Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (3 page)

Read Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon Online

Authors: Stephan V. Beyer

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Religion & Spirituality, #Other Religions; Practices & Sacred Texts, #Tribal & Ethnic

This book is based on two remarkable healers of the Upper Amazon-my

teachers don Roberto Acho Jurama and dona Maria Luisa Tuesta Flores. The

purpose of the book is to try to understand who they are and what they do,

by placing them in a series of overlapping contexts-as healers, as shamans,

as dwellers in the spiritual world of the Upper Amazon, as traditional practitioners in a modern world, as innovators, as cultural syncretists, and as

individuals.

DON ROBERTO

Don Roberto Acho Jurama lives much of the time in the port town ofMasusa,

at the mouth of the Rio Itayo, in the Mainas district, not far from Iquitos. Like

many mestizos, he often leaves the city for extended periods to return to his

jungle village and tend his chacra, his garden, cleared from the jungle every few

years by slashing and burning. In Masusa, don Roberto's thatched wooden

house is at the end of a dirt street, alternately dusty and muddy; the house can

be easily recognized by the pink and purple jaguar painted on its front wall.

Don Roberto holds healing ceremonies at his house on Tuesday and Friday

evenings, the same days as other mestizo healers; he is also on call at almost

any time for brief healings. The number of participants at his ceremonies varies from a few to a dozen or so. He also performs healing ceremonies, often

with dona Maria when she was alive, for ayahuasca tourists, in a large tourist

lodge in the jungle about two hours by boat from Iquitos. These ceremonies

are open as well to any local person who wants to attend; thus the number of participants-including local Bora, Yagua, and Huitoto Indians, as well as

mestizos-can often be greater than at don Roberto's own private ceremonies. He is, in many ways, an Amazon traditionalist, certainly as compared

to dona Maria. He cures by shaking his leaf-bundle rattle, blowing tobacco

smoke, and sucking from the body of his patient the magic darts that have

caused the illness-shacapar, soplar, and chupar, the foundational triad of Amazonian shamanism. Thus, much of what he does as a healer is recognizably

similar to shamanic practices found among indigenous peoples throughout

the Upper Amazon.

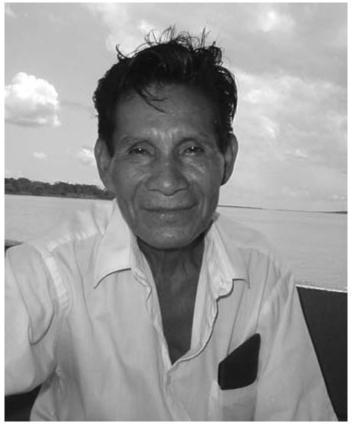

FIGURE 2. Don Roberto.

He is, as dona Maria described him, flaquito, wiry, compact, "like iron," she

said; he is thin because he keeps la dieta, the sacred diet. Don Roberto has an

intense gaze and a quick smile; he is serious about his work, but not serious

about himself. As dona Maria put it, he is a buen medico, a good doctor, "who

learned everything from ayahuasca."

Don Roberto was born on June io, 1946, in the town of Lamas in the province of San Martin-the same town in which dona Maria was born, and a

traditional home of powerful shamans. His father, Jose Acho Flores, was a

carpenter and also a banco tabaquero-a healer of the very highest level who

achieved visions and contacted the spirits through drinking infusions of

potent tobacco. He had three brothers, all of whom had died by the time I

met him; his father too was dead, while his mother was alive in the town of

Punchana.

Roberto went to school through the seventh grade. His uncle, don Jose

Acho Aguilar, was an ayahuasquero, and Roberto became an apprentice to his

uncle at the age of fourteen. He became a shaman, he says, because, when

he first drank ayahuasca, he saw things, which he enjoyed, and he wanted to

learn more. Interestingly, neither don Roberto nor dona Maria reported that

an illness or other crisis led them to become shamans. Dona Maria was, apparently, born with her visionary gift, which manifested itself when she was a

young girl; don Roberto apprenticed himself out of curiosity, and discovered

his talents as he grew in skill.

At the age of sixteen, Roberto began to work by himself. As his teacher got

older, Roberto explains, his fuerza, power, diminished, and so he transferred

his power to Roberto. That is why it is so important to Roberto for his son

Carlos to follow in his footsteps; when Roberto's power starts to decline, he

can transfer it to his son. During his apprenticeship, Roberto learned to dominar la medicina, master the medicine; he learned many plants, learned how to

prepare ayahuasca, learned how to conduct the ceremony. After two years, his

uncle said, "You are ready to work with ayahuasca by yourself." Such a twoyear apprenticeship was considered very quick.

Roberto's uncle was his only teacher. To master the ayahuasca path, Roberto says, one must find the right maestro ayahuasquero and never change.

"Some teachers don't know much," he warned me. "Some don't teach all they

know, or have ulterior motives."

Roberto currently works as a carpenter, making furniture and boats, and

only part time as a shaman; you cannot earn a living these days as a shaman,

he says. Don Roberto had lived, unmarried, for some time with a woman who

died while still childless; later he married Eliana Salinas, the mother of his

eight children. The second youngest child is Carlos, don Roberto's pride and

joy, who is studying with his father to become a shaman. Roberto is teaching

his son in just the way he himself had been taught by his uncle. He took over

his son's training when he discovered that Carlos was being deceived by another teacher with whom he was drinking ayahuasca: "The medicine was not

staying in him."

Don Roberto and Eliana moved from Roberto's jungle chacra to the town

of Punchana, where they lived for eighteen years, although, like many urbanizing mestizos, they continued to spend a good part of the year in the jungle.

They lived in the town so that their children could attend secondary school,

which don Roberto could afford, since he earned a good living as a carpenter.

Don Roberto is my maestro ayahuasquero, my teacher on the ayahuasca

path. He was never as loquacious as dona Maria; but it is his phlegm that I carry in my chest, which has transformed me and turned me in directions I

would never have guessed. He taught me how, on my own path, to be a healer.

Don't set a price, he said: Never turn away the poor. Do your healing. Trust the medicine.

DONA MARIA

Don Roberto constructs his life as essentially eventless, linear, uninterrupted by

dramatic life-changing events. He apprenticed with his uncle; he learned how

to heal from the plants; he goes on healing and teaching. Dona Maria, on the

other hand, viewed her life as having had three dramatic turning points-her

coronaci6n, initiation, as a healer, during an extended dream; the first magical

attack against her and her subsequent ayahuasca apprenticeship with don Roberto; and the second attack, launched against her by a shaman we will here

call don X, which ultimately, after the passage of several years, proved fatal.

This story is worth telling for several reasons. Dona Maria's eclecticism

and syncretism are in fact not unusual among mestizo shamans. Indeed, her

early work as an oracionista, prayer healer, contained a number of practices

found in more traditional mestizo shamanism, just as her later work as an

ayahuasquera contained elements of her earlier work, influenced by both folk

Catholicism and traditional Hispanic medicine. Her life vividly illustrates the

risks and joys of being a healer in the Upper Amazon.

Psychologist and novelist Agnes Hankiss discusses the way in which, in

the narration of a life history, certain episodes are endowed with symbolic

significance that in effect turns them into myths. She says that this is a neverending process, for the adult constantly selects new models or strategies of

life, by which the old is transmuted into material useful for the new-the new

self and the new situation. Everyone attempts, "in one way or another, to build

up his or her own ontology."' Daphne Patai, reflecting on her experience interviewing sixty women in Brazil, writes that "the very act of telling one's life

story involves the imposition of structure on experience. In the midst of this

structure, a subject emerges who tends to be represented as constant over

time. "I The women she interviewed, she says, "were telling me a truth, which

reveals what was important for them."3

The same is true for doiia Maria's story. When she was my teacher, she

mythologized her past, centering on her three turning points, all of which

validated her career as a healer and practitioner of pura blancura, the pure

white path. Dona Maria was not a simple person, and certainly not a saint;

she was genuinely warm, giving of her knowledge, impatient, dramatizing, complaining, generous, fussy, proud, unassuming, earthy, demanding, motherly. She lived as a healer in the disorderly landscape of the soul.

Childhood and Initiation

She was born on September 15, 1940, in the town of Lamas in the province

of San Martin. Don Roberto came from the same town, although Maria did

not meet him until many years later. Her father was a fisherman as well as

a tabaquero, drinking infusions of tobacco to induce visions; he also possessed, as we will see, two piedras encantas, magical stones, one of which was a

demonio, an evil spirit. Maria had three brothers and three sisters. Two of her

brothers were killed-one murdered in a pathetic drunken robbery, the other

robbed and murdered on a boat, struck on the head by a paddle and dumped,

either dead or unconscious, into the water. Maria knew what happened, she

told me, because she had seen both murders in her visions.

Dona Maria began her healing career as an oracionista, a prayer healer. Her

youth was filled with dreams and visions of angels and the Virgin Mary. She

delighted in working with children; when she retrieved the soul of a child, lost

through sudden fright, the soul would appear to her as an angel. She did not

drink ayahuasca until she was twenty-five, when, injured in a magical attack

by a vengeful sorcerer, she first apprenticed herself to don Roberto, already

at that time a well-known ayahuasquero. Toward the end of her life, she frequently joined don Roberto in his healing ceremonies for the tourist lodge.

She did not herself perform regular Tuesday and Friday ceremonies; she

would go-as she always had-wherever her healing powers were needed.

She remembered her early childhood as made idyllic by her visions and

dreams. When she was seven years old, she had her first dream of the Virgin Mary-Maria called her hermana virgen, sister virgin-who began to teach

her how to heal with plants. From that time on, she frequently had dreams in

which either the Virgin Mary or an angel appeared to her. The Virgin would

appear as a young and very beautiful woman; show her the healing plants,

especially those for protection against malignos, evil spirits of the dead; and

teach her the plants to cure specific diseases. The angel would appear and tell

her where in the area there was a child who was sick and needed her help. She

then went to the house of the child and told the family what plant would cure

the illness and how to prepare it. In one dream, she was told that she must

heal one hundred babies ofmal de ojo, the evil eye; and she understood that her

work was to be the healing of children.