Silent Spring (22 page)

Authors: Rachel Carson

Do pesticides represent a threat to the shrimp fisheries and to the supply for the markets? The answer may be contained in recent laboratory experiments carried out by the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. The insecticide tolerance of young commercial shrimp just past larval life was found to be exceedingly lowâmeasured in parts per

billion

instead of the more commonly used standard of parts per million. For example, half the shrimp in one experiment were killed by dieldrin at a concentration of only 15 parts per billion. Other chemicals were even more toxic. Endrin, always one of the most deadly of the pesticides, killed half the shrimp at a concentration of only

half of one part per billion.

The threat to oysters and clams is multiple. Again, the young stages are most vulnerable. These shellfish inhabit the bottoms of bays and sounds and tidal rivers from New England to Texas and sheltered areas of the Pacific Coast. Although sedentary in adult life, they discharge their spawn into the sea, where the young are free-living for a period of several weeks. On a summer day a fine-meshed tow net drawn behind a boat will collect, along with the other drifting plant and animal life that make up the plankton, the infinitely small, fragile-as-glass larvae of oysters and clams. No larger than grains of dust, these transparent larvae swim about in the surface waters, feeding on the microscopic plant life of the plankton. If the crop of minute sea vegetation fails, the young shellfish will starve. Yet pesticides may well destroy substantial quantities of plankton. Some of the herbicides in common use on lawns, cultivated fields, and roadsides and even in coastal marshes are extraordinarily toxic to the plant plankton which the larval mollusks use as foodâsome at only a few parts per billion.

The delicate larvae themselves are killed by very small quantities of many of the common insecticides. Even exposures to less than lethal quantities may in the end cause death of the larvae, for inevitably the growth rate is retarded. This prolongs the period the larvae must spend in the hazardous world of the plankton and so decreases the chance they will live to adulthood.

For adult mollusks there is apparently less danger of direct poisoning, at least by some of the pesticides. This is not necessarily reassuring, however. Oysters and clams may concentrate these poisons in their digestive organs and other tissues. Both types of shellfish are normally eaten whole and sometimes raw. Dr. Philip Butler of the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries has pointed out an ominous parallel in that we may find ourselves in the same situation as the robins. The robins, he reminds us, did not die as a direct result of the spraying of DDT. They died because they had eaten earthworms that had already concentrated the pesticides in their tissues.

Although the sudden death of thousands of fish or crustaceans in some stream or pond as the direct and visible effect of insect control is dramatic and alarming, these unseen and as yet largely unknown and unmeasurable effects of pesticides reaching estuaries indirectly in streams and rivers may in the end be more disastrous. The whole situation is beset with questions for which there are at present no satisfactory answers. We know that pesticides contained in runoff from farms and forests are now being carried to the sea in the waters of many and perhaps all of the major rivers. But we do not know the identity of all the chemicals or their total quantity, and we do not presently have any dependable tests for identifying them in highly diluted state once they have reached the sea. Although we know that the chemicals have almost certainly undergone change during the long period of transit, we do not know whether the altered chemical is more toxic than the original or less. Another almost unexplored area is the question of interactions between chemicals, a question that becomes especially urgent when they enter the marine environment where so many different minerals are subjected to mixing and transport. All of these questions urgently require the precise answers that only extensive research can provide, yet funds for such purposes are pitifully small.

The fisheries of fresh and salt water are a resource of great importance, involving the interests and the welfare of a very large number of people. That they are now seriously threatened by the chemicals entering our waters can no longer be doubted. If we would divert to constructive research even a small fraction of the money spent each year on the development of ever more toxic sprays, we could find ways to use less dangerous materials and to keep poisons out of our waterways. When will the public become sufficiently aware of the facts to demand such action?

F

R

O

M

S

M

A

L

L

B

E

G

I

N

N

I

N

G

S

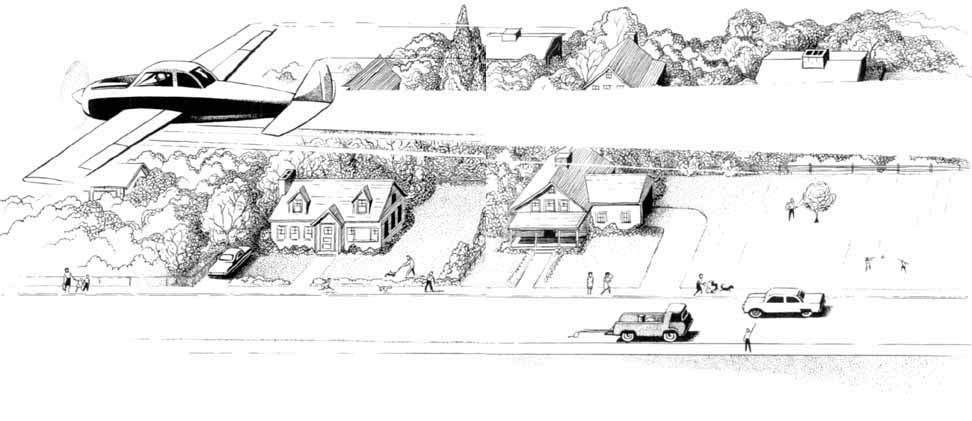

over farmlands and forests the scope of aerial spraying has widened and its volume has increased so that it has become what a British ecologist recently called "an amazing rain of death" upon the surface of the earth. Our attitude toward poisons has undergone a subtle change. Once they were kept in containers marked with skull and crossbones; the infrequent occasions of their use were marked with utmost care that they should come in contact with the target and with nothing else. With the development of the new organic insecticides and the abundance of surplus planes after the Second World War, all this was forgotten. Although today's poisons are more dangerous than any known before, they have amazingly become something to be showered down indiscriminately from the skies. Not only the target insect or plant, but anythingâhuman or nonhumanâwithin range of the chemical fallout may know the sinister touch of the poison. Not only forests and cultivated fields are sprayed, but towns and cities as well.

A good many people now have misgivings about the aerial distribution of lethal chemicals over millions of acres, and two mass-spraying campaigns undertaken in the late 1950's have done much to increase these doubts. These were the campaigns against the gypsy moth in the northeastern states and the fire ant in the South. Neither is a native insect but both have been in this country for many years without creating a situation calling for desperate measures. Yet drastic action was suddenly taken against them, under the end-justifies-the-means philosophy that has too long directed the control divisions of our Department of Agriculture.

The gypsy moth program shows what a vast amount of damage can be done when reckless large-scale treatment is substituted for local and moderate control. The campaign against the fire ant is a prime example of a campaign based on gross exaggeration of the need for control, blunderingly launched without scientific knowledge of the dosage of poison required to destroy the target or of its effects on other life. Neither program has achieved its goal.

The gypsy moth, a native of Europe, has been in the United States for nearly a hundred years. In 1869 a French scientist, Leopold Trouvelot, accidentally allowed a few of these moths to escape from his laboratory in Medford, Massachusetts, where he was attempting to cross them with silkworms. Little by little the gypsy moth has spread throughout New England. The primary agent of its progressive spread is the wind; the larval, or caterpillar, stage is extremely light and can be carried to considerable heights and over great distances. Another means is the shipment of plants carrying the egg masses, the form in which the species exists over winter. The gypsy moth, which in its larval stage attacks the foliage of oak trees and a few other hardwoods for a few weeks each spring, now occurs in all the New England states. It also occurs sporadically in New Jersey, where it was introduced in 1911 on a shipment of spruce trees from Holland, and in Michigan, where its method of entry is not known. The New England hurricane of 1938 carried it into Pennsylvania and New York, but the Adirondacks have generally served as a barrier to its westward advance, being forested with species not attractive to it.

The task of confining the gypsy moth to the northeastern corner of the country has been accomplished by a variety of methods, and in the nearly one hundred years since its arrival on this continent the fear that it would invade the great hardwood forests of the southern Appalachians has not been justified. Thirteen parasites and predators were imported from abroad and successfully established in New England. The Agriculture Department itself has credited these importations with appreciably reducing the frequency and destructiveness of gypsy moth outbreaks. This natural control, plus quarantine measures and local spraying, achieved what the Department in 1955 described as "outstanding restriction of distribution and damage."

Yet only a year after expressing satisfaction with the state of affairs, its Plant Pest Control Division embarked on a program calling for the blanket spraying of several million acres a year with the announced intention of eventually "eradicating" the gypsy moth. ("Eradication" means the complete and final extinction or extermination of a species throughout its range. Yet as successive programs have failed, the Department has found it necessary to speak of second or third "eradications" of the same species in the same area.)

The Department's all-out chemical war on the gypsy moth began on an ambitious scale. In 1956 nearly a million acres were sprayed in the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan, and New York. Many complaints of damage were made by people in the sprayed areas. Conservationists became increasingly disturbed as the pattern of spraying huge areas began to establish itself. When plans were announced for spraying 3 million acres in 1957 opposition became even stronger. State and federal agriculture officials characteristically shrugged off individual complaints as unimportant.

The Long Island area included within the gypsy moth spraying in 1957 consisted chiefly of heavily populated towns and suburbs and of some coastal areas with bordering salt marsh. Nassau County, Long Island, is the most densely settled county in New York apart from New York City itself. In what seems the height of absurdity, the "threat of infestation of the New York City metropolitan area" has been cited as an important justification of the program. The gypsy moth is a forest insect, certainly not an inhabitant of cities. Nor does it live in meadows, cultivated fields, gardens, or marshes. Nevertheless, the planes hired by the United States Department of Agriculture and the New York Department of Agriculture and Markets in 1957 showered down the prescribed DDT-in-fuel-oil with impartiality. They sprayed truck gardens and dairy farms, fish ponds and salt marshes. They sprayed the quarter-acre lots of suburbia, drenching a housewife making a desperate effort to cover her garden before the roaring plane reached her, and showering insecticide over children at play and commuters at railway stations. At Setauket a fine quarter horse drank from a trough in a field which the planes had sprayed; ten hours later it was dead. Automobiles were spotted with the oily mixture; flowers and shrubs were ruined. Birds, fish, crabs, and useful insects were killed.

A group of Long Island citizens led by the world-famous ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy had sought a court injunction to prevent the 1957 spraying. Denied a preliminary injunction, the protesting citizens had to suffer the prescribed drenching with DDT, but thereafter persisted in efforts to obtain a permanent injunction. But because the act had already been performed the courts held that the petition for an injunction was "moot." The case was carried all the way to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear it. Justice William O. Douglas, strongly dissenting from the decision not to review the case, held that "the alarms that many experts and responsible officials have raised about the perils of DDT underline the public importance of this case."

The suit brought by the Long Island citizens at least served to focus public attention on the growing trend to mass "application of insecticides, and on the power and inclination of the control agencies to disregard supposedly inviolate property rights of private citizens.

The contamination of milk and of farm produce in the course of the gypsy moth spraying came as an unpleasant surprise to many people. What happened on the 200-acre Waller farm in northern Westchester County, New York, was revealing. Mrs. Waller had specifically requested Agriculture officials not to spray her property, because it would be impossible to avoid the pastures in spraying the woodlands. She offered to have the land checked for gypsy moths and to have any infestation destroyed by spot spraying. Although she was assured that no farms would be sprayed, her property received two direct sprayings and, in addition, was twice subjected to drifting spray. Milk samples taken from the Wallers' purebred Guernsey cows 48 hours later contained DDT in the amount of 14 parts per million. Forage samples from fields where the cows had grazed were of course contaminated also. Although the county Health Department was notified, no instructions were given that the milk should not be marketed. This situation is unfortunately typical of the lack of consumer protection that is all too common. Although the Food and Drug Administration permits no residues of pesticides in milk, its restrictions are not only inadequately policed but they apply solely to interstate shipments. State and county officials are under no compulsion to follow the federal pesticides tolerances unless local laws happen to conformâand they seldom do.