She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (19 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

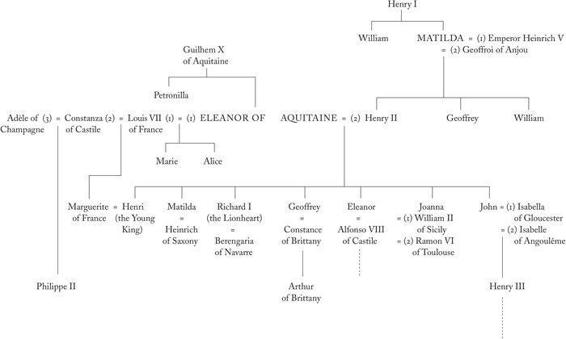

The implications of that decision are clear in the Latin verses later inscribed on her grave: ‘Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring, here lies the daughter, wife, and mother of Henry.’ Her son’s triumph was the vindication of everything she had done; but the price to be paid for that victory was her disappearance between the lines of her own epitaph – a tacit acceptance that a female heir to England’s throne, unlike her male counterpart, could not expect to rule for herself. The question would not arise again for four hundred years, until the agonising death of a fragile boy in 1553, and in the meantime any woman who aspired to the exercise of power in England – most immediately Matilda’s formidable daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Aquitaine – could hope to achieve it only by negotiating the roles of daughter, wife and mother that, etched into Matilda’s tomb, came to define her career in retrospect.

But, if Matilda’s last resting-place framed her achievements only in relation to her father, husband and son, one of those men was unwilling to do the same. Her son would become one of the most exceptional rulers in medieval Europe, and throughout his turbulent life this volatile, powerful monarch acknowledged the political legacy of his courageous and controversial mother by calling himself ‘Henry FitzEmpress’.

An Incomparable Woman

1124–1204

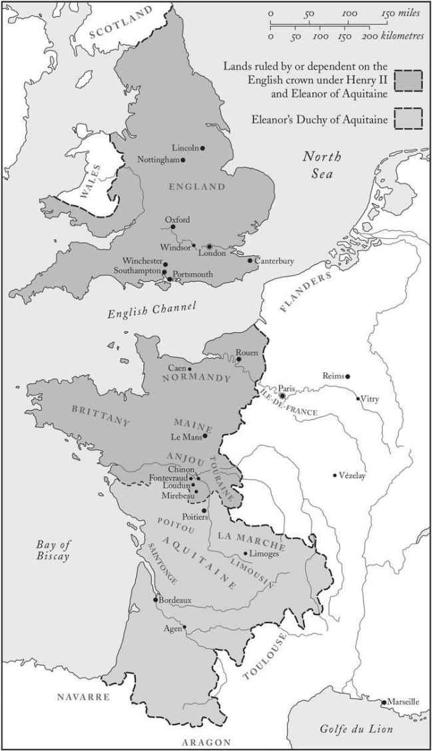

A casual observer at Henry II’s court in September 1166 might have been forgiven for thinking that Eleanor of Aquitaine was the most conventional of queens. A great heiress, famed for her beauty and her agile mind, she had brought her royal husband a rich inheritance that stretched from the green valleys of the Vienne river, where soft light danced on stately water as it flowed toward the Loire, to the foothills of the Pyrenees, where a stronger sun struck towering crags of granite and limestone.

And, along with the landscape and liegemen of her vast duchy of Aquitaine, Eleanor had given her husband a large brood of heirs to inherit his growing empire. Seven months pregnant now with the king’s eighth child, she had played to perfection the role of dutiful consort, spending enough time with her husband to ensure a succession of pregnancies – she gave birth five times in the first six years of their marriage alone – while also, so far as her repeated confinements allowed, providing a figurehead for his government in England during his long and frequent travels through his lands in France.

If her role as royal wife and mother was utterly conventional, so too is the fact that the chroniclers recorded no pen-portrait of Eleanor to match their detailed descriptions of her husband and king. Henry exerted a particular fascination on the men who recorded the events of his reign. In part at least, this is because a significant number of the contemporary writers whose works have survived – Walter Map, Gerald of Wales, Herbert of Bosham, Roger of Howden and Peter of Blois – served in one capacity or another as clerks at his court, and therefore observed his charisma, his idiosyncrasies and his extraordinary capabilities at close range.

It remains clear, however, that the sheer magnetic force of his personality reached far beyond the confines of his household.

He had inherited the sturdy physicality of his royal grandfather and namesake, Henry I: he was neither tall nor unusually short, but broad and stockily muscular, thick-necked and square-chested. The solidity of his powerful frame blurred easily into fat, which he held at bay not only by the frugality with which he ate and drank, but also by virtue of the relentless energy that had been so marked in his grandfather, a quality which, in the younger man, became an almost pathological restlessness. He was a ‘human chariot dragging all after him’, wrote Herbert of Bosham, a cultured dandy whose personal style had little in common with that of his strenuous king. On his frequent military campaigns Henry scarcely paused to eat or sleep, his bowed legs and hoarse voice testifying to the hours he spent in the saddle. But times of truce did not bring peace to his household. Instead, he rose before dawn to satisfy his compulsive obsession with hunting, returning dusty and blood-smeared from the kill to spend his evenings still on his feet, reducing his courtiers – who were not permitted to sit while their king remained standing – to a state of exasperated exhaustion.

His leonine colouring – red-gold hair and ruddy, freckled face, offset by expressive blue-grey eyes – was a legacy from his Angevin father, although he did not share the physical beauty for which Geoffroi had been celebrated in his youth. Henry’s bulk, his closely shorn hair and his plain, practical clothes gave him a physical appeal that derived from his commanding vitality rather than any more obvious glamour. He was driven and ambitious, like his father, but his quick, scholarly mind seems more likely to have come from his remarkable mother, Matilda. Like her, this man of tireless action was entirely at home among intellectuals and academics: ‘… with the king of England’, wrote Peter of Blois, ‘it is school every day, constant conversation with the best scholars and discussion of intellectual problems’. He read voraciously, his memory was prodigious, and, though he expressed himself only in French and Latin, he knew something, Walter Map reported, of

‘all tongues spoken from the coast of France to the river Jordan’.

However, where Matilda’s public life was shaped by her self-control and carefully considered pragmatism, Henry was passionately emotional, a character of extremes and contradictions. He was unpretentious, patient and approachable, and possessed of unearthly calm in the face of crisis, yet capable of the most violent fits of rage. Court gossip (reported in 1166 to Archbishop Thomas Becket, once the king’s closest friend, now estranged and in exile) described one outburst of ferocious temper that left Henry screaming on the floor, thrashing wildly and tearing at the straw stuffing of his mattress with his teeth. He loathed betrayal in others, but was notorious for his willingness to break his own word without a second thought. He could be fierce or gentle, harsh or generous, and he contrived (without apparent contrivance) to be simultaneously an immovable object and an irresistible force.

The first hint that our observer of Henry’s court might get that Eleanor of Aquitaine was no conventional queen was the fact that she was a match, in personal as well as political terms, for this overwhelming, brilliant, bloody-minded king. Before she ever took her place at Henry’s side, she had had another life full of incident and experience. And the eventful pre-history of England’s queen was more than enough to show that the serene, swollen-bellied madonna of the autumn of 1166 was only one persona among many in the repertoire of an exceptional, unpredictable woman.

Eleanor was born probably in 1124, the first daughter of Guilhem, heir to the great duchy of Aquitaine. The court over which her family presided was dramatically different in style from the sober piety of the Anglo-Norman and German royal households in which Matilda had spent her childhood. At its head was Eleanor’s grandfather, Duke Guilhem IX, crusader, womaniser and poet of love and lust – the first of the troubadours, writing in Aquitaine’s native

langue d’oc

, whose verses have survived. William of Malmesbury, hundreds of miles away in England, recounted scandalous rumours of the duke’s provocative exploits and his sardonic wit: he ordered that his mistress’s portrait should be painted on his

shield, William reported with some relish, declaring that ‘it was his will to bear her in battle as she had borne him in bed’.

Such tales probably had their roots in garbled elaborations of Duke Guilhem’s songs, fiction turning into breathlessly reported fact as it travelled northward. But the truth needed little such embellishment. The duke’s long-suffering duchess, Philippa of Toulouse, eventually left him for a religious life at Fontevraud Abbey – a new double monastery founded in 1101 by the ascetic preacher Robert d’Arbrissel, where both monks and nuns lived under the direction, unusually, of an abbess – fifty miles north of the duke’s city of Poitiers. In Philippa’s place at his side, Guilhem installed the woman whose notoriety had reached as far as the cloisters at Malmesbury – she of the supposed shield-portrait, the wife of the lord of nearby Châtellerault, though her name is not known – and arranged a marriage between his lover’s daughter and his own eldest son.

That son and heir, who became Duke Guilhem X when his father died in 1127, was a less flamboyantly talented character, famous for his insatiable love of food rather than his poetry. He spent ten turbulent years at the helm of Aquitaine’s affairs before deciding, in 1137, to invoke the spiritual support of St James the Apostle by making a pilgrimage to his Galician shrine. (The saint’s hand, thanks to Matilda, was now an object of veneration at Reading Abbey, but his body was believed to lie beneath the great granite cathedral newly built in his honour at Compostela in north-western Spain.) If the saint responded to the duke’s prayers, however, it was to secure the welfare of his soul rather than his duchy. Guilhem was already seriously ill when he arrived at Compostela, and he died there on Good Friday 1137. His body was buried before the cathedral’s high altar, his pilgrimage transmuted into a permanent resting-place.

His death left his children orphans. His wife, Anor of Châtellerault, had died several years earlier, along with their only son, another Guilhem. Two daughters remained: Petronilla, the younger, and her elder sister, Eleanor, who had been named after

their mother – hence Aliénor, ‘another’ (in Latin,

alia

) Anor. The girls had been left at Aquitaine’s port city of Bordeaux under the distant guardianship of the French king, Louis the Fat, who was the duke’s nominal overlord. When reports arrived from Spain of Duke Guilhem’s death, Louis lay sick at his hunting lodge at Béthisy, north-east of Paris, exhausted by encroaching age and the physical strain of his obesity. But ill-health had not compromised his instincts as a king, and he responded with alacrity to the news that the fate of Aquitaine now rested on the slender shoulders of a thirteen-year-old girl. Eleanor should marry his son, the king declared, and he immediately despatched the prospective bridegroom, seventeen-year-old Louis, to Bordeaux with an imposing retinue which included the greatest noblemen in France as well as the king’s chief minister, Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, and hundreds of well-armed knights.

It was an abrupt and forceful courtship, but the political imperatives that lay behind it were too compelling to be ignored. For 150 years, it had been the ambition of the Capetian kings to turn their theoretical sovereignty over the great feudal lords of France – the dukes of Aquitaine prominent among them – into the reality of power. But old freedoms could not be so easily curtailed, and, despite three decades of King Louis’s shrewd and commanding rule, the area under the crown’s direct control remained limited to the Île-de-France, the ‘island’ around Paris bounded by the rivers Seine, Marne, Oise and Beuvronne. Now, however, marriage vows rather than military force promised to deliver Aquitaine into royal hands. And, for Eleanor and those who advised her, the prospect of a husband who would be king of France as well as duke of Aquitaine offered protection for her rights as the duchy’s heir, rights which would otherwise be rendered acutely vulnerable by her youth and her sex.