Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (41 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

One of the more cultural locations used was Ernest Hemingway’s old home in Key West, where M, played for the last time by Robert Brown, ‘revokes’ 007’s licence to kill. I use that word as the original production title had been ‘Licence Revoked’, but due to American understandings of the word the title was eventually changed to

Licence to Kill

– another case of our two countries divided by a common language! As a result, Bond finds himself out on his own, determined to take revenge on the villain, played by Robert Davi, responsible for crippling his long-time friend and colleague Felix Leiter, played by David Hedison. Perhaps the most interesting location was at the Otomi Cultural Center at Temoaya, an amazing structure which could have been specially built for a Bond movie.

For its sheer mystery – if you believe in this sort of thing – special mention should made of the location near the town of La Rumorosa, where Arthur Wooster’s second unit filmed parts of the climactic tanker chase sequence. Located near Mexicali on the American–Mexican border, a number of unexplained incidents took place. The road was already known to be dangerous due to the sharp bends and sheer drops. While you are always prepared for the occasional accident while filming stunts and action sequences, too many mishaps and strange occurrences – including spectral figures beside the vehicle compound at night – seemed to be happening to be called just coincidence. Added to that, no one could explain one image taken by the second-unit stills photographer George Whitear, of an explosion with what looked like skulls and faces in the flames, and the flaming fingers of what appeared to be an arm shooting down over a precipice. To add to this, a Mexican policeman later said that the explosion had been filmed on the exact spot where several nuns had been killed in a road accident a few years before.

All of the images for the film were achieved by separate units spread across the country, with Mexican camera crews working alongside the Brits on both the first and second units and the miracle of John Grover’s slick editing once again ensuring that everything came together to complete the illusion. As ever, the film unit observed the life of both the rich and poor, and, while it was only a film to us, you were always aware of the government officer assigned to keep an eye on us. However, one thing is undeniable; through my twenty years of service with 007 I would experience the taste of a privileged life, mixing with the famous and visiting some of the most beautiful places one could possibly imagine. To balance this, I would also never forget some of the poverty-stricken locations visited with our filming, where the poorest struggled to survive and where strangers with cameras are looked on with great suspicion.

We finally completed filming in Mexico City in November 1988. At the time there was little to suggest that this would by my last outing with 007, but behind-the-scenes legal actions meant that it would be more than six years before another foot of film would turn on a Bond film. By then Cubby Broccoli had taken a backseat, placing Eon Productions in the capable hands of the next generation: Cubby’s daughter Barbara and stepson Michael Wilson. When the franchise finally emerged from the legal mire there would be a new producer, a new Bond, a new director and a new cinematographer, which is how it should be …

With change on the way, whether the older generation likes it or not, upheaval inevitably brings casualties to the elders of the filming community who sometimes find change difficult to cope with. It must be said that my twenty years of working for Cubby Broccoli and his delightful family was one of the happiest professional experiences of my filming career – genuine professional people whom I came to respect.

The only question now was, how long would it be before I also found myself struggling with the outgoing tide?

There is a strange uncertainty with the film industry whereby you can never be sure in which direction it is heading; exaggerated stories of doom and despondency rarely helping the situation. Then one day, out of the gloom, came a call from the National Film and Television School at Beaconsfield; Ernie Vincze, the head of cinematography, was asking if I would be interested teaching at the NFTS. Knowing little of the new technology which was beginning to overtake the camera department, not to mention the fact that age was fast creeping up on me, I carefully considered his tempting offer.

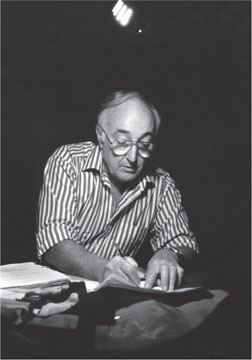

Bloodmoon

(1989): working on the script and hoping for a miracle to happen. It didn’t.

Beaconsfield had a lot to offer. Apart from finally bringing on the challenge of the complexities of the dreaded computer, which so far I had failed to come to terms with, this change in direction would help to keep me in touch with the younger generation of cinematographers who would soon join the army of the already unemployed as I prepared them for the uncertainty ahead. Then, as I contemplated my sudden interest in teaching and with little prospect of more films being offered to me, out of the blue came another call which would turn my career upside-down.

‘G’day mate, do yer fancy coming darn-under to do a film for me?’

Stanley O’Toole’s impression of an Australian accent was truly awful, as pathetic as my skills in conveying his portrayal to paper. But the surprising news was that Stanley was in Australia. The NFTS would have to be put on the back burner.

Stanley’s plan was not quite as simple as he first thought, as it would seem that the Australian film technicians’ union was unhappy with the idea of an English cinematographer coming over from the UK to film in Brisbane, explaining that they already had their own cinematographers available – which was a cheek, considering that Australian cinematographers were already working here in the UK.

At this stage my trip was put on hold, although I knew that my producer friend would not give up that easily. It turned out that my dependable supporter was actually setting up a series of small films for Australian television, where by chance he came upon a get-out clause in the union’s ruling. The accent now quickly back to normal – back to business.

‘Alec, would you consider directing a film for me?’

Hang on, did I hear that right? At first I assumed this was Stanley’s weird sense of humour, certainly not a genuine offer, but apparently there was method in his madness as it was possible for the producer to bring in an overseas director if he wished. Past experience suggested that Stanley would get his way, but when he sensed my hesitation he quickly reminded me of my capabilities when I helped him during the filming of

On the Third Day

– but that was moons ago!

Within days a parcel arrived in the post, giving my first glimpse of the ‘script’ – if you could call it that. In fact,

Bloodmoon

was absolute rubbish but, as bad as it was, Village Roadshow had accepted it. If I am honest,

Bloodmoon

with its low budget and lower artistic merit was something of an exploitation film for which Australia was particularly known at this time; one critic had even coined the phrase ‘Ozploitation’ film’. Needless to say, I passed on my thoughts to Stanley, if a little more diplomatically.

‘Our Father, who art in Heaven …’ how did I get into this awful mess?

‘Alec, I know it’s crap, so rework the storyline and make it more acceptable!’

As usual with the producer the discussion quickly ended with the phone being put down.

Stanley had thrown down the gauntlet, challenging me to improve on all of the garbage that lay before me. It was now time to learn new skills and face up to the predicament of making sense out of this ridiculous script, at the same time keeping the original story. Unfortunately the truth was that the changes required to improve this absurd storyline would require a professional scriptwriter who no doubt would have preferred to start by tearing up the old script and starting over. As that was not about to happen, all I could do was buckle down and try to develop the storyline into something I believed would be enough – just – to make it acceptable to Stanley.

Let me say I was not proud of my input or the changes made – I am not a scriptwriter. Even so, Stanley accepted all of them; my one consolation from all this nonsense was that I had been given an opportunity which would probably never be repeated – to direct a small film.

Flying to Brisbane, relaxing in the luxury of first-class travel, my thoughts were in sympathy with my new colleagues – those unfortunate directors on whom I had poured such scorn from time to time. With this script I could expect to be voted in as chairman of their exclusive club. Returning to my senses, I put all negative thoughts aside and went back to working on the script. I had no real anxieties with directing, especially as I had a cast of young unknowns with no particular names of repute to worry me, although it would be easy to understand their concerns with this preposterous story.

With my arrival at the studio it would seem that Stanley was still struggling with one scene in the script where a teacher was having an affair with one of the students. The actress pencilled in for the part had promised Stanley that she would have no problem with nudity, but even so he had reservations and would need confirmation before casting her. The solution was simple; as director, I should see the actress walking up and down naked to check that she had a good figure – ‘perks for the director’ he had assured me. Well, someone had to do it, but even so I insisted that another lady from the production office should be present. Satisfied that the actress had the required ‘merits’ on which Stanley insisted, needless to say she got the part.

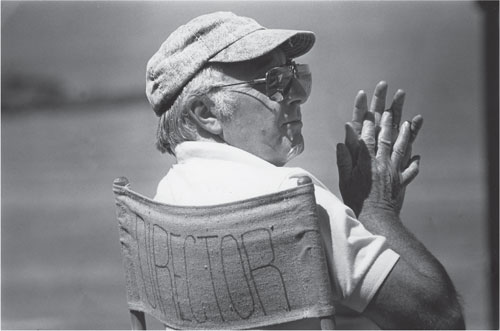

To make the story work with my very tight schedule it was necessary to plan every single scene and shot in advance as there would be no time for the luxury of filming additional sequences to salvage this pathetic script. With the help of my enthusiastic Australian crew my thorough preparation paid off, leaving little chance of being hesitant with any decisions made. Even more important, I would also be seen as positive in my judgement by both cast and crew. In all humility, after many years of working on films decisiveness would not be a problem for me; my one satisfaction would be in knowing I was capable of doing the job.

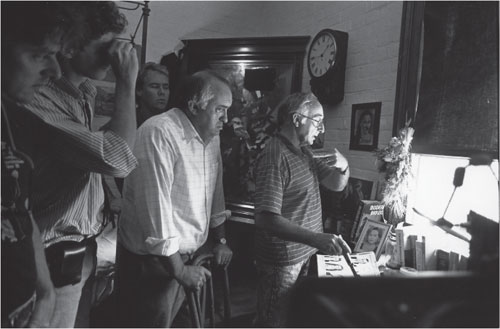

He did it! The director identifies Leon Lissek as the murderer while filming

Bloodmoon

in Australia.