Read Sexuality, Magic and Perversion Online

Authors: Francis King

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Counter Culture, #20th Century, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

Sexuality, Magic and Perversion (16 page)

“Sir John Froissart, the only writer of the age that treats of this institution, assigns no such origin as the picking up of the Countess of Salisbury’s garter; nor does he adduce the words of the motto of

the Garter as having been spoken by King Edward the Third when encountering the laughter of his court, and assuring them that he would make the proudest eventually wear it as the most illustrious badge. There can be only one conclusion as to the character of the investment which was picked up; and which article of dress makes it clear that the Countess of Salisbury—or the lady, whoever she may be, who has succeeded in becoming so celebrated in the after ages of chivalry—should have rather been at home,

and at rest

, than inattentive to saltatory risks in engaging in a dance at a crowded court. There was no mention of this supposed picking up of a garter for 200 years, nor was there anything referring to such an origin occurring in any of our historians other than Sir John Froissart, until Polydore Virgil took occasion to say something of it in his notices of the origin of the Order. In the original Statutes of the Order (which is a most important point in the inquiry), there is not the least conjecture expressed, nor does the compiler of that tract entitled

Institutio clarissimi Ordinis Militaris a praenobili Subligaculo nuncupata

, to the

Black Book of the Garter

, let fall any passage on which to ground the conclusions about the Garter. Polydore does not mention whose garter it was; this he cautiously declines to do. He says that it was either the Queen’s, or that of the King’s mistress,—meaning Joan, Countess of Salisbury, with whom it was supposed the King was in love, and whom he relieved when she was bravely holding out for him against the Scots, in her Castle of Wark-upon-Tweed; but she was certainly no mistress of the King’s, in the injurious and unworthy sense. It is to be particularly noticed that the Latin words

subliGAR, subligaculum

, mean,

not

a ‘garter’, but ‘breeches, drawers, or trousers’. It was therefore not a garter for the leg, but a cincture for the body, which was thus picked up publicly, and elevated for honour, as such an unexpected illustrious object; one around which the most noble knights were to take enthusiastic oaths of devoted homage. Now, unless there had been some most extraordinary meaning under all this (lying under the apparent, but only apparent, indecency), such an idolising could never have occurred, and the whole occurrence ages ago would have been laughed into oblivion, carrying the sublime honours of the ‘Garter’ with it. Instead of this, the Garter is the highest token of greatness the Sovereign of England can bestow, and it is contended for and accepted with eager pride by Princes. ‘Subligaculum,

breeches, drawers, trousers’

. ‘Subligatus,

cinctured, bound

, etc.,

wearing drawers’

. The origin of the ‘Garter’ is proven in this word not to be a garter at all.

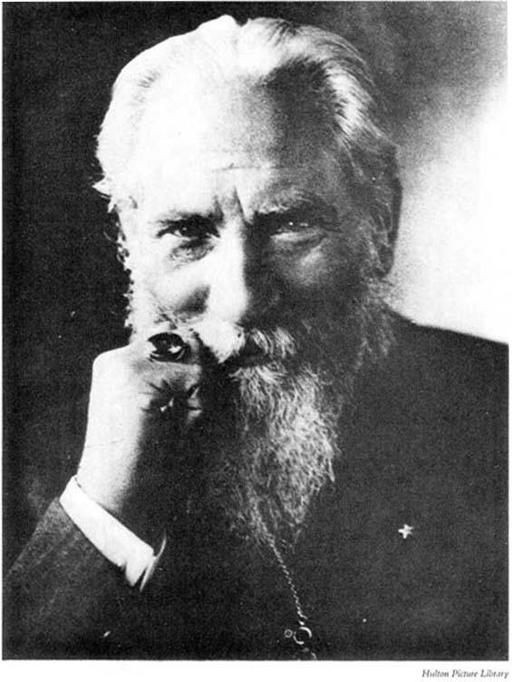

5. Bishop C.W. Leadbeater—see “The Bishop and the Boys”.

6.

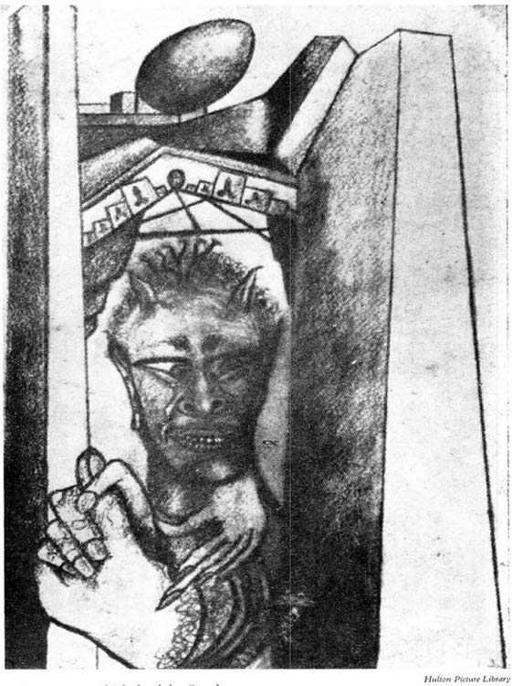

Satan

—a pen and ink sketch by Crowley.

“It is most generally supposed that it was on January 19th 1344, that King Edward instituted his famous Order of the Garter. This period, it will be perceived, was almost within an octave of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary; under whose patronage, and under the guardianship of St. George on earth (St. Michael in Heaven; both these Saints being the same, with earthly and spiritual attributes refluent respectively), King Edward placed his profoundly religious Order. The whole was a revival of the ‘Round Table’ of King Arthur, or the apotheosised female

discus

in certain mythical aspects. To confirm us in our assertion of the feminine origin of the Order of the Garter—which many in their ignorance have questioned we may state that one of the old chroniclers, though somewhat guardedly, as befitted those of whom he spoke, declares that the lady who let fall her garter, or ‘garder’, was the

Queen

, who had suddenly left the courtly assembly in some confusion, and was hastening to her own apartments, followed by the King, who, when the spectators avoided lifting the article, being aware to whom it belonged, raised it himself, and called aloud, not the words of the motto of the Garter, which the historian says that the Queen herself spoke, but an intimation that he would, spite of their laughter, ‘make the proudest of the refusers wear the rejected cincture as the grandest badge that knighthood ever bore.’ Rightly viewed, this little evaded incident—which we desire to restore to its proper place in the knowledge of Englishmen—is the most conclusive proof of King Edward’s nobleness and greatness of heart, and of his chivalrous, gallant delicacy; an instance admirable to all future generations, and worthy of the most enduring applause. The reader finally is referred to our observations in a previous part of our book for evidence in our justification. In the foregoing we give the Rosicrucian view of the origin of the ‘Garter’. It is the centre-point round which have converged the noblest ideas and the most illustrious individuals in the world. It is still the proudest and most solemn badge, and the chiefest English knightly dignity. Strangely enough, too, this whole history of the ‘Garter’ teaches, as its moral, the greatness of the proper independence of shame, and the holiness of its unconsciousness.”

5

My readers may well feel that the logomachy, specious reasoning and incomprehensible hinting displayed in the passage I have reproduced above are clear indications that the works of Jennings are quite unworthy of any serious attention. This was not, however, the opinion of Victorian occultists; Theosophists, mesmerists, spiritualists and esoterically inclined freemasons read Jennings’

Rosicrucians

and received, as they thought, illumination. A pirated version of the book appeared in the United States and a German translation of it was also made. I have no doubt that the last-mentioned work did a great deal to clear the ground for the German sexual Templarism of the early twentieth century.

1

Hamilton is, of course, best remembered as the elderly and cuckolded husband of Emma, Lady Hamilton, the mistress of Nelson.

2

This seems to have been the euphemistic name bestowed by the Church on the holy relic, i.e. the dried and mummified penis of the Saint. F.K.

3

He wrote that “Men, considered collectively, are at all times the same animals, employing the same organs, and endowed with the same faculties: Their passions, prejudices, and conceptions, will of course be formed upon the same internal principles, although directed to various ends, and modified in various ways, by the variety of external circumstances operating upon them!”

4

“Flowers” was, of course, a Victorian euphemism for menstruation.

5

Jennings also suggested that the motto of the Order,

honi soit qui mal y pense

, should read

yoni

(i.e. vagina)

soit qui mal y pense

. For some description of Jennings’ involvement with masonic Rosicrucianism see my

Ritual Magic in England

.

Templarism and Sex Magic

The original Order of the Temple had been founded in 1118 by two French Knights as a military-monastic fraternity with the twin functions of defending the newly established Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem against the infidel and protecting poor pilgrims. At first its brothers were subject to a most rigorous discipline, for they not only took oaths of poverty, chastity and obedience but submitted themselves to the austere Cistercian version of the Rule of St. Benedict. With time, however, the Order became rich, and with wealth came an inevitable relaxation of physical and moral discipline; it is probable that this tendency owed at least something to the Templars’ contacts with the sophisticated civilisations of mediaeval Islam.

As early as 1238 Pope Gregory IX had suspected the Templars of heresy, and in 1272 a Council of the Church declared the entire Order to be urgently in need of reform. Nothing was done until 1307, when the King of France, Philip le Bel, launched a persecution of the Templars that finally resulted in the complete suppression of the Order on the grounds that it was deeply infected with sodomy, bestiality and, worst of all, heresy.

Between 1307 and 1314 there were a whole series of Templar trials at which individual Knights were charged with almost every possible offence against the laws of God and man. There were, however, five offences included in almost all the indictments:

(1) The administering of the sacrament of penance by a layman.

(2) Buggery and the use of the anal kiss.

(3) The defiling of the Crucifix by spitting, urinating or trampling upon it.

(4) The worship of an idol named Baphomet, usually described as being either a skull, a human head, or three heads.

(5) The omission of the words of institution

(Hoc est corpus meum

etc.) from the Mass.

The first accusation is an odd one, but it does seem to link the Templars with the practices of the Albigensians and other mediaeval Manichee groups. The same is true of the second charge for, rightly or wrongly, the Church believed sodomy to be intimately associated with dualistic heresy—indeed the word “bugger” is derived fron the Bogomil heretics who were particularly numerous in mediaeval Bulgaria. As for the anal kiss this was, according to the confessions of the accused Knights, given at the initiation of a new member of the Order and was exchanged between the candidate and his Preceptor.

1

Rationalistic explanations of the third accusation were given by historians of the last century. Some claimed that the candidate was ordered to trample on the Crucifix so that he might prove his Christian fortitude by refusing to obey. Others suggested that defiling the Crucifix was an indication of the Order’s loathing of the instrument of Christ’s suffering. Both explanations fail; the first because in all the Templar trials there are only two records of a candidate defying the order, the second because, if true, it would in itself be a proof of heresy—to regard the Cross, the instrument of the triumphant redemptive death of Christ, with hatred would have been indicative of a Docetic Christology, not Catholic Christianity.

The fourth accusation is the most curious. The suggestion that the name Baphomet was a corruption of Mahomet has been frequently made but is almost certainly incorrect; mediaeval Inquisitors may have been ignorant of the finer points of the religion of Islam, but not so ignorant that they were unaware of the name of its Prophet! The most interesting explanation of the origin of the name was given by the nineteenth-century orientalist Joseph Von Hammer. His arguments, and the evidence he based them upon, were splendidly summarised by J. C. Hotten and Thomas Wright in their

Essay on the Worship of the Generative Powers in the Middle Ages:

“Von Hammer has described twenty-four images … which it must be acknowledged answer very well to the descriptions of their idol given by the Templars … Most of them have beards and tolerably fierce countenances. Among those given by Von Hammer are seven which present only a head, and two with two faces, backwards and forwards, as described in some of the depositions.

2

These two appear to be intended for female heads … The most interesting of the coffers described by Von Hammer … is of calcareous stone, nine inches long by seven broad, and four and a half deep, with a lid about two inches thick. It was found in Burgundy. On the lid is sculptured a figure, naked, with a head-dress resembling that given to Cybele in ancient monuments, holding up a chain with each hand, and surrounded with various symbols, the sun and moon above, the star and the pentacle below, and under the feet a human skull. The chains are explained by Von Hammer as representing the chains of aeons of the Gnostics. On the four sides of the coffer we see a series of figures engaged in the performance of various ceremonies … which Von Hammer considers as belonging to the rites of the Gnostics and Ophians. The offering of a calf figures prominently among these rites… In the middle of the scene on one side, a human skull is seen, raised upon a pole. On another side an androgynous figure is represented as the object of worship of two candidates for initiation, who wear masks apparently of a cat, and whose form of adoration reminds us of the kiss enacted at the initiation of the Templars. This group reminds us, too, of the pictures of the orgies in the worship of Priapus, as represented on Roman monuments … on an impartial comparison we can hardly doubt that these curious objects… have been intended for use in some secret and mysterious rites, and the arguments by which Von Hammer attempts to show that they belonged to the Templars seem at least to be very plausible. Several of the objects represented upon them, even the skull, are alluded to in some of the confessions of the Templars … There is, however, another circumstance connected with these objects which appears to

furnish an almost irresistible confirmation of Von Hammer’s theory. Most of them bear inscriptions, written in Arabic, Greek and Roman characters.… the coffers … contain a nearly uniform inscription in Arabic characters which, according to the interpretation given by Von Hammer, contains a religious formula. The Arabic characters, he says, have been copied by a European, and not very skilful, carver, who did not understand them, from an Eastern original, and the inscriptions contain corruptions and errors which either arose from this circumstance, or,… may have been introduced designedly, for the purpose of concealing the meaning from the uninitiated. A good example of this inscription surrounds the lid of the coffer found in Burgundy … the word under the feet of the figure … is nothing more than the Latin

cantate

expressed in Arabic letters. The words with which this

cantate

begins are written above the head of the figure …

Jella Sidna

, i.e. O God, our Lord! The formula itself commences on the right side, and the first part of it reads

Houve Mete Zonar feseba B. Mounkir teaala tiz

. There is no such word in Arabic as

mete

, and Von Hammer considers it to be simply the Greek word

metis

, wisdom … He considers that the name Baphomet is derived from the Greek words

Baphe Metis

, i.e. the baptism of Metis, and that in its application it is equivalent with the name Mete itself. He has further shown, we think conclusively, that Baphomet, instead of being a corruption of Mahomet, was a name known among the Gnostic sects in the East. The rest of the formula is given on the other side of the figure, but as the inscription here presents several corruptions, we will give Von Hammer’s translation … of a more correct copy of the formula inscribed on a bowl or goblet preserved in the museum at Vienna … ‘Let Mete be exalted, who causes things to bud and blossom! He is our root; it (the root) is one and seven; abjure (the faith) and abandon thyself to all pleasures.’ ”