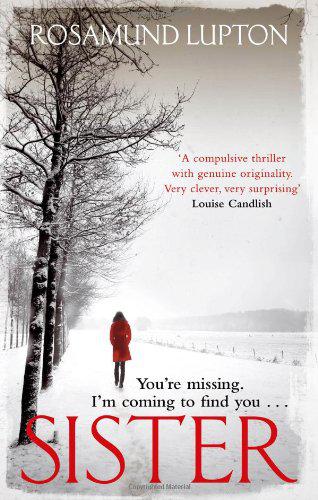

Sister: A Novel

Authors: Rosamund Lupton

Tags: #Murder, #Investigation, #Mystery & Detective, #Murder - Investigation, #Death, #Fiction, #Mystery Fiction, #Sisters, #Suspense Fiction, #Women Sleuths, #Sisters - Death, #Crime, #Suspense, #General

Table of Contents

Rosamund Lupton

has worked for many years as a scriptwriter. She lives with her husband and two sons in London. This is her first novel.

Published by Hachette Digital 2010

Copyright © Rosamund Lupton 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All characters and events in this publication, other than

those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious

and any resemblance to real persons,

living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 7481 1702 4

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

Hachette Digital

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette Livre UK Company

To my parents, Kit and Jane Orde-Powlett, for their life-long gift of encouragement.

And to Martin, my husband, with my love.

‘Where shall we see a better daughter or a kinder sister or a truer friend?’

Jane Austen, Emma

‘But flowers distill’d, though they with winter meet Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.’

Shakespeare, Sonnet 5

1

Sunday evening

Dearest Tess,

I’d do anything to be with you, right now, right this moment, so I could hold your hand, look at your face, listen to your voice. How can touching and seeing and hearing - all those sensory receptors and optic nerves and vibrating eardrums - be substituted by a letter? But we’ve managed to use words as go-betweens before, haven’t we? When I went off to boarding school and we had to replace games and laughter and low-voiced confidences for letters to each other. I can’t remember what I said in my first letter, just that I used a jigsaw, broken up, to avoid the prying eyes of my house-mistress. (I guessed correctly that her jigsaw-making inner child had left years ago.) But I remember word for word your seven-year-old reply to my fragmented home-sickness and that your writing was invisible until I shone a torch onto the paper. Ever since kindness has smelled of lemons. The journalists would like that little story, marking me out as a kind of lemon-juice detective even as a child and showing how close we have always been as sisters. They’re outside your flat now, actually, with their camera crews and sound technicians (faces sweaty, jackets grimy, cables trailing down the steps and getting tangled up in the railings). Yes, that was a little throwaway, but how else to tell you? I’m not sure what you’ll make of becoming a celebrity, of sorts, but suspect you’ll find it a little funny. Ha-ha funny and weird funny. I can only find it weird funny, but then I’ve never shared your sense of humour, have I?

‘But you’ve been gated, it’s serious,’ I said. ‘Next time you’ll be expelled for definite and Mum’s got enough on her plate.’

You’d been caught smuggling your rabbit into school. I was so very much the older sister.

‘But it’s a little funny too, isn’t it, Bee?’ you asked, your lips pursed trying not to let the laughter out, reminding me of a bottle of Lucozade with giggle bubbles rising, bound to escape with fizzing and popping on the surface.

Just thinking of your laughter gives me courage and I go to the window.

Outside, I recognise a reporter from a satellite news channel. I am used to seeing his face flattened into 2D on a plasma screen in the privacy of my New York apartment, but here he is large as life and in 3D flesh standing in Chepstow Road and looking straight back at me through your basement window. My finger itches for the off button on the remote; instead I pull the curtains.

But it’s worse now than when I could see them. Their lights glare through the curtains, their sounds pound against the windows and walls. Their presence feels like a weight that could bulldoze its way into your sitting room. No wonder the press are called the press, if this goes on much longer I could suffocate. Yes, OK, that was a little dramatic, you’d probably be out there offering them coffee. But as you know, I am easily annoyed and too precious about my personal space. I shall go into the kitchen and try to get on top of the situation.

It’s more peaceful in here, giving me the quiet to think. It’s funny what surprises me now; often it’s the smallest things. For instance, yesterday a paper had a story on how close we have always been as sisters and didn’t even mention the difference in our age. Maybe it doesn’t matter any more now that we’re grown up but as children it seemed so glaring. ‘Five years is a big gap . . . ?’ people would say who didn’t know, a slight rise at the end of their sentence to frame it as a question. And we’d both think of Leo and the gap he left, though maybe gaping void would be more accurate, but we didn’t ever say, did we?

The other side of the back door I can just hear a journalist on her mobile. She must be dictating to someone down the phone, my own name jumps out at me, ‘Arabella Beatrice Hemming’. Mum said no one has ever called me by my first name so I’ve always assumed that even as a baby they could tell I wasn’t an Arabella, a name with loops and flourishes in black-inked calligraphy; a name that contains within it girls called Bella or Bells or Belle - so many beautiful possibilities. No, from the start I was clearly a Beatrice, sensible and unembellished in Times New Roman, with no one hiding inside. Dad chose the name Arabella before I was born. The reality must have been a disappointment.

The journalist comes within earshot again, on a new call I think, apologising for working late. It takes me a moment before I realise that I, Arabella Beatrice Hemming, am the reason for it. My impulse is to go out and say sorry, but then you know me, always the first to hurry to the kitchen the moment Mum started her tom-tom anger signal by clattering pans. The journalist moves away. I can’t hear her words but I listen to her tone, appeasing, a little defensive, treading delicately. Her voice suddenly changes. She must be talking to her child. Her tone seeps through the door and windows, warming your flat.

Maybe I should be considerate and tell her to go home. Your case is subjudice so I’m not allowed to tell them anything till after the trial. But she, like the others, already knows this. They’re not trying to get facts about you but emotions. They want me to clench my hands together, giving them a close-up of white knuckles. They want to see a few tears escaping and gliding snail-like down my cheek leaving black mascara trails. So I stay inside.

The reporters and their entourage of technicians have all finally left, leaving a high tide mark of cigarette ash on the steps down to your flat, the butts stubbed out in your pots of daffodils. Tomorrow I’ll put out ashtrays. Actually, I misjudged some of them. Three apologised for intruding and a cameraman even gave me some chrysanthemums from the corner shop. I know you’ve never liked them.

‘But they’re school-uniform maroon or autumnal browns, even in spring,’ you said, smiling, teasing me for valuing a flower for its neatness and longevity.

‘Often they’re really bright colours,’ I said, not smiling.

‘Garish. Bred to be spotted over acres of concrete in garage forecourts.’

But these wilting examples are stems of unexpected thoughtfulness, a bunch of compassion as surprising as cowslips on the verge of a motorway.

The chrysanthemum cameraman told me that this evening the

News at 10

is running a ‘special’ on your story. I just phoned Mum to tell her. I think in a strange mum-like way she’s actually proud of how much attention you’re getting. And there’s going to be more. According to one of the sound technicians there’ll be foreign media here tomorrow. It’s funny, though - weird funny - that when I tried to tell people a few months ago, no one wanted to listen.

Monday afternoon

It seems that everyone wants to listen now - the press; the police; solicitors - pens scribble, heads crane forwards, tape recorders whirr. This afternoon I am giving my witness statement to a lawyer at the Criminal Prosecution Service in preparation for the trial in four months time. I’ve been told that my statement is

vitally important

to the prosecution case, as I am the only person to

know the whole story

.

Mr Wright, the CPS lawyer who is taking my statement, sits opposite me. I think he’s in his late thirties but maybe he is younger and his face has just been exposed to too many stories like mine. His expression is alert and he leans a fraction towards me, encouraging confidences. A good listener, I think, but what type of man?

‘If it’s OK with you,’ he says, ‘I’d like you to tell me everything, from the beginning, and let me sort out later what is relevant.’

I nod. ‘I’m not absolutely sure what the beginning is.’

‘Maybe when you first realised something was wrong?’

I notice he’s wearing a nice Italian linen shirt and an ugly printed polyester tie - the same person couldn’t have chosen both. One of them must have been a present. If the tie was a present he must be a nice man to wear it. I’m not sure if I’ve told you this, but my mind has a new habit of doodling when it doesn’t want to think about the matter in hand.

I look up at him and meet his eye.

‘It was the phone call from my mother saying she’d gone missing.’

When Mum phoned we were hosting a Sunday lunch party. The food, catered by our local deli, was very New York - stylish and impersonal; same said for our apartment, our furniture and our relationship - nothing home-made. The Big Apple with no core. You are startled by volte-face I know, but our conversation about my life in New York can wait.

We’d got back that morning from a ‘snowy romantic break’ in a Maine cabin, where we’d been celebrating my promotion to Account Director. Todd was enjoying regaling the lunch party with our big mistake:

‘It’s not as though we expected a Jacuzzi, but a hot shower wouldn’t hurt, and a landline would be helpful. It wasn’t even as if we could use our mobiles, our provider doesn’t have a mast out there.’

‘And this trip was spontaneous?’ asked Sarah incredulously.

As you know, Todd and I were never noted for our spontaneity. Sarah’s husband Mark glared across the table at her. ‘Darling.’

She met his gaze. ‘I hate “darling”. It’s code for “shut the fuck up”, isn’t it?’

You’d like Sarah. Maybe that’s why we’re friends, from the start she reminded me of you. She turned to Todd. ‘When was the last time you and Beatrice had a row?’ she asked.

‘Neither of us is into histrionics,’ Todd replied, self-righteously trying to puncture her conversation.

But Sarah’s not easily deflated. ‘So you can’t be bothered either.’

There followed an awkward silence, which I politely broke, ‘Coffee or herbal tea anyone?’

In the kitchen I put coffee beans into the grinder, the only cooking I was doing for the meal. Sarah followed me in, contrite. ‘Sorry, Beatrice.’

‘No problem.’ I was the perfect hostess, smiling, smoothing, grinding. ‘Does Mark take it black or white?’

‘White. We don’t laugh any more, either,’ she said, levering herself up onto the counter, swinging her legs. ‘And as for sex . . .’

I turned on the grinder, hoping the noise would silence her. She shouted above it, ‘What about you and Todd?’

‘We’re fine thanks,’ I replied, putting the ground beans into our seven-hundred-dollar espresso maker.

‘Still laughing and shagging?’ she asked.

I opened a case of 1930s coffee spoons, each one a differently coloured enamel, like melted sweets. ‘We bought these at an antiques fair last Sunday morning.’

‘You’re changing the subject, Beatrice.’

But you’ve picked up that I wasn’t; that on a Sunday morning, when other couples stay in bed and make love, Todd and I were out and about antique shopping. We were always better shopping partners than lovers. I thought that filling our apartment with things we’d chosen was creating a future together. I can hear you tease me that even a Clarice Cliff teapot isn’t a substitute for sex, but for me it felt a good deal more secure.

The phone rang. Sarah ignored it. ‘Sex and laughter. The heart and lungs of a relationship.’

‘I’d better get the phone.’

‘When do you think it’s time to turn off the life-support machine?’

‘I’d really better answer that.’

‘When should you disconnect the shared mortgage and bank account and mutual friends?’

I picked up the phone, glad of an excuse to interrupt this conversation. ‘Hello?’

‘Beatrice, it’s Mummy.’

You’d been missing for four days.

I don’t remember packing, but I remember Todd coming in as I closed the case. I turned to him. ‘What flight am I on?’

‘There’s nothing available till tomorrow.’

‘But I have to go now.’

You hadn’t shown up to work since the previous Sunday. The manageress had tried to ring you but only got your answerphone. She’d been round to your flat but you weren’t there. No one knew where you were. The police were now looking for you.

‘Can you drive me to the airport? I’ll take whatever they’ve got.’

‘I’ll phone a cab,’ he replied. He’d had two glasses of wine. I used to value his carefulness.

Of course I don’t tell Mr Wright any of this. I just tell him Mum phoned me on the 26th of January at 3.30 p.m. New York time and told me you’d gone missing. Like you, he’s interested in the big picture, not tiny details. Even as a child your paintings were large, spilling off the edge of the page, while I did my careful drawings using pencil and ruler and eraser. Later, you painted abstract canvasses, expressing large truths in bold splashes of vivid colour, while I was perfectly suited to my job in corporate design, matching every colour in the world to a pantone number. Lacking your ability with broad brushstrokes, I will tell you this story in accurate dots of detail. I’m hoping that like a pointillist painting the dots will form a picture and when it is completed we will understand what happened and why.

‘So until your mother phoned, you had no inkling of any problem?’ asks Mr Wright.

I feel the familiar, nauseating, wave of guilt. ‘No. Nothing I took any notice of.’