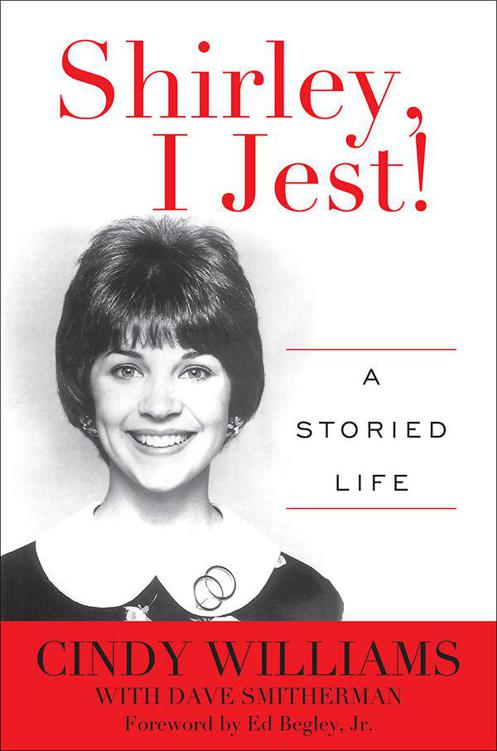

Shirley, I Jest!: A Storied Life

Read Shirley, I Jest!: A Storied Life Online

Authors: Cindy Williams

Shirley,

I

Jest!

Shirley,

I

Jest!

A Storied Life

Cindy Williams

with Dave Smitherman

Taylor Trade Publishing

Lanham • Boulder • New York • London

Use of photos from

Laverne & Shirley

—Courtesy of CBS Television Studios

Published by Taylor Trade Publishing

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright © 2015 by Cindy Williams

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Williams, Cindy, 1947 August 22-

Shirley, I Jest! : a storied life / Cindy Williams.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-63076-012-0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-63076-013-7 (electronic)

1. Williams, Cindy, 1947 August 22- 2. Actors—United States—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.W465A3 2015

791.4302’8092—dc23

[B] 2014042840

™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

I dedicate this book not only to my treasure of family and friends, but also to all the animals I have had the privilege to know and love. Thank you all for your encouragement and unconditional love.

And this goes for Boo Boo Kitty too!

jest

(jest)

n

. 1. To act or speak in a playful manner

Contents

Chapter 2: Love, Peace, and Happiness

Chapter 5: Some Enchanted Evening

Foreword

Ed Begley Jr.

America fell in love with Cindy Williams in 1977, when she began her hit show

Laverne & Shirley

. But, I fell in love with her seven years prior to that, at the wrap party for

Room 222

.

Though ours was never the romantic relationship I had hoped for after that first meeting, it wasn’t for lack of trying. Our first date consisted of me picking her up in a three-wheel 1970 electric vehicle, which was not exactly a babe magnet. It was so slow that a kid on a scooter passed us by and gave us the finger. I decided to bide my time and wait for the right moment to pounce on her, but that didn’t work out so well either.

I lulled her into a false sense of security, and convinced her to spend a weekend with me at Two Bunch Palms. After two years of waiting, I had little pride remaining. I did what any red-blooded male would do under those conditions. I begged her to let me into her room in hopes of getting to first base. I tried her door. Locked! And she probably had it bolted from inside. I thought about going around back to “jimmy” the window, but then the police might get involved. No, I had to make my peace with it. I had long ago become like a brother to her, and after weeping and begging, I quickly surmised that being her “brother” was a pretty sweet deal.

Her generosity in my life was endless. She became one of the biggest champions of my work as an actor, a stand-up comic, and an environmentalist. She loaned me a huge sum of money so I could buy my first house. She introduced me to a holistic doctor who kept me healthy for decades. She became the godmother to my daughter, Amanda. She got me cast as her brother on

Laverne & Shirley

. She introduced me to a long list of brilliant and creative people that are still an important part of my life.

We saved trees together, went on trips together, broke down on the highway together, and had many fantastic adventures together.

Though it wasn’t what I had in mind at first, being considered “family” by this talented and dynamic woman is simply wonderful.

I suppose I should pay her back the money I borrowed.

Photo by Tricia Lee Pascoe

One

Valley Texas Gal

I gingerly opened the door to the smoke-filled Green Room at the Pasadena Playhouse and immediately started coughing. Everyone seemed to have a lit cigarette except for Betty Garrett and Cyd Charisse, who were sitting on a couch, chatting. I caught a glimpse of Frank Sinatra and Liza Minnelli sharing a laugh. Lucille Ball and her husband, Gary Morton, were playing mah-jongg. I made a hasty retreat, shutting the door quickly, hoping no one saw me. My coughing subsided, but now my head was spinning. How could they be so calm, carefree, and collected while I was having a full-blown anxiety attack? It was 1978;

Laverne & Shirley

was a huge success and I should have had the confidence of a gladiator. The corridor seemed to be swaying back and forth. Afraid I was going to faint, I leaned against the wall for support and dropped like a bag of bricks straight to the floor! I had leaned into a clothing rack by mistake. How had I gotten myself into this? In less than an hour I would step out onto the stage at the Pasadena Playhouse and sing “You Wonderful You” from the movie

Summer Stock

as a duet with Gene Kelly. My mouth was dry. How would I ever be able to sing, let alone on key? My heart was pounding like a sledgehammer.

Even as a little girl I suffered from anxiety. My mother was always telling me to stop biting my nails, or commenting on how I could never sit still. In school I was punished for not being able to keep quiet. One time in second grade, I had to sit on a stool in the corner with a dunce cap on my head for talking too much and too loud. I was also painfully shy, which seems contradictory, but it’s true. As much as I wanted to socialize and be a leader, a part of me resisted. Still, there was another ever-present part of me that longed to express the fantastic things I was imagining, share the fun of my shadow world—loudly and with exuberance. This is what earned me the dunce cap.

I started life in Van Nuys, California, in the San Fernando Valley. I’m what you might call a “Valley Girl.” When I was born I had rickets; a vitamin D deficiency that affects the bones. My mother, Frances, loved to tell the story as though it were the Holy Grail of medical riddles. She would say,

Rickets, of all things. Your little legs were bowed and I had to give you goat’s milk, because you couldn’t tolerate cow’s milk. You also had the colic, poor little thing . . . crying and throwing up all the time. I labored for thirty-six hours. They finally knocked me out with ether, and then used the forceps on you.

(I have always blamed this use of forceps at my birth for my egg-shaped head!) My mother vigilantly researched this condition and eventually got me over it. And as a result, she started taking an avid interest in health and preventative medicine, ultimately becoming a lifelong devotee of Jack LaLanne and other health gurus. She collected tomes on the subject of wellness, and if anyone around her had a health complaint, she would check their tongue and skin coloring and then look it up. She became excellent at diagnosing and suggesting remedies for any maladies that crossed her path. Frances was ahead of her time.

My father’s name was Beachard Williams, but he liked to be called Bill; which was odd because that was his brother’s name. His family was from Texas and Louisiana. Their origins were Welsh, French, and Cherokee. My father was the kindest man I’ve ever known—fun-loving and affable—until he was drinking. When he drank he became the devil, and a very dangerous character to deal with. When I was a year old my mother left my father because of his drinking and aggressive behavior. We took the train to live with my grandmother Anna in Dallas, Texas, where my mother and father had met years before.

My grandmother was Sicilian and had emigrated with her younger brother Joe from “The Old Country” to America by way of Ellis Island and into Manhattan where my mother and her brother, Sam, were born. My grandfather had died falling off a truck on the way home from a winning streak in a poker game. My grandmother swore he had been pushed. Murdered by the Black Hand. When my mother was seven, my grandmother moved her family from Manhattan to Dallas, Texas, where her brother Joe had gone to live earlier.

After a year of living peacefully with my grandmother, my father showed up, and begged my mother to get back together. She agreed and the next year my sister, Carol, was born and we all lived together with my grandmother in her house on Poplar Street.

My brother, Jimmy, is seventeen years older than me. He is my mother’s son from her first marriage and had already fled to our grandmother’s house in Dallas to escape the drunken abuse my father would sometimes direct his way. When Jimmy was eighteen, he joined the Air Force and was out of the house for good.

Everyone worked during the day. My mother waitressed at a high-end restaurant in downtown Dallas called Town and Country. My father climbed telephone poles and repaired cables for the city. My grandmother worked at a men’s tailor shop making buttonholes. During the day my sister was always left down the street with a babysitter, while I remained home with the elderly lady who rented the front bedroom from my grandmother. I called her Mama Helen. She was in her late seventies, slightly handicapped, and needed help to get around. At age four, this became

my

job. I was basically an underage home health aide. Mama Helen taught me how to play Solitaire and we would pass the day while playing cards and listening to soap operas on the radio—

The

Guiding Light

,

Romance of Helen Trent

,

and, of course,

Young Dr. Malone

. How Mama Helen got to Texas was a mystery to me, but I knew she came from Pennsylvania and other than us had no family.

My mother worked a split shift and sometimes would come home during her break to put me down for a nap. I could never sleep, never nap—the thought of her leaving again for her shift and not returning until late was too dreadful. I knew my father would be home before her, and he’d be drinking. I would be in for a night of hearing him rant at my poor grandmother who he was thoroughly contemptuous of, mostly because she was Italian and spoke only broken English. Although this turmoil caused by my father frightened me, I would still be comforted to see my grandmother round the corner, walking toward home from the bus stop after work.

My grandmother kept a chicken coop in the backyard. Many evenings after work she would go out there, grab a chicken and with an axe, expertly dispatch its little chicken soul off to heaven. This was disturbing to me as a small child; I felt sorry for the chicken. But I was torn because my grandmother was an excellent cook! Sometimes my job was to feed the chickens. Many of them were vicious and would try to attack me, especially the rooster who would peck at my legs as I ran for the gate. I felt that the chickens knew their ultimate fate. They would tell me this with their chicken eyes! Chickens are not dumb. A lot of the time I would open the gate, throw all the chicken feed in at once and shut it before the rooster got ahold of me. I suppose he was just doing his job, too. When I was seven, my grandmother made me a sweet little dress out of a chicken feed sack and I loved it.

In 1951, when I was still four, my grandmother made a purchase that would change my life. She bought a small black-and-white television set. I remember it being delivered and perched on top of a table next to the radio. From that moment on, Mama Helen and I watched anything and everything:

Ding Dong School

,

Search for Tomorrow

,

Arthur Godfrey Time

. I loved it all! Even the Lucky Strike cigarette commercials. I would mimic, memorize, and reenact. I was swept away into this brand-new world. In the evenings my grandmother and I would watch wrestling together. She was in love with Gorgeous George! Me, not so much, but I was mesmerized by the

golden

bobby pins he would toss out ceremoniously to his adoring fans.

When my father was sober, he too loved watching TV. He would sometimes call out to me saying, “Come in here, Cindy, you’re going to like this.” It was always something great like

Your Show of Shows

,

The Milton Berle Show

,

Jackie Gleason

. When he was sober, he was so much fun. We would laugh out loud at the same things at the same time. When he was sober he was a good father. When he was sober.

I was six when we moved to a small house in Irving, a town about thirteen miles northwest of Dallas. My father bought the house with an acre and a half of land so he could raise pigs and chickens, and harvest the pecans from the huge tree that sat on the property. At that time, Irving was extremely rural, with lots of dirt roads, empty fields, and pastures. I played barefoot and wandered for miles up and down the creek bed alone. I had no fear of the crawdads that nipped at my toes, the spiders and bugs, or the occasional snake crossing the road as the sun went down.

In Texas in those days, kindergarten didn’t exist. You started the first grade at the age of six. In September 1953 my mother took me for my first day of school at East Elementary in Irving, Texas. I clung to her and began crying when she tried to leave me. She did her best to reassure me, which made me cling even harder. Mrs. Smith, my teacher, attempted to soothe me, telling me that my mother would be back to pick me up. I knew this wasn’t true. She would be working. After she left, I wouldn’t see her until the next morning. It was my father who would pick me up and he would most likely be drinking—a secret I could not share with my mother and certainly not with Mrs. Smith.

We were standing on the school playground. My mother pointed out the large slide, and asked me if I wanted to climb up and slide down. I did! I had never been on a slide that high. She took me over and stood at the foot of it, ready to catch me as I flew down to the bottom. I loved it! I climbed back up and slid down two more times with my mother catching me. Holding me, she asked if I would be all right now. I said I would if I could keep playing on the slide. Mrs. Smith said, “Yes,” for as long as I liked. My mother left and I kept sliding, exhilarated by the speed, forgetting for a while my mother’s absence.

My mother had a strict rule about the clothes she bought me and my sister, Carol. No matter what the article of clothing was, it had to be purchased two sizes larger than necessary. This was so we could “grow into them.” Oh, and no white clothes,

never

any white clothes. They would only “show the dirt.”

By third grade I was either walking home or taking the school bus. The bus driver had a fun rule. The first kid on the bus got to stand by the driver and operate the handle for the door, opening and closing it for each student getting off. Every kid vied for this job, including me. One winter day it was mine! Climbing on the bus first, the bus driver smiled and gestured for me to stand beside him and be the “keeper of the handle.” There was one little problem; the brown winter coat my mother bought me was her required two sizes too big. The sleeves hung down, covering my hands like oven mitts. I tried to roll them up, at least to uncover one hand to maneuver the handle. Kids streamed past me to take their seats for the ride home while I struggled with my coat sleeve. When the bus driver was ready to take off, he looked at me and asked, “Ready?”

I had not been able to roll the coat sleeve up far enough so I used it as a glove over the handle and managed to close the door. The driver couldn’t help himself; his smile turned into a laugh. I turned around to face the student passengers, who also began to laugh. It was then I got the full measure of what I must look like; sleeves hanging down to my knees; coat to the ground. My mother had purchased a real clown suit! Her system of planning for the future was not working out well for me. I didn’t cry. I was, however, humiliated. I looked at the driver and told him I no longer wanted to be the keeper of the handle, and took the closest seat I could find. Like a vampire when the sun goes down, some ambitious kid jumped up and claimed my job. I had no way of knowing at that moment that my mother’s practicality would one day work in my favor as I would remember and use this frugal sense of fashion as the basis for the wardrobe of Shirley Wilhelmina Feeney.

My mother was still working at Town and Country and was always gone. She convinced my father that my two-year-old sister should stay with my grandmother in Dallas, leaving me alone when I got home from school. My mother had instructed me to always stay in the house until Daddy got home. And if a tornado was threatening the area, she told me to run to the neighbor’s house for shelter in their basement. What my mother didn’t know was that if I heard my father’s truck pulling up to the house two minutes late, it would mean that he had stopped off for a bottle of Thunderbird. It would also mean that I would likely be spending the night sitting in the locked cab of his truck, parked outside a bar watching a neon Schlitz or Pabst sign blink on and off. I’d sit there waiting for him to stop drinking in the hopes that we would get home in one piece before my mother returned at 11:30 p.m. My father warned me never to tell her.

I always prayed we’d get home without getting into an accident. I would never sleep until my mother came in. I couldn’t. I would lay in bed, listening to my father stumbling around in the living room, hoping he wouldn’t pass out and start a fire with one of his ever-burning cigarettes. The relief I would feel when my mother finally appeared in my bedroom was euphoric. I could smell the wonderful aroma of fancy restaurant food mixed with her perfume as she bent over to straighten my covers and kiss me goodnight. I would pretend to be asleep, the night out with my father a frightening secret I would keep. These nights continued with my mother being none the wiser. We would sometimes take off and travel as far as Lubbock, so he could drink with his cousins and crazy Aunt Rennie. She would sit me down in the kitchen and preach hellfire and damnation with an ever-present drunken slur. When her sermon was finished, I would be rewarded for my attention with a piece of peanut butter pie. On our ride home every night from wherever our drunken adventures had taken us, if I spoke it would be in soft, quiet tones trying to keep his rage at bay so we could make it back to the house in one piece. Because of these nights of distraction I did not do well in school. I was always sleepy and couldn’t concentrate.