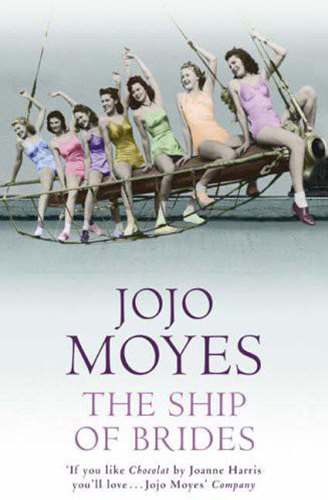

Ship of Brides

Authors: Jojo Moyes

CONTENTS

THE

SHIP OF BRIDES

Jojo Moyes

Also by Jojo Moyes

Sheltering Rain

Foreign Fruit

The Peacock Emporium

Copyright © 2005 by Jojo Moyes

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Hodder and Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK Company

The right of Jojo Moyes to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978 1 84894 747 4

Book ISBN 978 0 340 96038 7

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

An Hachette Livre UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NWl 3BH

To Betty McKee and Jo Staunton-Lambert,

for their bravery on very different journeys.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book was a huge undertaking in terms of research, and would not have been possible without the generous help and time given by a large number of people. First thanks must go to Lt Simon Jones, for his good-humoured and endlessly patient advice regarding the finer details of life on board an aircraft carrier – and for particularly imaginative advice on how I could set my ship alight. Thanks, Si. Any mistakes are purely my own.

Thanks more widely to the Royal Navy, particularly Lt Commander Ian McQueen, Lt Andrew G. Linsley, and all those on board HMS

Invincible

for allowing me to spend time on board.

I’m very grateful to Neil McCart of Fan Publications for allowing me to reproduce extracts from his excellent and informative book HMS

Victorious

. And to Liam Halligan of Channel 4 News, for alerting me to Lindsay Taylor’s magnificent piece of film:

Death at Gadani: The Wrecking of

Canberra.

Access to unpublished journals kept during this time has been fascinating and helped add colour to a period I was born too late to experience. Thanks in this case to Margaret Stamper, for allowing me to read her husband’s wonderful journal of life at sea, and reproduce a little of it, and to Peter R. Lowery for allowing me to do the same with that of his father, naval architect Richard Lowery. Thanks also to Christopher Hunt and the other staff of the Reading Room at the Imperial War Museum, and those at the British Newspaper Library in Colindale.

Miscellaneous thanks, in no particular order, to Mum and Dad, to Sandy (Brian Sanders) for his marine knowledge and huge library of naval warfare books, Ann Miller at Arts Decoratifs, Cathy Runciman, Ruth Runciman, Julia Carmichael and the staff at Harts in Saffron Walden. Thanks to Carolyn Mays, Alex Bonham, Emma Longhurst, Hazel Orme and everyone else at Hodder and Stoughton for their continuing hard work and support. Thanks also to Sheila Crowley and Linda Shaughnessy at AP Watt.

And thanks to Charles, as ever, for love, editorial guidance, technical support, babysitting and for managing to look interested every time I told him some fascinating new fact about aircraft carriers.

But greatest love and thanks to my grandmother, Betty McKee, who, nearly sixty years ago, made this very journey with unimaginable faith and courage, and still remembered enough about it to give me the basis of this story. I hope Grandpa would have been proud.

Extract from the poem ‘The Alphabet’ by war bride Ida Faulkner quoted in

Forces Sweethearts

by Joanna Lumley reproduced with kind permission of Bloomsbury publishers and the Imperial War Museum.

Extract from

Arctic Convoys 1941–45

by Richard Woodman reproduced with kind permission of John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.

Extracts from the

Sydney Morning Herald

, the

Daily Mail

and

Daily Mirror

are included with the kind permission of the respective newspaper groups.

Extracts from the papers of Avice R. Wilson reproduced with the kind permission of her estate holders and the Imperial War Museum.

Extracts have also been included from

Wine, Women and War

by L. Troman, published by Regency Press;

A Special Kind of Service

, by Joan Crouch, published by Alternative Publishing Cooperative Ltd (APCOL) Australia; also extracts from

The

Bulletin

(Australia) and the

Truth

(Australia): all efforts have been made to contact the rights holders but without success. Hodder and Stoughton and the author will be happy to acknowledge all extracts if they care to get in contact.

In 1946 the Royal Navy entered the last stage of its post-war transport of war brides, those women and girls who had married British servicemen serving abroad. Most were transported on troopships, or specially commissioned liners. But on 2 July 1946 some 655 Australian war brides embarked on a unique voyage: they were sailing to meet their British husbands on HMS

Victorious

– an aircraft carrier.

More than 1100 men – and nineteen aircraft – accompanied them, on a trip that lasted almost six weeks. The youngest bride was fifteen. At least one was widowed before she reached her destination. My grandmother, Betty McKee, was one of those lucky enough to have her faith rewarded.

This fictional account, inspired by that journey, is dedicated to her, and to all those brides brave enough to trust in an unknown future on the other side of the world.

Jojo Moyes

July 2004

NB All extracts are non-fictional and refer to the experiences of war brides, or those who served on the

Victorious

.

PROLOGUE

The first time I saw her again, I felt as if I’d been hit.

I have heard that said a thousand times, but I had never until then understood its true meaning: there was a delay, in which my memory took time to connect with what my eyes were seeing, and then a physical shock that went straight through me, as if I had taken some great blow. I am not a fanciful person. I don’t dress up my words. But I can say truthfully that it left me winded.

I hadn’t expected ever to see her again. Not in a place like that. I had long since buried her in some mental bottom drawer. Not just her physically, but everything she had meant to me. Everything she had forced me to go through. Because I hadn’t understood what she had done until time – aeons – had passed. That, in myriad ways, she had been both the best and the worst thing that had ever happened to me.

But it wasn’t just the shock of her physical presence. There was grief too. I suppose in my memory she existed only as she had then, all those years ago. Seeing her as she was now, surrounded by all those people, looking somehow so aged, so diminished . . . all I could think was that it was the wrong place for her. I grieved for what had once been so beautiful, magnificent, even, reduced to . . .

I don’t know. Perhaps that’s not quite fair. None of us lasts for ever, do we? If I’m honest, seeing her like that was an unwelcome reminder of my own mortality. Of what I had been. Of what we all must become.

Whatever it was, there, in a place I had never been before, in a place I had no reason to be, I had found her again. Or perhaps she had found me.

I suppose I hadn’t believed in Fate until that point. But it’s hard not to, when you think how far we had both come.

Hard not to when you think that there was no way, across miles, continents, vast oceans, we were meant to see each other again.

India, 2002

She had woken to the sound of bickering. Yapping, irregular, explosive, like the sound a small dog makes when it is yet to discover where the trouble is. The old woman lifted her head away from the window, rubbing the back of her neck where the air-conditioning had cast the chill deep into her bones, and tried to straighten up. In those first few blurred moments of wakefulness she was not sure where, or even who, she was. She made out a lilting harmony of voices, then gradually the words became distinct, hauling her in stages from dreamless sleep to the present.

‘I’m not saying I didn’t like the palaces. Or the temples. I’m just saying I’ve spent two weeks here and I don’t feel I got close to the real India.’

‘What do you think I am? Virtual Sanjay?’ From the front seat, his voice was gently mocking.

‘You know what I mean.’

‘I am Indian. Ram here is Indian. Just because I spend half my life in England does not make me less Indian.’

‘Oh, come on, Jay, you’re hardly typical.’

‘Typical of what?’

‘I don’t know. Of most of the people who live here.’

The young man shook his head dismissively. ‘You want to be a poverty tourist.’

‘That’s not it.’

‘You want to be able to go home and tell your friends about the terrible things you’ve seen. How they have no idea of the suffering. And all we have given you is Coca-Cola and air-conditioning.’

There was laughter. The old woman squinted at her watch. It was almost half past eleven: she had been asleep almost an hour.

Her granddaughter, beside her, was leaning forward between the two front seats. ‘Look, I just want to see something that tells me how people really live. I mean, all the tour guides want to show you are princely abodes or shopping malls.’

‘So you want slums.’

From the driver’s seat Mr Vaghela’s voice: ‘I can take you to my home, Miss Jennifer. Now this is slum conditions.’

When the two young people ignored him, he raised his voice: ‘Look closely at Mr Ram B. Vaghela here and you will also find the poor, the downtrodden and the dispossessed.’ He shrugged. ‘You know, it is a wonder to me how I have survived this many years.’

‘We, too, wonder almost daily,’ Sanjay said.

The old woman pushed herself fully upright, catching sight of herself in the rear-view mirror. Her hair had flattened on one side of her head, and her collar had left a deep red indent in her pale skin.

Jennifer glanced behind her. ‘You all right, Gran?’ Her jeans had ridden a little down her hip, revealing a small tattoo.

‘Fine, dear.’ Had Jennifer told her she’d got a tattoo? She smoothed her hair, unable to remember. ‘I’m terribly sorry. I must have nodded off.’

‘Nothing to apologise for,’ said Mr Vaghela. ‘We mature citizens should be allowed to rest when we need to.’