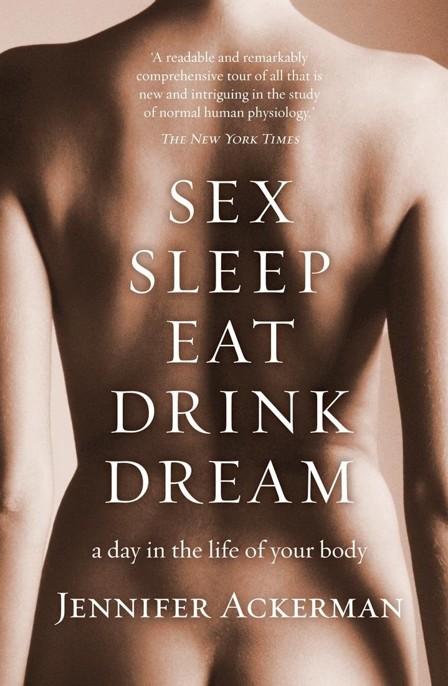

Sex Sleep Eat Drink Dream

Read Sex Sleep Eat Drink Dream Online

Authors: Jennifer Ackerman

Sex Sleep Eat Drink Dream

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF YOUR BODY

Jennifer Ackerman

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston • New York

2007

Copyright © 2007 by Jennifer Ackerman

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections

from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ackerman, Jennifer.

Sex sleep eat drink dream : a day in the life of your body/

Jennifer Ackerman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN

-13: 978-0-618-18758-4

ISBN

-10: 0-618-18758-8

1. Body, Human—Popular works. 2. Human

physiology—Popular works. I. Title.

QP

38.

A

155 2007

612—dc22 2007008516

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

Printed in the United States of America

MP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book presents the research and ideas of its author. It is not intended to be a substitute for consultation with a medical or other professional. The author and publisher disclaim responsibility for any adverse effects resulting directly or indirectly from information contained in this book.

To my father,

William Gorham,

WITH LOVE

Contents

Prologue xi

Morning

1.

AROUSAL

• 3

2.

MAKING SENSE

• 16

3.

WIT

• 27

Midday

4.

THE TEETH OF NOON

• 43

5.

POST-LUNCH

• 54

Afternoon

6.

THE DOLDRUMS

• 73

7.

STRUNG OUT

• 84

8.

IN MOTION

• 98

Evening

9.

PARTY FACE

• 119

Night

10.

BEWITCHED

• 135

11.

NIGHT AIRS

• 145

12.

SLEEP

• 157

13.

HOUR OF THE WOLF

• 175

Acknowledgments 191

Notes 195

Index 237

I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which

I am bound ... Talk of mysteries!

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

Prologue

YOU ARE YOUR BODY

. It holds you in and holds you up. It constrains you and controls you, delights and disgusts you. And yet its activities are mostly a mystery. Let's face it: We're all body-conscious to one degree or another, acutely aware of our physical façades—the symmetry and wrinkle of face, the curve of torso, girth of thigh, roll of belly, flare of feet. But how many of us have a handle on the drama unfolding inside? As Saint Augustine said, we go forth to wonder at the heights of mountains and the courses of the stars, yet pass by the miracle of our own inner lives without wondering. In health, the body often operates so smoothly that we can almost forget it exists. Most often it's some failure or perturbation that captures the attention. In fact, many of us spend our time trying

not

to be aware of what's occurring within. No news is good news.

Not so. This came home to me some time ago when I succumbed to a virulent flu after a stressful run of life. The flu sucked the juice out of me for weeks and robbed me of all the facets of physical existence I relish: the satisfactions of work and exercise, the sweet smell of my children and other sensual pleasures, appetite and eating, restful sleep. When I emerged from my illness, I felt not only the relief and joy of having my body back, but a sudden sharp desire to learn more about it. What was the nature of those pleasures my healthy body so enjoys? And the problems that occasionally plague it? I realized I didn't have a clue what went on inside me, in sickness or in health. I had no idea, for example, what underlies digestion and its precursor, hunger—that mysterious loop that translates the absence of nutrients into the craving for comfort food—or, for that matter, its antithesis, nausea. I hadn't the foggiest idea what a virus did to my body, or alcohol to my brain, or cumulative stress to my energy and health. I knew my body did some things more effectively in the morning, others in the afternoon or evening, but didn't have an inkling why.

Though that bout of flu was hardly a near-death experience, it did remind me that my whole existence was going to come and go in this same ark of skin and blood and bones; the "go" part, of course, loomed closer every day. Even the long-lived among us are alive for only about 700,000 hours. My body would exist only once; I would never have another one. Wouldn't it be a good idea to get to know it a little?

When I was in first grade, I had a fine grasp of my inner life. I knew that my heart beat somewhere inside my left chest, near where I put my hand to pledge allegiance. I knew that when I brushed my hair, I was stroking dead cells, a grotesquery I gleefully shared with friends at every opportunity. I knew that what my stomach took in as a snack—say, a whole box of raisins—might have later consequences. I knew I would get cranky if I didn't have a nap. Beyond that, I didn't give it much thought. This went on, more or less, for thirty years. Then came that flu that struck like lightning on the road to Damascus.

To remedy my ignorance, my first thought was medical school. I imagined poring through

Gray's Anatomy,

committing to memory nerve and bone, perusing the

Lancet

and the

New England Journal of Medicine

for case studies describing mysterious clinical syndromes: "A lo-year-old girl with recurrent bouts of abdominal pain," or "A 22-year-old man with chills and fever after a stay in South America." Medicine had the appeal of detective work: observing closely, analyzing, diagnosing, offering treatment. But starting a medical education from scratch at the age of thirty-five would rule out normal life well through my childbearing years.

Also, I did know one thing about my body. It lacks the constitutional prerequisite for the kind of schedule demanded of doctors: It needs sleep. The night before committing myself to a two-year post-baccalaureate premedical program, I dreamed of diving off a bridge and landing headfirst in a slough of mud. In the morning, I canceled my medical school plans.

It was another decade before I got around to tackling the topic as a writer. Over the next several years, I hunted everywhere I could for the latest engaging news about the body. I read dozens of books and hundreds of journals. I prowled the laboratories of scientists and attended their conferences, meetings, and lectures. I observed significant events in my own body and subjected it to numerous tests and experiments.

I discovered that it was a good thing I waited as long as I did. Much of what we know about the body we've learned only recently from an explosion of new discoveries. In the past five or ten years, science has made a great leap forward in grasping the underpinnings of everything from hunger and fatigue to exercise, perception, sex, sleep, even humor. We know things about the body that were scarcely imaginable a decade ago—exactly which brain regions are active as you read this sentence, for instance, or what cumulative stress does to your waistline, or how exercise can help you learn. This fresh news suggests answers to questions that once seemed beyond the reach of science: Why do you succumb to a cold and your partner does not, even though you were both exposed to the same sick child? Is there a biological basis for spousal arguments over whether those red pants match that crimson shirt? How is it that your colleague can eat anything she likes and never gain an ounce, while you just look at a doughnut and put on half a pound?

In the past decade, we have learned that the human body is only 1 percent human and 99 percent microbial, at least in terms of cell count. (That you and I don't

look

more germ-like is due to the small size of bacterial cells relative to our own.) We know that just thinking about exercise may increase muscle strength, and that too little sleep can lead to too much weight gain. We have begun to see that "timing is everything"—that if you want your body to go through life at its best, you should pay close attention not just to what you are doing, but when you are doing it.

Some of what we've learned has come from studying cases in which normal bodily functions have failed. As the seventeenth-century English anatomist Thomas Willis said, "Nature is nowhere accustomed more openly to display her secret mysteries than in cases where she shows traces of her workings apart from the beaten path." From appetite gone awry we've glimpsed the chemical essence of hunger. From a failure to recognize faces we've garnered new insights into the miracle of face perception; from one who "lost touch" we've learned about the biology of a caress.

Other scientific breakthroughs have arisen from innovative tools for seeing inside the body. In centuries past, studies have required a bizarre injury to expose the previously concealed innards of an unfortunate patient. The closest thing we had to a real window on the workings of an organ was accidental—a chance hole in the stomach of Alexis St. Martin, for example, which gave an army doctor named William Beaumont an intimate view of the digestive organ at work. This was followed by the first x-ray photographs in the twentieth century, which yielded clear but static images of bones in their misty envelope of flesh. In the past ten or twenty years, new imaging techniques—positron emission tomography

(PET)

scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)—and ways of "listening in" on the activities of cells have allowed detailed looks inside the living, working body. Brain scans have pointed a bright spotlight at what's happening in the brain in real time as we recognize a face, learn a new language, find our way around a Byzantine city, follow a Bach sonata, or get a joke. With tools that allow us to eavesdrop on the cells of the human gut, we've discovered the existence of a "second brain" there, as well as a world of organisms living in its twisted topology of villi and crypts.

So, too, huge strides in genetics have helped us explore in a whole new way the fundamental workings of organs, tissues, and cells. The lion's share of new knowledge on human genes has been gleaned from the study of other organisms: mice, fruit flies, zebra fish. Much to the delight of scientists, the mechanisms that run creatures from fungi to humans often have a common basis. What is true of lowly yeast is also true of you.

Among the fascinating new findings is this: An essential part of our inner life is rhythmic. "Our body is like a clock," wrote the scholar Robert Burton in 1621. It's true. We are not just time-minded but time-bodied, right down to our very core. The human body possesses a whole shop of internal clocks that measure out our lives. These timekeepers tick away in a "master" clock in the brain and in the individual cells throughout our flesh, affecting everything from the time we prefer to wake up in the morning to the accuracy of our afternoon proofreading, our speed during an evening run, even the strength of our handshake at a late-night party. We are usually unaware of the internal rhythms generated by these clocks, sensing them vividly only when we abuse them, during shift work, jet lag, or adjustment to daylight-savings time. Yet they govern the daily fluctuations of a surprising range of bodily tasks, from the operation of individual genes right on up to complex behaviors—how we perform in sports, tolerate alcohol, respond to cognitive challenges. By timing your actions so they're in concert with these rhythms, you can maximize your performance at a meeting or minimize your dental pain. By defying them, you may cause yourself real harm.

This is a book about the new science of your body, the many intricate and intriguing events occurring inside it over a twenty-four-hour day. There is, of course, no typical day. Nor is there a typical body experience. (In using the first person, I am borrowing a tack from Thoreau: "I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew as well.") Physicists may deal in uniformity, in things that are all the same, such as electrons and water molecules. But biologists must cope with staggering diversity. No two animals are alike, even when they're clones. The same is true for two cells and two molecules of DNA. And while recent research suggests that we humans are genetically more alike than we are different, we are nevertheless marked by millions of small but significant distinctions of anatomy, physiology, and behavior. We diverge in our appetites and metabolism and in the way we taste and see. We differ in how we tolerate stress and process alcohol and in our preferences for bedtime and waking time. One man's tonic is another's poison. One woman's stimulus is another's trauma. One body's night is another's dawn.