She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (57 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

Margaret was forty-one years old, and her life was over. For Edward, and for Louis of France and Charles of Burgundy, manoeuvring furiously for advantage in this changed political world, she was an irrelevance. In June rumours reached France that Margaret too had been assassinated, but Edward was by nature magnanimous rather than vindictive, and he had no need to pay her the political compliment of a violent death. Instead she remained a prisoner, at first in apartments at Windsor Castle and the Tower of London, and later – the king extending his easy generosity even to this bitterest of enemies – at Wallingford Castle forty miles west of London, in the gentler custody of her old friend Alice Chaucer, the dowager duchess of Suffolk, who had been kind to her when she had first left her family behind to embark on her future as England’s queen.

She had been a captive for four years when, in 1475, her fate constituted one of the detailed provisions of a peace treaty agreed at Picquigny between Edward and Louis. By its terms she renounced any claim she might notionally still have to rights or properties in England, and the French king agreed to ransom her person for a sum of £10,000. Free, but penniless and purposeless, she went to live quietly in her father’s lands of Anjou. She was at the château of Dampierre, overlooking the broad meanderings of the Seine, when she fell ill in the summer heat of 1482. She died on 25 August, her end scarcely noticed by the crowned heads of Europe, and was buried beside her father beneath the soaring arches of the cathedral at Angers.

Margaret was a woman of will and wit – ‘more wittier than the king’, noted one chronicler, although that was a backhanded tribute given the manifest limitations of her foolish, fragile husband. Denied the formal regency that she might have enjoyed in her French homeland, all her fierce energy was devoted to the task of impersonating, of reconstituting by other means, the royal will that her husband was incapable of providing. The magnitude of her role was evident to those who watched her at work: for Prospero di Camulio in 1461, for example, the battle of Wakefield was simply ‘the battle which the queen of England fought against the late duke of York’ – a description remarkable in its directness given that Margaret could not, and did not, set foot on the field of war.

But the magnitude of her role was its own undoing. In stepping forward to champion her husband’s cause, she exposed the composite authority she had constructed in his name to public view, and herself to vitriolic disapproval. The harder she fought – and fight hard she did, with an implacable and partisan tenacity – the more obvious were the tensions created by a French queen acting in the place of an incompetent English king. And, little by little, the power she could command fragmented and crumbled away. As an Italian in London noted as the conflict came to its height in 1461, ‘whoever conquers, the crown of England loses, which is a very great pity …’

That much became evident just eight months after her death. Edward’s conquering regime was carefully constructed and authoritatively led, but its roots were not yet deep. In April 1483, shockingly and suddenly, he succumbed to a stroke at the age of just forty, a golden boy bloated into dissolution; and his government collapsed into chaos. The twelve-year-old heir to the throne – the baby boy born to Edward and Elizabeth in the Westminster sanctuary – was deposed and murdered by Edward’s youngest brother and most trusted lieutenant, Richard of Gloucester. And the usurpation of Richard III, as the new king called himself, opened the door to a penniless exile named Henry Tudor, Jasper Tudor’s nephew, whose mother Margaret was the last of Henry VI’s Beaufort cousins – a tenuous connection to the royal line, but enough, amid the trauma of 1485, to rally an army. That summer Richard III lost his crown and his life at Bosworth Field, and Henry Tudor took his place as King Henry VII. It was the last act of the drama which had consumed Margaret’s life.

The boy in the bed lay at peace, his breathing stilled, his struggle finished at last. But the men who looked down at the disfigured body knew that theirs had just begun. Now, they faced the battle to control the accession of England’s first reigning queen.

Their initial task was to stop the news of what had happened from spreading beyond the walls of the bedchamber until the levers of power had been comprehensively secured. The same tactic had been adopted six years earlier when Edward VI’s father had died; then, deliveries of royal meals had continued for three days to the heavily guarded door behind which lay Henry VIII’s monumental corpse, until the person of the new king could be united with his principal councillors and the governmental machine at their disposal to proclaim the start of the new reign as a seamless fait accompli.

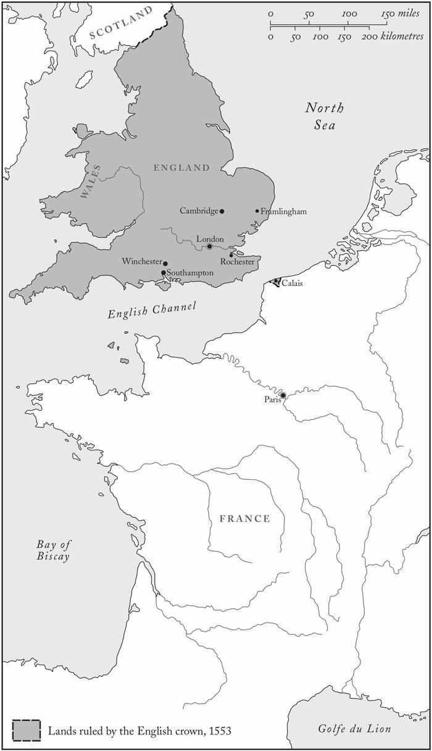

In 1553, just as in 1547, the councillors were the strategic architects of the change of regime. The difference now was that the new monarch was their puppet not because he was a child, but because she was a woman: Jane Grey, the chosen vessel through whom Edward’s plan for a legitimate, Protestant and male succession would ultimately be achieved, and through whom the duke of Northumberland’s control of government would meanwhile be upheld. On Sunday 9 July, with the cordon of secrecy still in place around the dead king’s darkened chamber at Greenwich, Jane received an enigmatic summons to Syon House, Northumberland’s lavish home ten miles west of the capital, ‘to receive that which had been ordered by the king’. On her arrival the bewildered girl was met by the duke and other members of the Privy Council who knelt before her, offering their allegiance and their service to the new queen of England.

The next day, brightly dressed heralds at last appeared on London’s streets to inform Edward’s subjects that their king was dead and to proclaim the accession of Queen Jane. As they did so, a flotilla of barges carried the young queen and her hastily assembled royal entourage downriver to the Tower, where she made a ceremonial entry into the monarch’s apartments. England’s new ruler was a short and slender fifteen-year-old, with auburn hair and freckles powdering her pale complexion, but on this summer afternoon her slight frame was overwhelmed by the trappings of her royal destiny – a heavy gown of green velvet embroidered with gold, a white headdress weighted with jewels, and cumbersome wooden platforms strapped onto her small feet to make her more easily visible to her new subjects.

So began the reign of Queen Jane. Already, however, there were signs that this female repository of royal power might be less passively accommodating than Northumberland had hoped. Jane’s discomfort with her new role was more than superficial. She was sharply intelligent and stubbornly principled, and if the duke had assumed that she would be a malleable tool of her cousin’s design for the succession, he had begun to be disabused of that presumption from the moment the plan was put into action. At Syon the previous day, her first reaction to the news of Edward’s death and her own elevation to his throne had been a storm of grief for her cousin; her second was horror. ‘The crown is not my right and pleases me not,’ one of the councillors reported her saying. ‘The Lady Mary’ – the elder of Edward’s two sisters – ‘is the rightful heir.’ It took all the pressure that Northumberland, her parents and her new husband, the duke’s son Guildford, could muster before she was induced to accept her accession as the will of her Protestant God.

But acquiescence in this did not mean acquiescence in everything. The royal treasures held in the Tower included the crown itself, which the Lord Treasurer attempted to persuade her to try on, saying as he did so, Jane later recounted, that ‘another also should be made, to crown my husband’. The status of a reigning queen’s

husband was an issue without precedent in England, but special envoys sent by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, for example, took it for granted that the accession of Queen Jane Grey meant the simultaneous elevation of King Guildford Dudley. (‘The new king and queen are to be proclaimed this very day,’ they reported on 10 July, before seeking advice from their imperial master about what they should do if they were offered an audience by the council and ‘the new king’.) Jane, however, had other ideas. She had been prevailed upon to accept, reluctantly, that the crown might be hers, but she was certain that it was not her husband’s. She would make him a duke, she told her councillors, but not king – a stand which precipitated a furious row with the duke and duchess of Northumberland and with eighteen-year-old Guildford himself, who persisted in conducting himself with elaborate ceremonial of a kind that suggested he too was England’s monarch.

Northumberland had expected a puppet, and was finding instead that Jane was prepared to flex her royal muscles. Jane herself, meanwhile, was wrestling (she later wrote) with ‘a troubled mind … infinite grief and displeasure of heart’, as she struggled to cope with the shock of a situation in which her father-in-law, her parents and her husband were foisting royal power upon her, and simultaneously seeking to prevent her from exercising it. Clearly, there were battles ahead. For the moment, however, they would have to wait, overtaken as they rapidly were by battles at hand, since the implementation of Edward’s ‘device for the succession’ was not proceeding as smoothly as it might have seemed from within the Tower’s royal apartments.

The first indication that all was not well was the silence on London’s streets when Jane’s queenship was declared. No bells were rung, no bonfires lit, no caps flung into the air. Instead, the news was met with a mixture of puzzlement and resentment under a muffling blanket of fear. The proclamation read out by the heralds that day had detained its listeners for an unusually long time, in part because of the need to explain exactly who the new queen was. If the idea that she might inherit the throne had come

as a shock to Jane herself, it was a bolt from the blue for the people who were now required to accept her as their monarch. The Emperor Charles V had to ask his envoys to compile a family tree to explain the merits or otherwise of Jane’s claim; how much more at sea were her new subjects as they watched their young queen enter the Tower, her long train carried, confusingly, by the mother through whom her right to the crown was said to have come.

Puzzlement, then, at who Jane was, and resentment at who she was not – this being the second issue on which the heralds found themselves expounding at length. The circumstances which had persuaded Edward of her virtues as a candidate for his throne had much less purchase on the hearts and minds of his subjects. Jane’s commitment to the evangelical faith which Edward was so desperate to see nurtured and protected in his realm could not be doubted, but few of England’s people were as deeply convinced as their king of the doctrinal reformation over which he had presided, and in England’s parishes there remained much support still for the old ways of prayer and worship that had been so suddenly prohibited. Not many were prepared to emulate the rebels who had taken up arms for their beliefs in the west country in 1549, but few would see the reformed religion as reason enough to overturn the legitimate line of the royal succession.