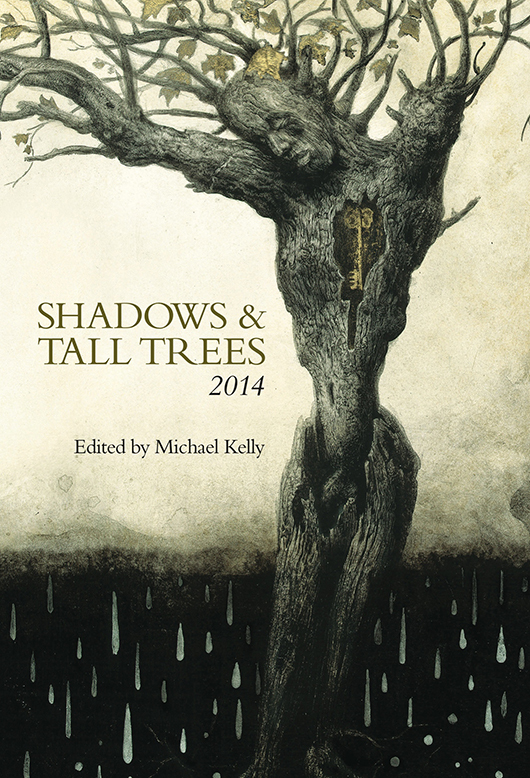

Shadows & Tall Trees

Read Shadows & Tall Trees Online

Authors: Michael Kelly

T

ALL

T

REES

Spring 2014

E

DITOR

| Michael Kelly

C

OPY

E

DITOR

/

P

ROOFREADER

| Courtney Kelly

An Imprint of

ChiZine Publications

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

To Assume the Writer’s Crown: Notes on the Craft

Eric Schaller

Michael Wehunt

Robert Shearman

Charles Wilkinson

Kaaron Warren

Tara Isabella Burton

F. Brett Cox

V.H. Leslie

R.B. Russell

Myriam Frey

Conrad Williams

The Vault of the Sky, The Face of the Deep

Robert Levy

Christopher Harman

Alison Moore

Ralph Robert Moore and Ray Cluley

C.M. Muller

Writings Found in a Red Notebook

David Surface

DITOR’S

N

OTE

Welcome to volume 6 of Shadows & Tall Trees. If you’ve read any of the previous issues you’ll notice we’ve moved away from our journal format to a yearly trade paperback and eBook anthology. We’ve doubled our size, bringing you twice the amount of fiction, all, we trust, to our usually high standards.

Alas, I had planned on running some non-fiction but did not receive any suitable submissions.

The other big news is that Undertow Publications, home to

Shadows & Tall Trees

, and the

Year’s Best Weird Fiction

, is now an imprint of ChiZine Publications, and will be available worldwide through ChiZine’s established distribution channels. If all goes well, you may see more titles from Undertow Publications.

Anthologies are a hard sell. I love short stories. I love the way they whisk you away to another place. I love how compact short stories are. You can experience so much in 5 minutes, 20 minutes, what have you. I love their language, their diversity, and the way they convey so much in so little words. They are magic. They are, to me, the perfect art form. I will always champion the short story. It’s a lot of work to put together an anthology. But it’s worth it.

Here’s to many more years of magic.

Michael Kelly

April, 2013

O

A

SSUME THE

W

RITER’S

C

ROWN

:

N

OTES ON THE

C

RAFT

E

RIC

S

CHALLER

NTRODUCTION

B

ookcases proliferate in my home. I could write

house

rather than

home

but, to me—and I think you and I may be alike in this regard—books define my

home

. One of my bookcases is a magnificent construction of bird’s-eye maple. Another is of oak: warm wood with swinging glassed doors. These represent my Platonic ideal of book collecting. Most of my bookcases, sadly enough, are of the

requires-some-assembly

variety and, as soon as one bookcase is filled, I assemble another. There is never enough space. Books pile on their shelves, on my couch, on the floor. My cats knock over the books and piss on them.

I’ll let you in on a secret. Although I call myself a writer of fictions—my publications confirm this assessment—much of my library consists of non-fiction. The first book I bought, at the innocuous age of six, was a biography of Cortez. Cortez the Killer, as Mr. Neil Young would have it. One of my most influential books was

Two Little Savages

, which under the guise of a children’s tale has much to instruct on wilderness lore. Reading that book, I painted my face with blue clay, deciphered and followed animal tracks, and devised snares to trap pigeons. The following Christmas, my parents gifted me with a wonderful book on knot tying. I still own all three of these books.

But it is not to discuss my facility with knots that I began this essay; rather it is on the craft of writing itself. The secret within the secret I now confess is that my bookshelves contain as many books on writing as they do writings themselves. I exaggerate, but the truth is that I have always loved the non-fiction that proliferates around fiction as much, if not more, than the fiction itself. In this essay, I will share with you some highlights of what I have learned over the years. Relax. Pour yourself a drink. The next few minutes are ours and ours alone. Writing is not all fun and games, but let’s pretend for the moment that it is.

IRST

T

HINGS

F

IRST

In my estimation there are but two classes of writers: those who write and those who don’t. “But how can anyone be a writer if they don’t write?” you of the first contingent assuredly exclaim. By their own proclamation is my answer. Moreover, I believe this second contingent is in the majority. They are the jealous fools, who upon hearing you have written a story or two, perhaps a dozen, in my case over a hundred, none of which they have read, will declare themselves writers of equal merit, if only. . . These two words (“If only . . .”) are the key to their thwarted ambition. If only they had not been engaged in more lucrative enterprises. If only they had not raised a family. If only they had found the time to set their words to paper.

If only . . .

These wasters have assumed the writer’s crown without any more exertion than the flapping of their puerile lips. Run, I say, should you meet such a

writer

, run with all alacrity and hide. Above all, do not show them this essay, for they will claim the ideas for their own and, never recognizing the contradiction, scoff that you should sympathize with it.

HE

C

AGE OF

W

ORDS

The key to successful fiction, its heart, its soul, is in the character. Some imbeciles will state that a genre, like science fiction, is more about the idea than the character. But an idea without a character is a bodiless brain. Even the most idea-driven science fiction employs characters to carry the reader through the story.

How then to best capture a person in words?

There is the obvious possibility of describing the character’s physical features. For instance, a woman—blonde hair, blue eyes, tanned—so close to a cliché that you could be arrested for artistic delinquency. Instead, how about: hair a sun-bleached blonde, eyes the silvery-blue of beach holly, skin a deep natural tan. This description suggests something of the woman’s history but at the expense of a truckload of adjectives. All the reader now knows is that the character spends a carcinogenic amount of time in the sun. Let me give you the scientific name for that variety of cancer:

longinquus

. That’s Latin for

boring

.

Physical description is wasted unless it is freighted with emotion. David Morrell, in

Lessons from a Lifetime of Writing

, advises writers to emphasize “the

effect

that a character’s appearance has on others.” To revisit our example: the woman, her blonde hair disheveled, her skin slick with sweat, turned at my approach, her eyes hunted . . .

Hunted? Haunted, I meant.

HE

P

ATHETIC

F

ALLACY

This phrase, coined by John Ruskin, was intended as a pejorative against attributing human emotions to nature, of having the universe sentimentally reflect the state of your characters. In my opinion, Ruskin’s concern points to the effectiveness of this technique, none having employed it to more success than Edgar Allan Poe (“The Fall of the House of Usher”). Let’s give it a shot with our female character. Note how I use this technique to capture her essence:

Mary—for so I shall call my female character—has gone for a run on a blustery October afternoon. She always runs when she’s troubled. What has happened? She’s thinking about her boyfriend and the gossip that he was seen at the movies with another girl that looked a lot like her. Mary feels a raindrop on her cheek and glancing up sees clouds clotting darkly above the rooftops. How could he cheat on her? How could he touch another girl? The wind gusts, her flesh prickles, and she wishes she’d worn sweats instead of shorts. There’s not far to go, just a shortcut through a wooded lot. She gulps air. Smells evergreen. A bird trills, and for the briefest of moments she smiles, a toothy smile at this wonderful inconsequential song in the face of the coming storm. Where is that bird? Why the hell did he do what he did with that girl? Why did he fondle her secret places? There’s a slippery movement beneath the pines and then a tug at Mary’s shoulder. Mary lashes out. She stumbles. Her hand tears at leaves. Wet fragments stick to her fingers. She’s on her knees. Thunder cracks and she’s dragged forward. Her cheek smacks metal. Her nose, erupting blood, is engulfed in a carpet that reeks of mildew and cat piss. She screams. Too late. The door of the van slams. Trapped.

HE

B

ARE

N

ECESSITIES

Frank O’Connor wrote, “There are three necessary elements in a story—exposition, development, and drama. Exposition we may illustrate as ‘John Fortescue was a solicitor in the little town of X’; development as ‘One day Mrs. Fortescue told him she was about to leave him for another man’; and drama as ‘You will do nothing of the kind,’ he said.”

This is, in fact, the universal struggle of the author with the written word, with his or her characters. Consider the following:

“The author lived in an oppressively large farmhouse at the end of gravel road.

“One day he decided to write a story.

“‘You’ll do nothing of the kind,’ Mary said.”

HE

W

ORST

A

DVICE

David Morrell describes how he once heard a teacher, intending to simplify the writing process, exhort his students to imagine their stories as movies and to then write what they saw. A fool teaching fools! The limitation of this advice is that it only engages the sense of sight. Writing grants you the supernatural ability to spy inside a character’s mind, revealing thoughts and experiences, and engage

all

the senses. Let’s return to my character,

our

character, and bring this sensory information into play.

N

E

XERCISE

There is just one rule for this exercise: you may not use the sense of sight for your description. Imagine yourself in a darkened room, a basement. I recommend that you try this for real. You descend the stairs, running your hand along the wall to maintain balance. Feel the texture. Describe it. Do the stairs creak? What is the smell of the basement? How is it floored: poured concrete, gravel, barren earth? This is called “Setting the Scene.”

Now, to introduce some drama: stepping out onto the basement floor, you turn. What was the sound you heard? A moan. A distinctively feminine moan, in fact. Does this excite you? You come across the body of a woman. Is she naked? You have only your non-visual senses to inform this decision. Her feet, which you encounter first, are certainly bare.

What’s this twined around her ankles? Something hard, serpentine: the plastic-coated metal of a bicycle chain. The woman is bound to a chair. What kind of chair? You can determine this through your senses of touch, smell, and yes, even taste.

The woman is cold, as one must expect of a body without the comforting benefit of clothes, but just as assuredly alive. Her skin prickles at your touch. Her calf muscles tighten yet she does not struggle. Her breaths come short and shallow like submerged hiccups. The skin on her legs tastes of salt as if she had been swimming, or running. Her knees are skinned. Her pubic thatch, to your surprise, is shaved, scented, as if in preparation for a boyfriend.

For you?

You avoid her breasts. You don’t want her to get that idea. Nevertheless when your hand trails past her shoulder, brushing her neck for the barest instant, she moans again. You can’t tell whether from fear or desire. Her cheek shivers. Note the texture of her skin: the fine hair (the cliché of peach fuzz comes to mind), the puffiness, the

fleshiness

, all ending abruptly at the bony lower orbit of her eye. She has, you discover, clenched her eye lids shut. Even though it is dark. Even though she cannot see you. She has not, in fact, ever knowingly observed you.

Mary is not entirely naked as it turns out. She wears a misshapen hat: a bird made of felt fastened to her head with a stretchy band that runs under her chin. The hat was probably once a cat’s toy but has been re-purposed. It smells of cat pee, that’s for certain.

RITE

W

HAT

Y

OU

K

NOW

One of the most limiting writing recommendations ever set to paper, if interpreted literally. Do you want to produce nothing but thinly disguised autobiographies? Consider a re-interpretation: write from the emotions that you know. Write, as so many books on my shelves implore, from what you care about.

For me, it always returns to a woman, a girl from my high school. Her name was Mary (not her real name) and she had the most gorgeous smile. I think she needed braces, but braces would have ruined that smile. Her smile appeared without preamble in response to the school heaters burping in winter, the rhymes of children jumping rope, the crackle of the PA system. It could light up the room, as they say. Part of me loved her, but I had never pursued a woman before. I sat two seats behind and across the aisle from her on the school bus. Sometimes she wore a red sweater. On those days she rhythmically pressed her thighs together, revealed only by the tension in her legs. I imagined myself as her. I imagined how the cloaked space between her legs felt in response to those rhythms.

Then I dreamed of Mary. Initially she was how I knew her: sweet, innocent, smiling. But she changed. She devolved. Have you ever seen the Bugs Bunny cartoon in which skinny, wise-cracking Bugs devolves into a burly Paleolithic version of himself? Something similar happened with Mary. In my dream, she became coarse and broad, hairy and hulking. Bigger than me. After that, I could never look at Mary the same way again.

In every story since then, I’ve tried to infuse my female characters with that initial element of desire I felt for Mary, and I’ve tried to avoid the subsequent revulsion. On the first score I’ve had some success. On the second, perhaps less.

IALOGUE

I

Character: Why are you doing this to me?

Author: (no answer)

HE

N

ARRATOR

Who to choose as the narrator for your tale? The girl? She may scream from blind fear until she is hoarse. She doesn’t know that she is locked in a basement far from town and the chances she will be heard are slim to none (and slim has already left town). This dawning realization can be communicated from her point of view. But how much more damning if the narrator should be someone else, unnamed, who can describe the same scene from a contrasting viewpoint. Black humour can be effective here, especially when the victim is of limited perception, a girl whose ideas of horror are blinkered by some appallingly bad movies. “Is the key to the lock behind my eye?” she asks. There is of course no answer, and the reader is left wondering if the girl will, in fact, gouge herself blind on the chance that this will illuminate the basis for her captivity.

A remark about Oedipus would be apropos, but would be lost on our character. Hence the silence of the narrator with regards to the victim. But not in regards to you, the reader, who one hopes will understand (relish?) the reference.

One of my favourite stories is by Kipling, the most black-humoured piece I have ever read, and one of the most instructive. The story is called “The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot.” It is not frequently reprinted, but it does appear in

The Oxford Book of Short Stories

(1981 edition), as chosen by V. S. Pritchett. “Her husband after two years took to himself another woman, and passed out of Badalia’s life, over Badalia’s senseless body; for he stifled protest with blows.” After that it goes from bad to worse for Badalia, ending in the tragedy of her death. Readers—it’s a fact—do not like weak-willed characters that are buffeted by events like tissues in a purse. However, under the guise of humour, any crime may be committed with impunity.