Read Seven Elements That Have Changed the World Online

Authors: John Browne

Seven Elements That Have Changed the World (21 page)

He had little initial luck and was fast running out of money when, in 1960, he struck a last-ditch deal with BP. He agreed that BP could drill in Block 65 for a 50:50 split of any oil found. The gamble paid off; in November 1961, BP struck the huge Sarir oilfield, estimated to hold between eight and ten billion barrels, at least half of which was thought to be recoverable.

49

Even with the low oil prices of the 1960s, Hunt’s half-share would be worth an impressive $4 billion which, along with the fortune inherited from his

father, made him the richest man in the world. But the fortunes of both BP and Bunker Hunt were soon to change when, in 1969, a coup brought Colonel Muammar Qaddafi to power. British troops had taken a role as a guardian in the Persian Gulf since 1835 but in December 1971 they were about to withdraw. The day before their departure, Iran inserted itself in the power vacuum by taking control of three small strategic islands. The British did not resist the occupation, provoking a backlash from the rest of the Arab world. BP was at the time majority owned by the British government. So, as an act of retribution against Britain, Qaddafi nationalised BP’s Libyan oil operations.

50

Hunt was still able to produce his share of the Sarir oilfield, some 200,000 barrels a day, but the next year Qaddafi ordered all the oil companies to give Libya a 51 per cent share. Unlike many other companies, Hunt refused. In April 1973, his Libyan operations were nationalised to give, as Qaddafi expressed it, ‘a slap on America’s cool, arrogant face.’

51

Bunker Hunt had become the richest man in the world and then gambled and lost almost everything. It would take a daring business mind to gamble again, but Hunt did just that. Oil no longer seemed a safe investment and so he invested in real estate and horses, which were his hobby.

52

He also turned his attention to silver.

In the 1970s, silver seemed an increasingly safe store of value. High inflation was eroding the value of money and precious metals looked like a good investment. Silver, which was selling at a low of $1.50 an ounce, seemed more of a bargain than gold. Hunt’s view was that ‘just about anything you buy, rather than paper, is better. You’re bound to come ahead in the long pull. If you don’t like gold, use silver, or diamonds, or copper, but something. Any damn fool can run a printing press.’

53

Bunker Hunt’s brother, William Herbert Hunt, was also interested in investing in silver.

54

He had swallowed the assertions in

Silver Profits in the Seventies

by Jerome Smith which declared that ‘within our lifetime, and perhaps within the decade, silver could become more valuable than gold’.

55

Herbert Hunt explained his logic for investing: ‘My analysis of the recent economic history of the United States has led me to believe that the wisest investment is one which is protected from inflation. In my opinion natural resources meet this criterion, and, to that end, I have invested in oil, gas, coal, and precious metals, including silver.’

56

In the early 1970s, the ratio of the value

of gold to silver was around 20:1. Bunker believed that this ratio would eventually return to its historical level of around 10:1, which, according to his logic, meant that, even if gold remained at its then prevailing price, silver would have to double in value.

The Hunts began buying millions and millions of ounces of silver. By early 1974 they had contracts totalling 55 million ounces, around 8 per cent of the world’s supply. Unusually, they were taking physical delivery of their contracts. They were looking for more than short-term profits from speculation; they wanted to create a permanent and literal store of value. But by taking ownership of silver, they began to reduce its physical supply and drive its price higher and higher. Worried about the US government interfering, as they had done with gold in the 1930s, the Hunts decided to move a good portion of their silver to vaults in Europe.

57

At a 2,500-acre ranch to the east of Dallas they recruited a dozen cowboys by holding a shooting match to find out who were the best marksmen. The winners got to ride with guns on three unmarked 707s, protecting the Hunts’ silver hoard on a flight to Europe. Arriving at New York and Chicago in the middle of the night, they loaded 40 million ounces of silver from armoured trucks on to the aeroplanes. The cowboys climbed aboard and then flew to Zurich, where the bullion was delivered to six secret storage locations.

But storing silver was very costly; to stop their wealth being eroded, the Hunts needed prices to increase, not just hold steady. Fortunately a combination of the Hunts’ bullish behaviour on silver, new big buyers in the market and the general trend in commodity prices during the high inflation of the 1970s led to just that. Between 1970 and 1973 the price of silver doubled, rising to $3 an ounce, and by autumn 1979 it had reached $8 an ounce. Then suddenly in September it leapt to over $16 an ounce. As a result of their buying, the Hunts faced investigation by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). The CFTC was growing worried that a silver squeeze (in which insufficient bullion is available to meet future contracts) could be on the horizon, and so they asked the Hunts to sell some of their silver. The Hunts abhorred federal interference and, characteristically, declined.

Instead they kept on buying. By the end of that year, the Hunts controlled

90 million ounces of bullion in the US, with another 40 million hidden in Europe and another 90 million through futures contracts. On the last day of 1979 the price had reached $34.45 an ounce. By the beginning of 1980, the CFTC became increasingly worried and determined that the Hunts were ‘too large relative to the size of the US and world silver markets’.

58

Backed by the CTFC, the trading market announced new limits restricting traders to no more than 10 million ounces’ worth of future contracts. But still the price kept rising and the Hunts kept buying silver outright. On 17 January the price reached a new high of $50 an ounce. At this point, the Hunts had silver holdings worth nearly $4.5 billion and their unrealised profit on this was around $3.5 billion.

59

The authorities reacted four days later by closing down the silver futures market, with disastrous consequences for the Hunts.

60

The price of silver plummeted to $34 an ounce, levelling out in this region for the rest of the month. The price was partly kept down by people selling scrap silver, digging out old silver dinner place settings to melt into bullion. ‘Why would anyone want to sell silver to get dollars?’ asked Bunker. ‘I guess they got tired of polishing it.’

61

The Hunts kept taking delivery of their contracts, now holding stock of over 155 million ounces. They had faith in the long-term price of silver and tried to turn the price decline around. By 14 March the price of silver had fallen to $21 an ounce. On 25 March, the Hunts realised they no longer had the resources to keep making margin calls. Bunker sent a message to Herbert: ‘Shut it down.’ Their brokerage firm called asking for a further payment of $135 million to maintain the futures contracts. Herbert told them that they could not pay and that they would have to begin selling; as they did, panic took over the market. On Thursday 27 March, ‘Silver Thursday’, the silver market collapsed, falling to $10.80 an ounce. The Dow Jones dropped twenty-five points to its lowest level in five years. To pay their debts, the Hunts had to keep selling their silver, depressing the price further. And they also had to pledge their personal possessions, including ‘thousands of ancient coins from the 3rd century

BC,

sixteenth-century antiques, Greek and Roman statuettes of bronze and silver … a Rolex watch, and a Mercedes-Benz automobile’.

62

The Hunts had made billions in profit on their investment, and now had lost it all. Bunker Hunt was twice the world’s richest private individual

(once by oil, once by silver) and twice had lost his fortune.

63

He still believed the price of silver would rise again, predicting it would one day reach $125 an ounce. But silver had probably had its last gasp. The Hunts’ actions in the silver market put them in the media spotlight, where they were portrayed as greedy and conniving. They were hounded by the press, but as Bunker Hunt told a friend: ‘At least I know they’re using a little bit of silver every time they take my picture.’

64

Since the first Kodak came on to the market in 1888, cameras and silver halide film had spread throughout the world. In 1980 silver images were more prolific than ever before. However, only thirty years later, this would all change. The 2012 Oscar’s ceremony took place, unusually, without a sponsor. Kodak, whose name had been associated with the awards since 2000, had gone bankrupt. The pioneers of affordable cameras and film had failed to keep up with the shift to digital photography. On the red carpet, the press pack did not even use the tiniest bit of silver each time they took a photograph. In 2012, the silicon CCD chip was the medium of choice for recording images. Silver changed so much of our world, not only as a store of value but also as the essential ingredient in a technology allowing us to capture images of history. Silver-halide photography had a remarkable 150-year impact on the history of human invention, but that had now largely come to an end. While our reverence for gold, ‘the sweat of the Sun’, remains the same today as it did three millennia ago, we shed a tear for the ‘tears of the Moon’ and its gradual demise as an element which changed the world.

65

The bomb

28 O

CTOBER 2011: I

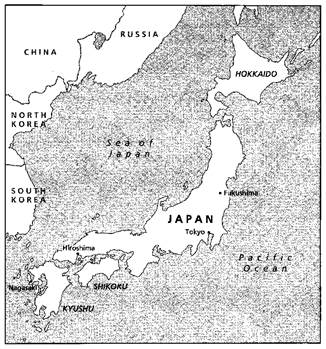

am standing outside the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, Japan. A plaque, 100 metres to the north-east of the museum, marks the hypocentre of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima at 8.15 a.m., 6 August 1945.

1

Seventy thousand people died as a direct result of the explosion and many more died later from their burns and radiation sickness. The entire city was obliterated.

2

The Peace Park’s central boulevard points me towards the Atomic Bomb Dome, next door to the ‘T’-shaped Aioi Bridge which served as the aiming point for the crew that dropped the bomb. The Dome was one of the few buildings left standing after the blast and the fires which swept through the city. The hollow, twisted structure has been kept in its bombed state as a lasting reminder of the destructive potential of atomic and nuclear weapons and as a memorial to those who lost their lives. But around the Atomic Bomb Dome and symbolically flat Peace Park, the city has been reborn. By 1955 the population of the city had surpassed the level reached before the bomb was dropped. Skyscrapers now dominate the skyline and the starkly contrasting Dome seems to have become ever smaller through the decades of Japan’s post-war economic miracle.

In front of me is a sea of matching yellow, blue and green hats. Each day hundreds of school children visit the Peace Park. Some laugh and play games while others listen intently to their teachers. The Peace Bell frequently chimes out across the park as small groups take it in turns to swing the wooden ringer. They are all here for one reason: to learn about the tragic events of the day the bomb was dropped and why it must never happen again.

On display inside the museum is a collection of pictures made by Hiroshima survivors.

3

The images were produced decades after the bomb, but memories of that day are clearly still sharp. The individual hurt and terror is magnified as I move from picture to picture. The collection forms a partial documentary of human suffering. Drawn by the hands of survivors and registering what had been burnt in their minds, the images make a greater impact than that of any photograph. Many did not get to tell their story: a burial mound in the park still holds the cremated remains of thousands of unnamed victims.

The simplest images are the most affecting. In the middle of one blank white page sits a coarse black ball, limbs barely discernible. The flash of

the atomic bomb was so quick that there was no time for any cooling to take place; asphalt boiled and skin simply burnt. The witness to this event continues: ‘The whole body was so deeply charred that the gender was unrecognizable – yet the person was weakly writhing. I had to avert my eyes from the unbearable sight, but it entrenched itself in my memory for the rest of my life.’

4

The Hiroshima survivors cannot forget; we must ensure that we do not forget.

At a dinner several weeks earlier, I had heard George Shultz, the former US Secretary of State, say that the abolition of nuclear weapons was his essential motivation.

5

At the time, I had not fully understood his drive, but as I stood in the Peace Park reflecting on the events of sixty-six years ago, it became clear to me. I felt the same when I had visited the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, with my mother. Almost all her family died in the Second World War. She herself survived Auschwitz. Humans cannot be treated like vermin to be eradicated. The Holocaust was a planned programme of inhuman events for an evil reason; the Hiroshima bomb was a single dreadful event to stop a continuing inhuman war. I cried, much as I did when I saw my mother put a candle on the Auschwitz memorial. And I remembered my mother telling me off as we left the museum with a question and a statement. ‘Why are you crying? It is just a museum. There is no noise and it does not smell.’ And in that way she reminded me that there is no room for sentimentality, only clear-eyed realism.