Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (19 page)

Read Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon Online

Authors: Stephan V. Beyer

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Religion & Spirituality, #Other Religions; Practices & Sacred Texts, #Tribal & Ethnic

RECEIVING THE MASTER'S PHLEGM

The shamanic coronacion, initiation, consists, in part, of the master shaman

transferring magical phlegm through his or her mouth to the apprentice: the

mouth of the master shaman regurgitates mariri, which is ingested by the

mouth of the apprentice. During an ayahuasca ceremony with don Roberto,

he gave me a portion of his phlegm, for me to keep and nurture in my chest

while I was gone and to protect me from attacks by wicked or jealous sorcerers. This was my coronacion in the ayahuasca path; receiving the llausa of the

maestro ayahuasquero, he said, is reserved for those who are "learning the

medicine."

First he put his llausa or flema, phlegm, into my body through my corona,

the crown of my head. Then he shook his shacapa rattle all over my body, protecting and preparing my body to hold the medicine. He brought his phlegm

up from his chest with a series of dramatic burps and belches; then he placed

his mouth over mine and transferred into my mouth a slippery cohesive globule about a half inch in diameter, which I swallowed. This llausa went into my

chest, he said, to join the llausa he had put in through my corona. He told me

that I must smoke mapacho every day to keep the llausa in place, to nurture

this seed he had planted inside me; in the same way, a Shuar shaman must

drink tobacco juice every few hours, to nurture the tsentsak, magic darts, given by the master shaman, and keep them fed so that they will not leave him.9

Giving me his phlegm, don Roberto said, was like planting grass; it was up to

me to keep it fertile. "Now," he said, "you will have the medicine for the rest

of your life."

In addition to his phlegm, don Roberto gave me two of his spirit animals

for my protection-the otorongo, the tawny jaguar, and the yanapuma, the

black jaguar. Just as I must nurture my phlegm by smoking mapacho, I should

maintain my connection with the jungle spirit protectors by continuing to

drink ayahuasca. As we will see, when dona Maria was attacked by don X, part

of the attack was to separate her from her protectors by making it hard for her

to drink ayahuasca.

Dona Maria elaborated on the nature of this gift. Now that I have mariri, she said, I will be able to feel a pulsation on my body where I am about to be

attacked. This polpito-the word means both a physical throb and a psychological hunch-is a warning to me. If I have this feeling, for example, before

a meeting, I will know that a person there has bad intentions toward me. If

someone at the meeting does not shake hands with me-if the person just

waves and says hello or touches the back of my hand-then I know the person

is a brujo. Sorcerers, dona Maria told me, will not shake my hand, for then

they would be revealed to my touch.

To nurture the seed don Roberto planted in my chest, and to build up my

own store of magical and protective phlegm, I should be smoking mapacho

every day. I should be drinking ayahuasca under the direction of a maestro

ayahuasquero, but dona Maria and don Roberto understand that it is difficult

to do that in North America. The longer I am away from the medicine, however, the more sickness and evil of all kinds will build up in my body; when I

return-as has happened before after a long absence-I can anticipate a truly

spectacular purga. I should be learning icaros, sacred songs-first those of my

own maestro ayahuasquero, many ofwhich I have recorded on tape, and then,

eventually, my own, which the plants will teach me. Dona Maria told me to

first hum the melody or to whistle it in the breathy whispering whistle called

silbando; the words are less important than the melody. Any time I sing their

icaros, dona Maria and don Roberto will be by my side. Many times when

she goes to sleep, Maria walks far in her dreams; she will come and sit by my

side, and I will fear nothing and nobody, she said, for the medicine grants a

corazon de acero, a heart of steel.

INITIATION IN THE UPPER AMAZON

Similar conceptions occur throughout the Upper Amazon. One of Luna's

shamans told how his teacher, after having blown tobacco smoke into both

his apprentice's nostrils using a toucan beak, regurgitated his yachay into a

little bowl and gave it to his apprentice to drink, together with tobacco juice.'°

When a Siona shaman teaches an apprentice his visions and songs, he imparts some of his dau to him."

For the Shipibo-Conibo, quenyon, the shaman's power substance, is a

sticky paste-like phlegm in which are embedded small arrows or the thorns of

spiny palms. The master shaman passes this phlegm to an apprentice by swallowing a large amount of tobacco smoke and bringing up the phlegm from

his chest to his mouth, from which the apprentice sucks it out, nightly, for a week. The phlegm accumulates first in the apprentice's stomach, where it

is believed to be harmful; to make it rise to the chest and remain there, the

apprentice drinks tobacco water and swallows tobacco smoke. If the phlegm

rises to the mouth, the apprentice must swallow it again, in order to ensure

that the phlegm does not leave the body through the mouth or other orifice.12

Similarly, among the Shuar, the master shaman vomits tsentsak, magic

darts, in the form of a brilliant substance. The master shakes the shinku leaf

rattle over the apprentice's head and body, singing to the tsentsak, makes profound throat-clearing noises, and spits out the phlegm on the palms and the

backs of the apprentice's hands, and then on the chest, head, and finally the

mouth; it is then swallowed-painfully-by the apprentice.13 Shuar shaman

Alejandro Tsakimp describes his initiation by his aunt, Maria Chumpa, whom

he approached "to study how it is to be a shaman of the woman's way": "The

shamanism of my aunt Maria was different from that of Segundo and Lorenzo

because they blew on the crown of my head, and they gave me the ayahuasca

to concentrate. But my aunt gave me phlegm, like this, taking out her chuntak.

She made me put it in my mouth and swallow it. "14

Among the Iquitos, the materialized power of the shaman is described as

a ball of leaves inside the body, which can be transmitted by a bird or passed

mouth to mouth from the master shaman to the apprentice.15

The Achuar apprentice drinks ayahuasca and inhales tobacco juice with the

master shaman, who then blows darts into the apprentice's head and shoulders and between the fingers, and then puts his saliva into the apprentice's

mouth, speaking the names of the different kinds: "Take the saliva of the anaconda! Take the saliva of the rainbow! Take the saliva of iron!"-all of which

the apprentice must swallow and not vomit. A shaman recalls his initiation:

"My stomach heaved and all the saliva rose into my mouth. I almost spat everything out, but managed to swallow it down.",'

Anthropologist Marie Perruchon tells an interesting story about her own

initiation as a Shuar uwishin. She was, she says, quite concerned about swallowing the phlegm of her master, Carlos Jempekat, who was also her brotherin-law; she thought that this-combined with the emetic effect of ayahuasca-would cause her to throw up the phlegm immediately. Apparently Carlos

sensed her hesitation; at her initiation, he blew the tsentsak into the crown of

her head, rather than giving them to her through her mouth. Both methods

seem to have been acceptable; receiving shamanic power by blowing is attributed to Canelos Quichua shamans, whom the Shuar hold in high esteem.

Carlos Jempekat said that tsentsak received in phlegm are less liable to leave the body accidentally than those received en aire, by blowing: "Sometimes

it is enough to stumble," he said, "and, whoops, the tsentsak leave."I7 It is

also possible to receive tsentsak in a dream, instead of receiving them from a

shaman.,'

A Tukano apprentice receives the darts-the sharp thorns of a spiny

palm-through the skin on the inside of the left forearm. The teacher presses upon these thorns with a cylinder of white quartz, with the handle of the

gourd rattle, and finally with his clenched fist, through which he blows to

make the splinters enter the arm, into which they disappear. These darts can

then be projected at an enemy with a violent movement of the arm; they are

placed in the left arm so that they are not hurled inadvertently during a fight or

quarrel. The shaman also places darts on the apprentice's tongue, and blows

them into the apprentice's body through his fist, so that the apprentice can

then safely suck the sickness from a patient's body.19

THE INITIATION DIET

In order to allow the tsentsak to mature and keep them from leaving the body,

the Shuar apprentice must undertake a severe diet-only green plantains for

the first week, remaining in bed without coughing or speaking loudly, with

one hand always covering the mouth. The apprentice also drinks tobacco juice

night and day to feed the darts. After a week the apprentice may get out of bed

and take a bath, but must stay inside the house or in shady spots in the courtyard for the next few weeks. The apprentice is also allowed to eat some vegetables, fruits, and domestic chicken. The idea is to avoid anything-animal fat,

spices, laughing, coughing, shouting, sex-that may heat the body and drive

out the darts. Ideally, these restrictions are kept for about a year, during which

time they are slowly relaxed, one at a time. The apprentice may not touch anyone else; even the chickens the apprentice eats have to be sexually inactive.20

The Achuar initiate has to stay at home for at least a month, without moving, drinking tobacco water every day, without sex, so that the darts can get

used to their new host.21 The same is true for the newly initiated Tukano shaman. For several weeks or months, he may not eat meat, or fat grubs, or peppers-only certain fish, manioc, and thin soups. Even the preparation of such

foods near the house is prohibited. And sexual abstinence continues; he must

have no sex and must avoid contact with menstruating women. The new shaman must avoid any loud or shrill or sudden noises, which would drown out

the voices of the spirits.22

SELF-CONTROL

There is a theme woven through the shamanisms of the Upper Amazon-that

human beings in general, and shamans in particular, have powerful urges to

harm other humans. The difference between a healer and a sorcerer is that the

former is able to bring these urges under control, while the latter either cannot or does not want to.

Thus, what distinguishes a healer from a sorcerer is self-control. This

self-control must be exercised specifically in two areas-first, in keeping to

la dieta, the restricted diet; and, second, in resisting the urge to use the magical darts acquired at initiation for frivolous or selfish purposes. Shamans who

master their desires may use their powers to heal; those who give in to desire,

by their lack of self-control, become sorcerers, followers of the easy path.23

As with la dieta, a significant part of the initiation process is for the new

shaman to demonstrate the self-control that separates healers from sorcerers. Self-control is manifested in resisting the immediate urge to use newly

acquired powers to cause harm. Among the Shuar, there is a sentiment that

becoming a shaman-acquiring tsentsak, darts-creates an irresistible desire to do harm, that "the tsentsak make you do bad things." Shuar shamans

dispute this. While the tsentsak indeed tempt one to harm, the desire can be

resisted; those who "study with the aim to cure" become healers.24

Shuar shaman Alejandro Tsakim Suanua describes one of these temptations as the urge to try out the new darts on an animal-"a dog or a bird,

anything that has blood." Once one does that, once one "starts doing harm,

killing animals, one cannot cure" but, rather, becomes a maliciador, sorcerer.25

Similarly, the Desana believe that sorcery is very dangerous, apt to rebound on

its practitioner, and to be used only for revenge on a sorcerer who has killed a

family member. It is the untrained person, the novice, who causes sicknesswho lacks the self-control imposed by the shamanic initiation, who experiments with evil spells, who uses them carelessly and irresponsibly, just to see

if they work .21

This self-control is often expressed in terms of regurgitation and reingestion of shamanic power. After a month of apprenticeship, a tsentsak comes

out of the Shuar apprentice's mouth. The apprentice must resist the temptation to use this tsentsak to harm his enemies; in order to become a healing shaman, the apprentice must swallow what he himself has regurgitated.27

Among the Canelos Quichua, the master coughs up spirit helpers in the form

of darts, which the apprentice swallows. Here, too, the darts come out of the apprentice's body and tempt him to use them against his enemies; again, the

apprentice must avoid the temptation and reswallow the darts, for only in this

way can he become a healing shaman .21

This self-control is also sometimes put in terms of turning down gifts from

the spirits. The spirits of the plants may offer the apprentice great powers and

gifts that can cause harm. If the apprentice is weak and accepts them, he will

become a sorcerer. Such gifts might include phlegm that is red, or bones, or

thorns, or razor blades. Only later will the spirits present him with other and

greater gifts-the gifts of healing and of love magic.29

And sometimes self-control develops through the moral intervention of

the healing plants themselves. Shipibo shaman don Javier Arevalo Shahuano

decided to become a shaman at the age of twenty, when his father was killed

by a virote, magic dart, sent by an envious sorcerer. "I wanted to learn in order to take vengeance," he says. It was only during his apprenticeship that he

learned self-control. "Bit by bit, through taking the very plants I had intended

to use for revenge," he says, "the spirits told me it was wrong to kill and my

heart softened. "3°

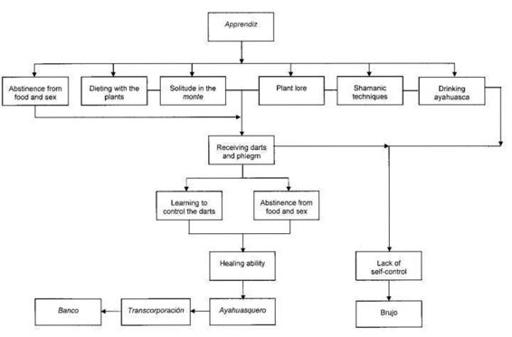

FIGURE 6. The path of the ayahuasquero.