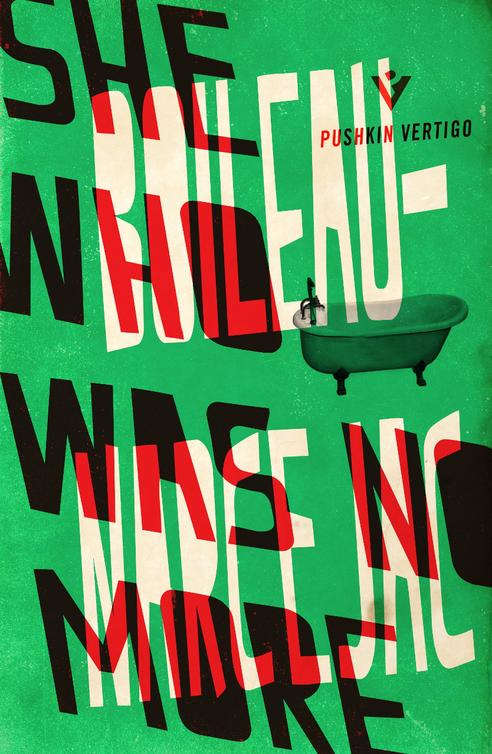

She Who Was No More

Read She Who Was No More Online

Authors: Pierre Boileau

Whose dark or troubled mind will you step into next? Detective or assassin, victim or accomplice? Can you tell reality from delusion, truth from deception, when you’re spinning in the whirl of a thriller or trapped in the grip of an unsolvable mystery? You can’t trust your senses and you can’t trust anyone: you’re in the hands of the undisputed masters of crime fiction.

Writers of some of the greatest thrillers and mysteries on earth, who inspired those who followed. Writers whose talents range far and wide—a mathematics genius, a cultural icon, a master of enigma, a legendary dream team. Their books are found on shelves in houses throughout their home countries—from Asia to Europe, and every where in between. Timeless books that have been devoured, adored and handed down through the decades. Iconic books that have inspired films, and demand to be read and read again.

So step inside a dizzying world of criminal masterminds with

Pushkin Vertigo

. The only trouble you might have is leaving them behind.

‘Can’t you keep still for a moment, Fernand?’

Ravinel halted in front of the window and drew the curtain to one side. The fog was getting thicker, forming yellow halos round the clusters of lights on the quay and green ones round the lamp posts along the roadway. Sometimes it thickened suddenly, drifting past in wreaths of smoke, at others it turned into a fine drizzle of glistening drops. Bits of the

Smoelen

’s forecastle, the portholes lit up, would come into view for a moment and then be blotted out. Now that Ravinel was standing still he could hear music from a record player. He could tell it was a record player because each piece lasted about three minutes, after which there was a pause while the record was changed. The sound came from the

Smoelen

.

‘I wish it weren’t there,’ muttered Ravinel. ‘Anyone on deck might see her coming. If they saw her enter the house…’

‘Nonsense,’ answered Lucienne. ‘Mireille won’t do anything to make herself conspicuous. Besides, it’s a foreign ship. Why should foreigners take any notice of her?’

With his sleeve he wiped the window that had become misty with his breathing. Looking out over the railings of the tiny front garden, he could see to the left a stippled line of pale lights and strange constellations of red and green ones, the former like the candles flaming at the far end of a church, the latter phosphorescent as fireflies. It was quite easy for

Ravinel to follow the curve of the Quai de la Fosse, to pick out the semaphore on the old Gare de la Bourse, the light on the gate of the level crossing, the lantern that hung on the chains which at night closed the passage to the transporter bridge, and the anchor lights of the

Cantal

and the

Cassard

. On the right, another quay began, the Quai Ernest-Renaud. The street lamps were reflected by the wet pavements and railway lines. On board the

Smoelen

the phonograph was playing Viennese waltzes.

‘She’ll take a taxi,’ said Lucienne. ‘At any rate to the corner of the street.’

Ravinel dropped the curtain and turned round.

‘No she won’t,’ he muttered. ‘She doesn’t throw money around like that.’

Another silence. Ravinel started pacing up and down the room again. Eleven steps between the window and the door. Lucienne was filing her nails. From time to time she held her hand towards the light which hung from the ceiling and turned it this way and that like some precious object. She had kept her coat on, though she had insisted on his changing into a dressing gown, taking off his collar and tie, and putting on his slippers.

‘You see, you’ve just come in. You’re tired and have changed into some comfortable clothes before sitting down to your supper… Got it?’

Oh yes, he understood all right. Only too well, with a sort of desperate clarity of mind. Lucienne thought of everything! And when he started to get the tablecloth out of the sideboard drawer, she pulled him up promptly in that husky voice of hers which was accustomed to giving orders.

‘No. You don’t want a tablecloth. You’ve just come in. You’re all alone and can’t be bothered to lay the table properly. You just picnic on the oilcloth.’

She had herself put a knife and fork for him. The slice of ham, still in its paper, she had thrown carelessly between the bottle of wine and the carafe of water. An orange stood on the box of Camembert.

‘Quite a pretty picture!’ he mused. ‘A still life.’ And he stood gazing at it for a while, frozen, unable to move, his hands sweating.

‘There’s something lacking all the same,’ remarked Lucienne. ‘Let’s see… You change… You’re going to have supper—all alone… You’ve no wireless to switch on… There! I have it! You glance through your day’s orders. It’s only natural.’

‘But I assure you—’

‘Hand me your dispatch case.’

On a corner of the table she spread out some typewritten sheets of paper at the head of which was printed a fishing rod and a landing net crossed like swords and the name of the firm he worked for:

Maison Blache et Lehuédé, 145, Boulevard de Magenta, Paris

.

It was then twenty past nine. Ravinel could have related minute by minute everything they had done since eight o’clock. First of all they had inspected the bathroom, making sure everything worked properly so that there was no chance of a hitch at the last moment. Fernand had wanted to fill the bathtub then and there, but Lucienne had objected.

‘Use your brains. She’ll want to look over the place and she’d wonder what the water was doing there.’

They nearly had an argument about it. Lucienne was in a

bad temper. Despite her outward coolness, you could see she was strung up and anxious.

‘My poor Fernand! One might think you didn’t know her. After five years!’

Which wasn’t so far from the truth. Did he know her? He wasn’t sure. It wasn’t as easy as all that to know a woman. You sat opposite her at meals. You went to bed with her. You took her to the movies on Sundays. You saved up money to buy a little house on the outskirts of Paris. Good night, Fernand! Good night, Mireille! She had cool lips and tiny freckles at the base of her nose, but you only noticed them when you kissed her. Light as a feather when you picked her up. But, if she was thin, she was strong and wiry. A nice little thing. Insignificant, however. Why had he married her? Can anyone really answer a question like that? You’re thirty-three. You’ve reached the marrying age. You’re sick to death of hotels and cheap restaurants. It’s no fun being a traveling salesman. When you’re working out of Nantes all week, it’s nice to go back at the weekend to that other little house at Enghien and find a smiling Mireille sewing at the kitchen table.

Eleven steps from the door to the window. A peep past the curtain. The three lit-up portholes in the

Smoelen

’s bow were lower now. The tide must be ebbing. A freight train from Chantenay trailed past, the wheels creaking, and one after another the roofs of the cars slid slowly under the semaphore in a mist of fine rain. An old German caboose brought up the rear with a red light hanging above the buffers. When it had passed, the

Smoelen

’s record player was audible once more.

At a quarter to nine they had each had a small brandy

to keep their courage up. It was after that that Ravinel had changed into his slippers and dressing gown. The latter had several holes burned in it by sparks from his pipe. Lucienne had arranged the things on the table. Silently. That was the trouble: they could find nothing to talk about. The train from Rennes had gone by at nine sixteen, sending beams of light sweeping across the ceiling. It seemed a long time before the rhythm hammered out by its wheels finally died away.

The train from Paris wasn’t due till ten thirty-one. Another hour to wait! Lucienne went on silently filing her nails. The alarm clock on the mantelpiece ticked breathlessly. Occasionally something went wrong with the works. Its pulse would miss a beat, then right itself, though continuing on a slightly different note.

For a moment their eyes met. Ravinel took his hands out of his pockets and, clasping them behind his back, resumed his pacing, trying to obliterate the vision of this other Lucienne who was a stranger to him, a hard-featured woman with a scowl on her forehead. It was folly, what they were about to do, absolute folly… Unless…

Unless, for instance, Lucienne’s letter had gone astray. Or Mireille might be ill, or…

He slumped down on a chair at Lucienne’s side.

‘I can’t go on with it.’

‘What’s the matter? Afraid?’

He bristled at once.

‘Afraid! No more than you are.’

‘Then everything’s all right.’

‘It’s only this waiting that gets me down. As a matter of fact I think I’ve got a temperature.’

She felt his pulse with her firm, expert hand. She made a face.

‘You see! I’m getting something. And if I fall ill, that’ll make a nice hash of things.’

She stood up, slowly buttoned her coat, then casually ran a comb through her dark curly bobbed hair.

‘What are you doing?’ stammered Ravinel.

‘I’m going.’

‘No. You mustn’t.’

‘Then pull yourself together. What is there to be afraid of?’

Were they to go over all that again? For the hundredth time? As if he didn’t know Lucienne’s arguments by heart! For days and days he’d turned them over, studying them one by one. He hadn’t jumped at the idea—far from it!

His mind went back to Mireille. There she was, ironing in the kitchen, stopping now and again to stir something that was simmering in a saucepan. How well he had lied! Almost without effort.

‘I ran into Gradère today. You must have heard me speak of him. No? Really? We did our military service together. He’s doing insurance work now. Seems pretty prosperous.’

Mireille was ironing some underpants, the point of the iron going deftly round each button, leaving a smooth white trail from which rose a trace of steam.

‘He kept at me for a long time, telling me I ought to take out some life insurance. At first I didn’t take him very seriously. After all, you know what they’re like. They’re thinking of their rake-off, and you can’t blame them. It’s only natural… In the end, however, I had to admit there was something in it.’

She put the iron down on its stand and switched off the current.

‘You see, in my line of business, there aren’t any widow’s pensions. And when you think of all the traveling I have to do… Accidents are only too easy. And if that happened, what would become of you? We’ve no savings to speak of.

‘So in the end I let Gradère quote me rates. The premium isn’t too stiff. Not when you consider the advantages. For if anything happened to me, you’d get a couple of million francs in cash.’

It sounded pretty good, that. A proof of his affection. Mireille was quite bowled over.

‘Really, Fernand. You’re so kind…’

But the hard part was still to come—to wheedle Mireille into taking out a similar policy for his benefit. That was a delicate subject. How was he to raise it?

He didn’t have to. The wretched Mireille spared him the trouble.

‘I’ve been thinking it over,’ she said a week later, ‘and I’ve come to the conclusion my life ought to be insured too. After all you never can tell who’s going to live or who’s going to die. And you’d be in a pretty pickle with no one to look after you.’

He had protested. Of course, he had to. But no more than was absolutely necessary, and in the end she had signed on the dotted line. That had been two years ago.

Two years. They’d had to wait that long. It was stipulated by the insurance company that if the insured person committed suicide within two years the contract was void. And you never knew what verdict might be brought in at an inquest. Lucienne, at any rate, was not the sort of person to take a risk like that. To go to so much trouble and then perhaps get nothing in the end!

Yes, it had all been carefully thought out, and a hundred other details too. In two years you can study a problem pretty thoroughly. No. There was nothing to be afraid of. Ten o’clock.

Ravinel got up from his chair and joined Lucienne who was standing at the window. The street was empty, glistening with wet. He slipped his hand under his mistress’s arm.

‘Don’t take any notice. I can’t help it… As soon as I start thinking…’

‘Don’t think.’

They stood side by side, motionless, the intense silence of the house weighing on their shoulders, behind them the alarm clock ticking feverishly. The portholes of the

Smoelen

were like pale full moons, growing still paler as the mist thickened. Even the phonograph seemed muffled by it. Ravinel hardly knew whether he was alive or dead. As a small boy it was like this that he had visualized the next world—a long wait in a fog. An interminable, terrifying wait. If he shut his eyes, it felt as though he were falling—a giddy, awful feeling, yet somehow pleasant at the same time. His mother would shake him.

‘Whatever are you up to?’

‘Nothing. Just a game.’

When he opened his eyes, he felt lost for a moment and vaguely guilty. Later on, when he was being prepared for his first communion the Abbé Jousseaume had questioned him.

‘Any wicked thought? Any impure ones?’

And he had at once thought of this fog game. Obviously it was something forbidden. Impure, no doubt. Yet he had never altogether given it up. In fact he had even developed it to the point where he himself seemed to evaporate and become part of the fog. For instance, on the day of his father’s funeral. It

really had been foggy then, so thick that the hearse had looked like a sinking ship. And he had clearly had the feeling they were already in another world. It wasn’t sad. Nor was it exactly gay. Just a supreme peace… On the other side of a forbidden frontier…

‘Twenty past ten.’

‘What?’

Ravinel started, finding himself once again in the poorly furnished, dimly lit room, standing beside a woman in a black coat who took a small medicine bottle from her pocket.

Lucienne! Mireille!

He took a deep breath. He was back on this side of the frontier now.

‘Come on, Fernand. Rouse yourself. Here, give me the carafe.’

She spoke to him as though he were a boy. That’s what he loved in her, in this Dr. Lucienne Mogard. Funny, wasn’t it? She was his mistress. At moments it seemed quite incredible, almost monstrous.

Lucienne emptied the bottle into the carafe and gave the mixture a shake.

‘Take a sniff. No smell whatever.’

Ravinel sniffed. She was right. The stuff was absolutely odorless.

‘You’re sure it’s not too strong?’

Lucienne shrugged her shoulders.

‘If she drank the lot, perhaps. Though even that’s doubtful, and in any case she won’t. She’ll have a glass, two at the most. Trust me to know how it works. She’ll fall asleep almost at once.’

‘And—if there’s a post-mortem—they won’t find any trace?’

‘My dear Fernand, as I’ve told you before, this isn’t a poison. It’s just a soporific and it’s assimilated instantly. Now, you sit down at the table…’

‘Already?’

They both looked at the clock. Twenty-five past ten. The Paris train was approaching Nantes. It should now be crossing the Bottereau yards and in five minutes it would be in the station. Mireille would walk quickly. It wouldn’t take her more than twenty minutes. Somewhat less if she took the tram as far as the Place du Commerce.