Sink it Rusty (3 page)

Authors: Matt Christopher

From a short distance ahead of him, Rusty heard them reply. “Right here, Rusty!”

He hurried and caught up with them. He panted. Even though the air was bitter cold, his face was hot as fire.

“Here's the first trap,” said Joby at last.

It was near the entrance of a wide hole in the ground. Leaves were spread over it. It wasn't sprung.

“That's a weasel hole,” said Joby. “Dad says weasels are hard to catch. I believe it!”

He led Corny and Rusty to three other traps. One was snapped. Joby looked at it excitedly, but whatever had snapped it wasn't

around now.

“That's a raccoon hole,” explained Joby. “Dad told me that snapping a trap is a favorite trick of a coon's. I'll keep after

him, though, until I catch him.”

Rusty laughed. “Maybe he'll forget to play tricks some day.”

“I hope!” said Joby.

He opened the jaws of the trap again, set it, and placed it near the mouth of the hole. Then he carefully covered it with

leaves.

“I'll be back tomorrow, Mr. Coon!” he said.

They walked on. Soon Rusty heard the rippling waters of a creek. A few moments later they arrived at its bank. The water was

shallow. Rusty saw no place where they could walk across, except a log stretched over the creek like a bridge.

Rusty stared as Joby and Corny walked on it to the other side. He got on it, took three steps, then stopped.

“Come on, Rusty!” yelled Joby. “You can make it!”

He took another step, then looked along the log. It wasn't very big around. Some of

its bark had been stripped off. There was about six feet of space between it and the water underneath. If he slipped —

Rusty shuddered and backed off. Joby and Corny laughed.

I'll try it on my knees, he thought.

He got down on his knees, crawled about five feet, and paused. He stared at the water, got a little dizzy, and closed his

eyes tightly. He opened them again. Without looking over the side of the log, he backed off.

Joby and Corny laughed again. “There's a place a little farther down you can walk across, Rusty,” yelled Joby.

Rusty cracked a weak grin. “I'll take it!” he said.

He found the place. The creek was wider here. The water flowed in a lot of tiny rivers. There were spots of green,

slippery moss, but Rusty walked across without trouble.

Joby led them to another trap.

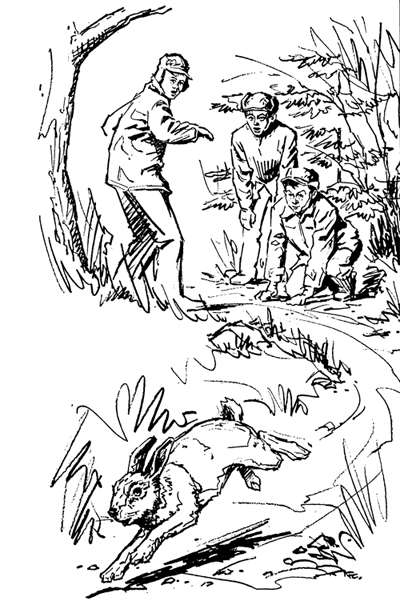

“Hey! Look at this!” he cried excitedly.

There sat a rabbit. At the sound of Joby's voice it hopped around a little. It didn't get anywhere. One of its hind feet was

caught in the trap.

The three boys stared at it in silence. Then they looked at each other.

Neither one of them moved for a long, long minute.

“F

IND

me a club,” said Joby.

Corny searched for one. He found a broken branch about two feet long. He handed it to Joby.

Joby took it. He looked at the club, and then at the rabbit. The rabbit was sitting still, its eyes big and wide.

Joby shook his head, and handed the club to Corny. “Here, you do it,” he said.

Corny took the club. He lifted it. The rabbit had not moved a bit.

Corny lowered the club. “Here. You do it, Rusty,” he said.

Rusty took the club. He looked at the

rabbit. The tip of its short tail looked like a ball of cotton.

“Not me. I can never do it,” said Rusty. He flung the club away.

Joby crouched beside the animal, opened the trap, and the rabbit hopped away on its three good legs.

“His leg will heal,” said Joby. There was kind of a joy in his voice, as if it made him happy to let the rabbit loose.

Rusty and Corny both smiled.

“Come on!” said Joby. “There's one more trap left!”

Joby led them to the shore of the creek. The trap was set near the water, with half of an apple on it for bait. The bait had

not lured any animal, though. The trap was still unsprung.

“Well, that's it,” said Joby. “Zero average. But I still think it's fun to trap!”

“Me, too!” said Rusty.

“You did catch a rabbit,” Corny reminded him.

“Yeah,” smiled Joby. “But rabbits are different. You can't kill them. They're like pets. You wouldn't kill your pet dog, would

you?”

“'Course not,” said Corny.

They retraced their steps through the woods, and went back home. Rusty knew he'd remember that trip for a long, long time.

He'd remember that log, too.

Later, from the window of his living room, Rusty saw Perry Webb, Corny, Ted Stone, and several other boys walking down the

road. Corny was carrying his basketball. As the boys passed in front of

Rusty's house, Corny looked at the house. He said something to Perry. Perry shook his head,

no

.

Corny wanted to ask me to go with them. But Perry doesn't want me to

. A lump rose in Rusty's throat.

A little while later Rusty got his own basketball and went outside. Dad had made a backboard above the garage door. Rusty

practiced shooting long shots. He tried hard not to think of Perry and the others.

He practiced until his legs got tired. Then he went inside to rest. Sometime later he saw the boys returning. He could hear

them chattering excitedly among themselves. Each was carrying a small bundle of blue and red under his arm.

Rusty knew what those bundles were.

They were suits — basketball suits. Alec Daws had passed them out.

Rusty turned, stretched out full length on the easy chair, and gazed at his legs. They looked the same as anybody else's.

But they were weak, slow.

Why did it have to be me?

“What's the matter, son?”

Rusty looked up. Dad was in the doorway, a tall man with dark hair and wide shoulders. His brown eyes were understanding.

“Nothing,” said Rusty.

“Nothing?” Dad chuckled. “I saw those boys walking up the street. They were carrying basketball suits, weren't they?”

Rusty shrugged. “I guess so,” he said.

“I think they were,” said Dad. “I heard the fathers talking about it in the store.

Alec Daws is going to buy suits and form a basketball team. I think it's a wonderful idea. Good for the boys. Why didn't you

go down and get your suit?”

Rusty looked at his father squarely. “Me? I can't make the team, Dad!”

“Oh?” Dad's brows lifted. “Who said you can't?”

Rusty put his elbow on the arm of the chair, sank his chin into the palm of his hand hopelessly. “I just know I can't,” he

said.

“You might be fooling yourself,” said Dad. “Alec is a pretty square shooter. He's not trying to form a team of champions.

He just wants a team. He wants to make it as good as he can, but he's not going to keep kids off who want to play. I've met

Alec. He's a nice, decent guy.”

“I know,” said Rusty. “I met him, too.”

He put on his jacket, got his basketball, and went outside again. Even when his legs got tired, he didn't quit. He grew awfully

hungry, too. But he still played.

Presently small flakes of snow fell. The flakes grew larger and began to stick to the ground. They fell on his cheeks, melting

instantly. Still Rusty played, working on corner shots. He was sinking them better as the minutes dragged on.

Patches of white formed on the ground. Rusty moved about much more slowly now. He didn't run after the ball when he shot.

He walked. He wanted to stay out as long as he could.

“Rusty, you've been out there for hours!” Mom's voice suddenly broke the silence around him. “Come into the house!”

“Okay, Mom!” he said.

He picked up his basketball, went in. He took off his coat and hat, dropped into a living room chair, and fell sound asleep.

D

URING

lunch hour on Monday, Perry Webb ran up behind Rusty in the hall.

“Hi, Rusty. Heard you're afraid of logs.”

Rusty whirled. “Logs? What logs?”

Perry laughed. “You know what I'm talking about. You went along with Joby and Corny last Saturday, didn't you? You came to

a log. They walked across it, but you didn't!”

Rusty blushed. “Oh, that,” he said.

Two other boys met him in the hall. They laughed and mentioned the log, too.

A knot formed in Rusty's stomach. He

walked faster, hoping to get away from the boys. They walked faster, too.

Rusty reached the end of the hall, turned right and started down the stairs. Suddenly, he stopped. Coming up were Joby and

Corny.

His eyes blurred as they bored into theirs.

“You — you told them!” he said angrily.

Joby's eyes widened. “Told them what?”

“You know what!” Rusty's voice rose sharply.

“Oh, forget it,” said Perry. “We were only kidding, Rusty. We didn't mean to hurt you.”

Rusty's gaze swung to Corny. Corny's face paled. “It was me, Rusty. I told them. But I didn't know they would —”

Rusty didn't wait for Corny to finish. He fled down the stairs as fast as he could.

He stumbled, gripped the banister tightly, caught himself, and went on. He entered the gym and sat down, his heart pounding

fiercely. He watched a scrub basketball game until the bell rang.

That afternoon, Rusty climbed off the bus in front of the Daws Grocery Store. He saw Alec carrying a garbage can around the

side of the building. Perry, Corny, and the others stopped and spoke to the tall coach of their new team. Rusty heard them

speak about their new uniforms, but he hurried past as if he didn't see Alec. Alec wasn't interested in him, anyway.

“Rusty! Wait a minute!”

Rusty turned.

Alec winked at him. “Be at the barn about six,” he said. “Can I count on you?”

Rusty looked at Perry, Corny, Joby, and

the others who were regular players at the barn. They looked back at him as if they didn't quite believe that Alec would invite

him

, Rusty.

“Okay,” he said. He turned, and continued home by himself.

That night, at six o'clock, Alec Daws gave Rusty his uniform. It had a number 6 on the jersey.

“I had it for you last Saturday,” Alec said. “I was sure you'd like to have one.”

The lump in Rusty's throat was as big as a baseball. “I — I sure did!” he whispered.

“Be here for practice with the rest of the boys every night this week,” went on Alec. “I arranged a game this Saturday with

the Benton Braves, a non-league team. Later on, there will be more. All

right. Put that suit aside for now. I want you to get on the B team.”

Rusty saw that members of the A team were Joby Main and Mark Andrews at the forward positions, Corny Moon and Bud Farris at

the guard positions, and Perry Webb at center.

For five minutes the A team showed strong power over the B team. Perry racked up three baskets himself, and Bud made one.

The B team didn't get any.

Alec exchanged some of the players to make the teams better balanced. This appealed to the boys. Rusty didn't enter into the

scrambles for the ball. He'd never have a chance, he thought. He played the corner, as Alec had told him to do.

But that evening he didn't sink a shot.

Just before the boys left for home, Alec

had them choose a name for their new team.