pinned down by enemy fire. Suddenly, a Japanese grenade appeared, lofting through the air and coming to rest near the Canadian men.

Hissing and smoking, this grenade spelled death for these Royal Rifles. Staring in horror at the deadly object, the Canadians were distracted when a sudden flash of black streaked past them. Their mascot Gander shot forward, grabbed the grenade in his mouth, and took off running. As Lieutenant Bill Bradley recalls:

I saw a small group of Japanese soldiers running from something

on the road where Captain Gavey and his men were lying badly

wounded. One of the men told me later that the soldiers were

running from a big dog. They told how Gander had charged

out and gathered the grenade in his mouth before it reached the

Captain's group.

17

The grenade exploded in Gander's mouth. Rifleman Reginald Law remembers:

The last time I saw Gander alive he was running down the road

towards the Japanese soldiers. Then there was an overly heavy

amount of fire and I heard several grenades exploding close to our

group. When the firing eased up I saw Gander lying dead on the

road. He was in the open ground, between us and the Japanese,

so no one could get close. With the enemy still advancing we had

no choice but to leave him.

18

Gander had given his life to save seven wounded Canadian soldiers. Fred Kelly was devastated to learn of Gander's death. Although the dog was adored by all of the men of the Royal Rifles, Kelly was the one with the closest bond to Gander.

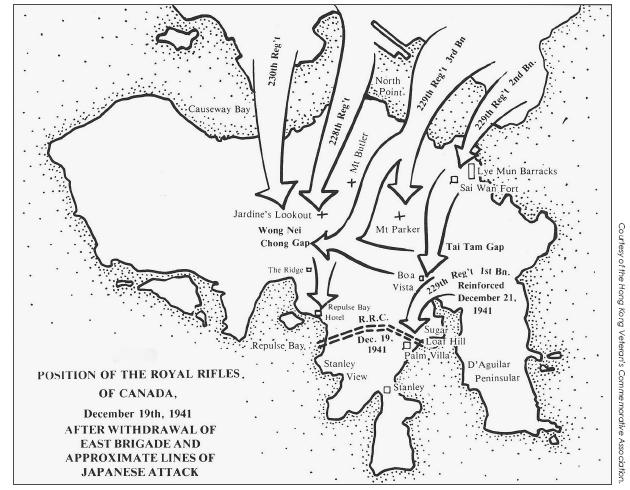

The positions of the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Japanese lines of attack, December 19, 1941.

Kelly remembers, “I seen him the next morning ⦠he was dead the next morning ⦠but I didn't go near. I was so distraught ⦠I didn't go look at him, I just seen him in the distance.”

19

Sergeant Gander's death is recorded in the list of “C” Force Soldiers Killed or Missing in Action or Died of Wounds as occurring December 19, 1941. To be more accurate, his heroic act most likely took place sometime during the night of December 18/19. The confusion of battle makes it difficult to pinpoint events exactly, but it is possible to gauge with some accuracy when his fateful charge took place. It is documented that Lieutenant Bradley, who witnessed the Japanese running down the road away from the injured Captain Gavey (and his men), was ordered, along with Captain Gavey, to attack Sai Wan Fort at 2235 hours on the 18th. Obviously Gavey was not injured at this point, but did sustain his injuries while the Canadians were attempting to disengage after the abortive attack on the Fort, a walled fortification located on Sai Wan Hill. Tony Banham's book,

Not

the Slightest Chance

, records the death of Rifleman Gordon Irvine, on December 18, and indicates that Irvine was “killed by the same shell that injured Captain Gavey.”

20

This is most likely the injury that left Gavey and his men lying wounded by the side of the road, sometime after 2235 hours on the 18th.

Fred Kelly, who was busy fighting off the Japanese invaders, has indicated that, “The night they landed I took it for granted that Gander was in the pillbox ⦠when they started mortaring and shelling I think what actually happened was he got scared and run out of the pillbox ⦠probably that's when he met the Japanese.”

21

Kelly confirms that Gander was killed the first night the Japanese landed on Hong Kong and that he didn't actually see what happened to Gander because “it was pitch dark.”

22

Kelly also indicates that he saw Gander's body the next morning. Clearly, sometime during the late hours of December 18 or the early hours of December 19, Gander's war came to an end.

Despite the loss of their mascot the Royal Rifles had to continue the fight. It was a lost cause, however. The Japanese continued to press their advance, and although several brave counter attacks were made by the British and Canadians across the Island, they were outnumbered and outgunned. A soldier from the Royal Rifles recalls:

Christmas night, we were up on a ridge in front of Fort Stanley

waiting for an attack. There was no attack because there was a

truce at the time, pending negotiations between the governor of

the Island and the invading forces. The most frightening thing

POW information

There are countless eyewitness reports of the brutality towards civilians and captured

soldiers that was demonstrated by the Japanese. Many of these atrocities were addressed

at the Hong Kong War Crimes court in 1946. The Japanese's brutal treatment of

their prisoners stemmed largely from the fact that they never ratified the 1929 Geneva

Convention,

27

which outlined what was deemed as acceptable conduct regarding the

treatment of prisoners of war. Moreover, Japanese soldiers were encouraged to perceive

being taken prisoner as shameful, and their soldiers' handbook stated, “Do not fall

captive, even if the alternative is death ⦠Bear in mind the fact that to be captured

not only means disgracing the army, but your parents and family will never be able

to hold up their heads again. Always save the last round for yourself.”

28

With this type of mindset it's hardly surprising that the Canadian prisoners of war

were treated so badly. After their surrender the Royal Rifles were transported across

Hong Kong Island to the North Point Camp. The Winnipeg Grenadiers were taken

back to the mainland and housed at Sham Shui Po until January 23, 1942, when they

and the Royal Navy prisoners were taken back to the Island to join the Royal Rifles

at the North Point Camp. Three months later the Royal Navy prisoners were moved

again and North Point became an all-Canadian camp.

29

In September of 1942, the

Canadians were moved back to Sham Shui Po on the mainland, which had been largely

vacated due to the transfer of the British prisoners housed there to work camps in Japan.

Throughout 1943 and 1944 the Canadians were also transferred to work camps in

Japan, where they were forced to work in coal and iron mines, and in the dockyards.

No matter where the prisoners were located, their living conditions and treatment

by the Japanese were brutal. Living quarters were always crowded and poor sanitary

conditions prevailed. Food was inadequate at best, and there was an acute lack of

medical supplies. Diseases such as beri beri, pellagra, dysentery, and diphtheria were

prevalent in the camps. The Japanese guards were often ruthless in their treatment of

the prisoners and “slaps, blows from fists and rifle butts, or prods from bayonets for the

slightest transgression” were not uncommon.

30

was looking out and seeing the glow of thousands of cigarettes.

The Japanese down below had been told we'd surrendered, so

they all sat down and started smoking cigarettes. Then we realized

how close they were, and how many they were, and how impotent

we were.

23

On Christmas Day the Allied forces on Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese. At the time of surrender the East Brigade had been pushed down into the tip of the Stanley peninsula, and the West Brigade held a line that ran roughly from Bowrington in the north to Aberdeen in the south â less than a quarter of the Island's territory was held between them.

24

The Hong Kong garrison reported over 2,000 men killed or missing, with twice that number being wounded. The Canadians incurred 290 fatalities, with nearly 500 wounded.

25

Those who had not been killed in the battle were

Commander Peter MacRitchie of the

Prince Robert

meeting with liberâated Canadian POWs at Sham Shui Po Camp, September 1945.

destined to spend the rest of the war living in horrific conditions in Japanese prisoner of war camps. Those who survived the camps returned home to Canada when the Japanese surrendered in 1945, and they never forgot their heroic canine comrade who had made the ultimate sacrifice during the Battle of Hong Kong. Sergeant George MacDonell states, emphatically, “No two-legged soldier did his duty any better and none died more heroically than Sergeant Gander.”

26

The prisoners were liberated in August 1945, when the Japanese surrendered to the Allied forces. At the end of August the transport ships that would carry the surviving Canadians back home to Canada arrived. Ironically, one of these ships was the

Prince Robert

, which had transported many of the Royal Rifles to Hong Kong back in 1941. The number of Canadians who returned home was markedly fewer than had made the journey to Hong Kong. In addition to all of the men lost in the battle, 128 died in the Hong Kong POW camps, 136 died in work camps in Japan, and four men were executed after an escape attempt. In total, 557 of the original Canadian contingent did not return home.

29

The Canadian soldiers who returned to Canada formed the Hong Kong Veterans' Association (HKVA) in 1948, in response to a wide variety of complaints that the veterans had experienced since returning home. Many had returned from Hong Kong with a range of medical ailments resulting from their captivity, and they felt that existing government benefits and compensation were inadequate to address their needs. They also wanted compensation for their years of forced labour in Japan's work camps. In 1965, they ratified their association's constitution, which listed the aims of the HKVA as:

To assist all members in times of need,

To maintain and improve social welfare and friendship among

members and their dependents”

To promote legislation for the physical well being of all members

of “C” force or Allied personnel who were imprisoned by Japan

1941â1945.

1

As a result of the HKVA's determined advocacy, significant gains were made in terms of compensating the veterans and their families, for their service in Hong Kong.

As health concerns and advancing age began to impact the HKVA's ability to fulfill their association's agenda, a proposal was made in 1993 to create a new association, made up of the sons and daughters of “C” Force veterans. In 1995, the new association was given the name the Hong Kong Veterans' Commemorative Association (HKVCA). Their mission is describd as “to educate all Canadians on the role of Canada's soldiers in the Battle of Hong Kong and on the effects of the internment of the battle's survivors on both the soldiers and their families. We