Singing Hands

Authors: Delia Ray

Delia Ray

C

LARION

B

OOKS

New York

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Text copyright © 2006 by Delia Ray

The text was set in 12-point Minister Light.

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, NY 10003.

Printed in the U.S.A.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ray, Delia.

Singing hands / by Delia Ray.

p. cm.

Summary: In the late 1940s, twelve-year-old Gussie, a minister's daughter,

learns the definition of integrity while helping with a celebration at the

Alabama School for the Deafâher punishment for misdeeds against her

deaf parents and their boarders.

ISBN 0-618-65762-2

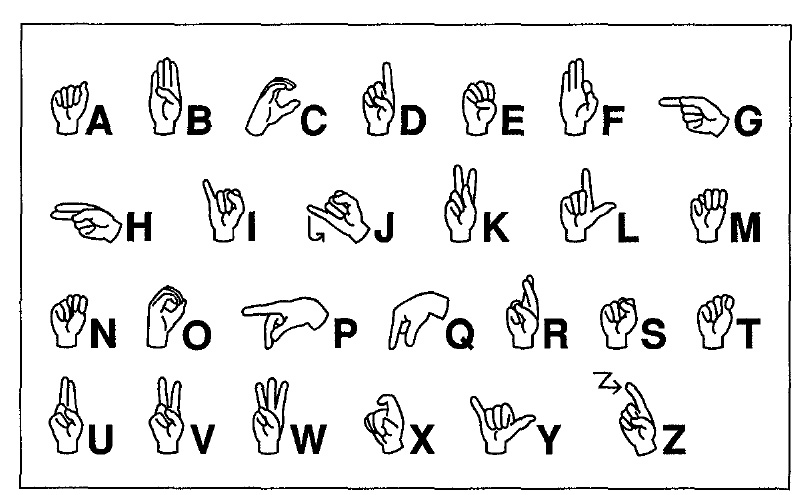

[1. Conduct of lifeâFiction. 2. DeafâFiction. 3. People with disabilitiesâ

Fiction. 4. American Sign LanguageâFiction. 5. Family lifeâAlabamaâ

Fiction. 6. ClergyâFiction. 7. AlabamaâHistoryâ20th centuryâFiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.R2101315Sin 2006

[Fic]âdc22 2005022972

ISBN-13: 978-0-618-65762-9

ISBN-10: 0-618-65762-2

MP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

For Robert and Estelle

and their daughter Roberta,

who keeps her family's stories alive

Up until the summer of 1948, when I was twelve, probably the worst thing I ever did was hum in church. I started out humming quiet songs like "Beautiful Dreamer," letting the notes ease out in a slow, whispery voice. I would glance sideways and check over my shoulder for any "Ears" who might have slipped into the congregation. Then, if everybody else around me kept staring straight ahead, with their hands folded neatly over their pocketbooks and prayer books, caught up in another one of Daddy's sermons, I would try humming louder. My little sister, Nell, sat beside me with no more than a tiny smile playing along the corners of her perfect red lips. I knew she would never tattle. Nell and I were only fifteen months apart, and we had an unspoken rule: the sister who tattled would endure weeks of shame and loneliness.

After a few Sundays without getting caught, I started humming louder and livelier songsâ"I'm Looking Over a Four-Leaf Clover" or "Shoo Fly Pie and Apple Pandowdy." Seeing my lips pressed together tight and a sweet, blank expression locked on my face, no one at Saint Jude's Church for the Deaf had any idea I was holding a private humming concert.

I knew I was probably going too far the day I decided to perform all four verses of "Dixie" right through Holy Communion. But I couldn't seem to stop myself. Nothing else exciting was happening that summer. And it felt heavenly to burst out with noise in Daddy's silent, sweltering church, where the only other sounds were flies buzzing against the windowpanes and the streetcar rumbling along Jefferson Avenue.

I kept humming even when we all started down the aisle toward the altar. Unfortunately, my sixteen-year-old sister, Margaret, had had her fill of my humming. From her usual spot in the back row of the choir, she glared at me as if she could shoot poisoned darts from her eyes. When that didn't work, she threw herself into a small coughing fit to try to get me to hush up. But nobody in the choir noticed her sputteringânot even Mother, who was the unofficial director of the group. She and the other choir ladies were too busy signing the words to the Communion hymn, working to keep their graceful hands in unison.

When Daddy reached my spot at the altar railing, he smiled at me and placed a dry Communion wafer in my cupped palm. I paused "Dixie" only long enough to swallow it, wash down the postage-stamp taste with a sip of wine, and make the sign for Amen. Then, with the most powerful hum I could muster, I started into the refrainâthe "Away, away, awaaaaaay down sooooooouth in Dixie" part. I winked at Margaret on the way back to my seat. Ha! There was nothing she could do right in the middle of the serviceâright in the middle of Saint Jude's, smack dab in the middle of a sanctuary packed full of deaf people who worshiped their deaf minister, Reverend Davis, as well as his dear deaf wife, Olivia, and their three lovely hearing daughters, Margaret, Nell, and, in the middle, meâGussie, secret humming goddess of the South.

Of course, my unusual performance of "Dixie" in church should have been my grand finale that summer, the ultimate test of what I could do without getting caught. But it wasn't. Humming was just the warmup.

For a minister's family, church never ends with the last Amen. After services every Sunday, it was our job to stand outside next to Daddy and Mother, nodding and shaking hands with everyone as they filed down the steps. In between smiling and signing good morning, Margaret scolded me. She seemed more annoyed with me than usual, probably because of the heat. Even though it was only June and the beginning of summer vacation, Birmingham already felt like a stew pot. The smell of hot tar drifted up from Jefferson, and I could see tiny beads of sweat gleaming on Margaret's upper lip.

"What were you thinking?" she fumed. "We won't even talk about how sacrilegious you are. But just imagine how horrified Daddy would be if he could hear you. What if somebody's hearing relatives or kids were there? What if the bishop had decided to visit today?"

"All the other kids were in Sunday school," I said. "And there weren't any other Ears around. I checked."

Margaret rolled her eyes with disgust.

Just then I spotted Mr. Runion working his way toward us. He was grinning and bobbing his head, like always. "Oh, boy," I breathed. "Here it comes." Nell let out a little whimper.

For as long as I could remember, old Mr. Runion had tried to make us laugh by shaking our hands so hard and so fast that our arms turned limp as noodles. I know I must have laughed at the trick when I was six or seven. But now, after endless Sundays of being cranked and wiggled and jolted like a jackhammer, I was tired of the joke.

Nell pretended to be coy. She quickly pushed her fist into the pocket of her skirt, but Mr. Runion stood in front of her and held out his hand until she had to surrender. Nell smiled weakly until her turn at arm rattling was over. Mr. Runion let out one of his high, giggly laughs, then moved on to Margaret.

Margaret didn't even wait until he had finished with her before she started nagging me again. "I'm telling you, Gussie," she said, her voice shaking along with her arm, "you went too far today with all that loud humming. I'll have toâ"

Mr. Runion was standing in front of me now. But this time I was ready for him. I grabbed hold of his knobby hand and shook back for all I was worth, not letting loose until he pulled away. Mr. Runion looked surprised. He blew on his thick fingers and flexed them as if they had been stuck in a bear trap. "Good grip," he signed, and then moved away.

Nell snickered, but Margaret didn't even congratulate me for setting Mr. Runion straight. She was still lecturing. "I mean it, Gussie," she went on, "if you keep this up, I'll have to tell Daddy."

"Uh-huh, and if you do," I said sweetly, "I'll have to tell Daddy about the time you and Anna Finch sneaked the Communion wine out of the kitchen pantry and had a little tasting party."

"That was three years ago," Margaret snapped, momentarily forgetting to keep smiling and talking through her teeth.

Mother shot us a hard look and Margaret rubbed her hand across her mouth as if she could erase our conversation. Mother's lip-reading skills were legendary. As a young student at Gallaudet, the college for the deaf in Washington, D.C., she had won every lip-reading contest she ever entered.

Mother and Daddy were so good at knowing what we were saying, even when we mumbled or muttered, that I often wondered if they had been playing some sort of strange, elaborate trick on us all these years. Maybe they were just pretending to be deaf, I sometimes thought. Supposedly, Mother had lost her hearing as a baby after a terrible case of scarlet fever, and Daddy told us he had been struck deaf by lightning when he was eight as he stood on his front porch watching a fierce thunderstorm churning up the sky. But just maybe

all those stories were lies.

Maybe they were just waiting to catch us in the act, to catch us when we screamed up and down the stairs at each other before school every morning or played the radio too loud or gossiped about the ladies who rented the spare bedrooms in our big creaky house on Myrtle Street.

Mother gave us another frown, then turned away. "See?" said Margaret. "You're going to get us both in trouble."

I studied Mother's face for a minute, checking to see if anything was amiss. But I could tell she had already forgotten about any problems Margaret and I might be having. As usual, she and Daddy had all the worries of their congregation to attend to. I watched their hands flying and sympathetic expressions flitting over their faces as they patiently greeted one person after another. There was the young Jamison couple, who proudly hovered over their new baby wrapped in two layers of blankets even though it was hot as hellfire. They wanted to ask Mother endless questions about raising a hearing child. How would the baby learn to talk with deaf parents? When should children be taught to make their first sign?

Then along came Mrs. Thorp, a crabby widow who walked with a jerky limp and had to spend five minutes every Sunday describing the pain in her left heel to anyone who could stand to pay attention. Everyone knew her pain came from stomping on Kanine Kare dog food cans after her snorty little pug, Bertie, finished each meal. But Mrs. Thorp refused to believe that flattening cans could be the cause of her trouble. "I had this limp long before Bertie came along," she claimed, chopping out her words with angry fingers.

I heaved a long sigh. Usually we would be on the way to Texas by now to stay with Mother's sister, Aunt Gloria. Until this year, we had spent most of every summer vacation in Texas. The tradition had started when we were babies, and Mother and Daddy had realized that we might never learn to talk properly if we had only their speaking voices to imitate. So each summer Aunt Glo and Uncle Henry became our substitute speech teachers. Aunt Glo, who could never have children of her own, was more than happy to pour all of her lost years of mothering into two short months with her adoring nieces.

But all that was behind us this year. The As and Bs on our report cards assured Mother that our grasp of the English language seemed to be just fine, and with Daddy gone more and more these days, she hated to give up our company for the whole summerâas well as the extra hands for chores. Then Margaret had to clinch the argument by piping up that she was getting too old to be shipped off for the entire summer, and she couldn't possibly endure the separation from her precious crowd of beaus and girlfriends for that long.

So it was decided. Instead of two months in Texas, we would be staying only one measly week ... at the end of August. Now the thought of spending the majority of our vacation in humdrum old Birmingham, without Aunt Glo's barbecued spareribs or the lazy afternoons at her country club, made the time stretch out in my mind like an endless desert.

"Who's that?" whispered Nell. A tall, serious man in a striped bow tie had cornered Daddy.

I shrugged. I had never seen him before. Daddy was nodding at him so patiently, even though I knew he must be melting in his stiff white collar and layers of vestments. Then he touched the stranger's elbow and led him back into the sanctuary toward his cramped little office, where he always took people for private conversations.

"Shoot," Nell said, following my gaze. "Guess that means Daddy won't be coming to Britling's with us."

"Nell," I said peevishly, "when was the last time you remember him coming to Britling's Cafeteria with us?" Nell knew that Daddy had only an hour's break before he had to rush across town to hold services for his colored deaf congregation at Saint Simon's.

"I know," Nell said meekly. "I was thinking he might want to since we just got out of school and all, and it's the beginning of vacation andâ"

"Huh," I grunted. "Fat chance."

"He can't help it," Margaret cut in. "It's his

job.

He has to take care of people."

"You mean

deaf

people," I muttered. I stared at all the hands flashing around me, moving so fast I could never understand everything they were saying no matter how hard I tried to learn more signs. And the expressions on their faces! They were so ... so exaggerated, leaping from joy to dismay, barely anything in between. Sometimes I felt as if I had been dropped down in the middle of a secret club, one where my father, Reverend Davis, was president.

I would never belong to the club. I wasn't deaf. I wasn't a natural at signing like Margaret or pretty as a porcelain doll like Nell. And I certainly didn't have the heart full of bounty that Daddy had preached about in his sermon that morning. The only thing I felt like doing was shaking an old man's hand until his teeth rattled.