Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (32 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

Our location was the mountain of Metéora, which would be difficult to climb, the slippery surface making it impossible even for James Bond. At its peak was a monastery housing the monks, isolated from the outside world, with all their needs or anything else the religious order required pulled to the top in a basket, keeping them safely inaccessible in their sanctuary. The gossip from our curious locals was of young boys who occasionally made trips up in the basket, though of more concern to the production were the monks’ attempts to disrupt our filming by hanging out their washing and making loud noises. In the end we got most of what we needed, with a few additional sequences being filmed once we were back at Pinewood.

Some of the cleverer sequences we filmed in the studio involved matching our dry-for-wet shots with the wider angle sequences that had been filmed by the underwater unit in the Bahamas. Underwater filming is difficult enough at the best of times and can only be carried out by properly qualified technicians, but some of Alan’s supposedly ‘underwater’ sequences with the principal actors were little short of miraculous. On a stage it was simple enough to film close ups on the principal actors’ faces, filming at high speed through a water tank (with the occasional air bubbles for added effect) while a hidden fan blew through the actors’ hair. The effect was totally convincing – another simple camera technique seemingly forgotten in this CGI age.

The tried-and-tested Bond formula would continue to please, with the customary beautiful girls, the latest gadgets for 007’s teasing of Q and Miss Moneypenny’s eternal flirting with James. This time, however, M would be conspicuous by his absence, with Bernard Lee having died in January 1981 before we were scheduled to film his scenes at Pinewood. Rather than re-cast the part the producers felt that it would be more appropriate for the rewritten script to have M on sabbatical with the distraught Minister of Defence played by Geoffrey Keen, whose hair seemed to get greyer with every 007 assignment, filling in. Topol now joined the cast as Bond’s unlikely ally with Julian Glover as a convincing baddie, while Carole Bouquet would take the lead female role with the very pretty professional ice-skating champion Lynn-Holly Johnson adding to the interest.

Alan Hume had now reached the peak of his career so it would not be a surprise to learn that his next film had already been arranged with director Richard Marquand, with whom we had previously worked on

Eye of the Needle

. Alan would be the cinematographer on what at the time was supposed to be the final episode in George Lucas’s

Star Wars

film series, with me tagging along…

Whatever occupation we follow as a career, either by choice or opportunity, our lives become routine, at times making it difficult to understand others with their unseen problems. The film industry is no different; in our work we meet many interesting people, actors and technicians alike, who possibly have different opinions to our own.

On the other hand, others have temperaments which need to be handled more carefully otherwise you could never be sure of the final outcome. Some remain biased with their own opinions and make it clear that there can be no further discussion on the matter, which usually fits their character. We all recognise these sad people with their depressing attitude to life, but that is their problem so we get on with the job. As human beings we have the right to different opinions which others may find difficult to accept and certainly not easy to write about. Even so, one’s honesty remains, whatever the outcome; but ‘if the face doesn’t fit’ is a problem which we all experience from time to time – we might need to handle a situation more carefully.

‘Revenge of the Jedi’ was the original title on the script, although this would change before filming began at Elstree Studios, the English home of the

Star Wars

movies at the time. This decision came from the producer George Lucas, who decided that the word ‘revenge’ was not a Jedi concept and would send the wrong message to young people.

Return

of

the

Jedi

was to be the last instalment of the original trilogy created by George Lucas, with Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher continuing in their established roles, as would Alec Guinness as Ben ‘Obi-Wan’ Kenobi.

Having enjoyed the two previous

Star Wars

films I looked forward to working on this final episode, and to be part of the experience. Episode VI (the prequel trilogy had yet to be made) had a fun atmosphere on the set, where the randy dwarfs competed for individual stardom. Although I use the word ‘randy’ with tongue in cheek, this observation comes from their adventurous ways; should an attractive lady pass through the stage she would quickly draw the magnetic attention of our small friends, their stature not holding them back!

This lively feeling on set every day is how I would prefer to remember my time on

Return of the Jedi

, with enjoyment had by all and a daily routine which would make my Ewok experience one to remember; in the end, though, I would be left with a feeling of bitterness and resentment due to the behaviour of a fellow human being.

Return of the Jedi

was the last film in the series and would finally expose the face behind the mask of Darth Vader, the villain, who was finally unmasked by his son, Luke Skywalker. Secrecy surrounded the production to such an extent that few people had a complete script, and even those complete scripts were carefully numbered to avoid them being copied and passed on to the press – my number was 021. However, another dark mask was hiding in the shadows, where possibly the original title word ‘revenge’ would be more appropriate. I would now learn the hard lesson of when or when not to have an opinion which differed to those in higher authority – let alone expressing it!

Filming had barely started in January 1982 when the nameless one decided that he had seen something in the rushes that he did not like. I should explain that his concern had nothing to do with my work – that I clearly remember. What I also remember is that his comment was not particularly important; as the Americans say, ‘hardly a big deal’! To be fair to the gentleman, though, it was his right to have an opinion and to express it, but it was also my right to disagree with his point of view, which I did, politely – a big mistake! Perhaps it was because camera operators only operate the camera in America, leaving the cinematographer to discuss the rushes with the director, but here in the UK the director and camera operator probably work far more closely together. If this were not the case then I would have been guilty of breaking the so-called unwritten rule of minding your own bloody business, Alec!

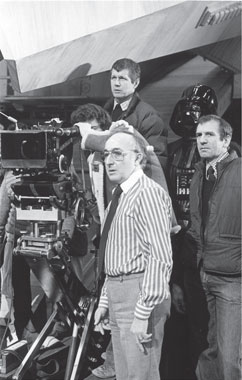

With Richard Marquand, George Lucas (looking through the camera) and Mike Frift (focus puller) at Elstree Studios on

Return of the Jedi

(1980), with an evil Sith Lord peering over my shoulder. He wasn’t the only one … (© & ™ Lucasfilm Ltd. All rights reserved. Used under authorisation)

Later on, George Lucas came in to see the rushes with the director; after the screening both were happy with everything they had seen on the screen with no further comment about the concerns of the other person. You would have thought that this would have been it, but sadly this was not the end of the story. After that the nameless one would not speak to me again throughout our filming in the studio, preferring instead to look the other way and totally ignore me. In hindsight this should have been a clue as to what would come.

With our filming going well and the constant banter on the set, the unit began to think about flying on to America for the six weeks of location filming at Yuma in Arizona, followed by Crescent City in California. It was at this point that strange things started to happen which gave me reason for concern, though somehow I could not put my finger on the problem. Even so, something was definitely wrong and there was a sudden change in attitude directed towards me personally, particularly from the production office, which was surprising since we had had no problems with communication regarding my work in the studio. My suspicion that something was wrong would be confirmed when the production manager, with whom I had worked in the past and enjoyed a good relationship, was noticeably avoiding eye contact with me, sometimes turning to look the other way. Strange … this was not the friendly colleague I knew and respected, so obviously something was wrong. I mentioned this to Alan, who thought it was just my imagination, even so the concerns persisted and refused to go away. I would soon be proved right.

To bring this sad account to a close, all I wanted was for someone to give me an honest explanation as to why the camera operator on the film was the only member of the camera crew not to go to the USA, which could only leave me with the inescapable conclusion that a real-life Darth Vader here on planet Earth was seeking his revenge on me, now sadly leaving me with a legacy of bitterness towards this wonderful Jedi experience. What irritates me to this day, even in retirement, is how an adult can be so immature in turning a nothing issue into a personal vendetta for no real reason at all. I can only think that this gentleman was hurt by my honest comment – a sad creature, to be sure – though no doubt we all meet up with this sort of person at certain times in our lives.

If my comments appear sour, let me emphasise that I really enjoyed working on

Jedi

; everything about the experience was truly amazing, apart from my one moment of apparent madness when it seems that I had the audacity to politely disagree with a man in high office. However, I must also be completely honest with all that happened and say that to my knowledge no one spoke up to challenge this childish decision that the camera operator would not go to America; others would need to live with that judgement. Am I bitter after all this time? You bet I am!

Recently I read somewhere online that Alan also had a falling out with the same person with whom I had the problem, which was apparently due to the poor treatment of the director Richard Marquand; after that Alan was allegedly transferred to another unit while Alec Mills took over as cinematographer. I do not know where this came from but obviously it was untrue as that idiot had got rid of me earlier on. The film business is a tough world to survive in.

There would be one more interesting postscript to this account, which was not surprising. I would later be told that the same person had been given ‘other responsibilities’ on the film, possibly due to the harm he caused Alan, though I doubt he would have any conscience about all the damage he created for us both.

Thinking later about this unpleasant incident I was reminded of my dad, who ‘impolitely’ dared to share his opinion with an army officer about his mistreatment of a horse on the Western Front. It would seem that we definitely share the same DNA so I will now dry my eyes and make an effort to put this sad experience behind me …

On the other hand, something positive would come from all this foolishness. Now more than ever I felt this would be the time to move up the ladder and start thinking in terms of lighting, come what may. Politics such as this finally forced me to take the decision which I should have made earlier, and underlined the direction in which my future really lay.

On his return to the UK Alan offered me his next film,

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

. Although still smarting from the injustice of the

Jedi

experience, I decided not to bring the issue up and let sleeping dogs lie. What would be the point now, anyway?