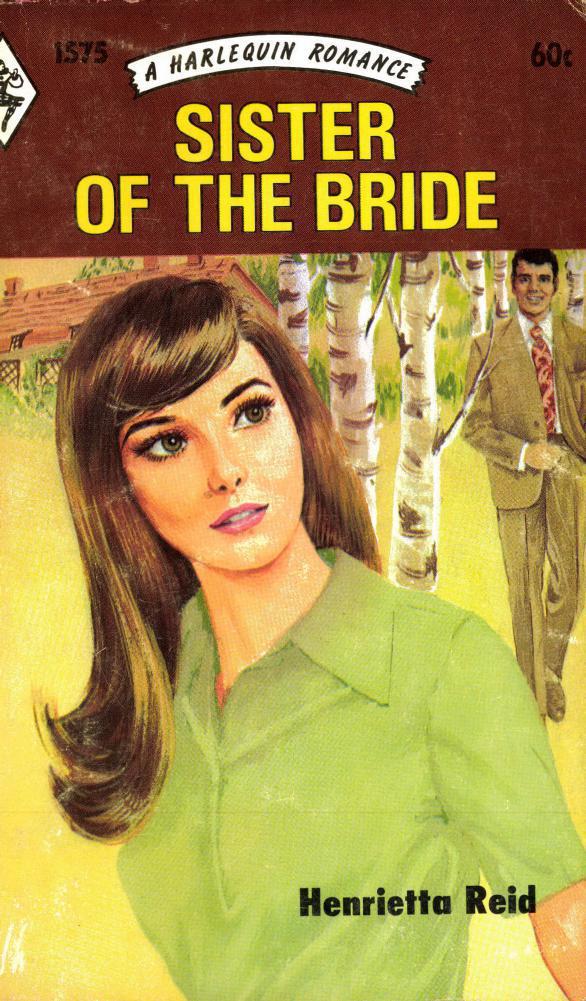

Sister of the Bride

Read Sister of the Bride Online

Authors: Henrietta Reid

SISTER OF THE BRIDE

H

enrietta Reid

Esther had always lived under the shadow - and under the thumb! - of her beautiful, ruthless older sister Averil.

Now Averil had talked her into looking after her little boy for a few

weeks, and instead of being bullied by Averil she soon managed to fall foul of the local lord of the manor, Vance Ashmore.

Would Esther never manage to assert herself?

CHAPTER ONE

I FELT my heart sink as I saw my mother lay down her cup with a little crash and peer frowningly at the morning paper. I knew then that she had seen that small notice in the ‘Forthcoming Marriages’ column. Not that I had really had any hope that she would overlook it! It was the part of the paper she always perused first.

‘So Olive Pemberton is to marry Ross Overton,’ she said sharply. ‘To think that at one time you could have had him, Esther, if you had only

e

xerted yourself!’

My heart sank as I realized she was beginning one of her tirades.

‘It

would

have been such a brilliant match too! Ross could have given you everything a girl could desire out of life. And he was so attentive to you at Averil’s wedding: everyone said it was obvious he was smitten. To think that if you had played your cards properly you could have spent your honeymoon at the Overtons’ villa in the south of France. It’s right on the Mediterranean. What on earth possessed you to fling him into Olive’s arms—and it

’

s not as if she were a beauty! After all, it shouldn’t have been difficult to be more attractive than Olive. I expect she’s crowing

over you too—’

I made a pretence of buttering a piece of toast. It wasn’t true that Olive had crowed, for she was much too devious to show her feelings so obviously. But when she had displayed her star sapphire engagement ring to the rest of us at the office I had felt in her manner a barely suppressed triumph. So you thought you’d hooked Ross Overton, she see

m

ed to say. Well, there’s many a slip—

It was true, of course, as Mother had said, that Ross had been attracted to me on Averil’s wedding day. Perhaps it had had something to do with the new confidence I had felt as I surveyed myself in the long dress of apricot silk organdie with a tiny petal cap of the same colour. Ross Overton had been groomsman, and I remembered how elated I had felt at the reception when he had fetched me a glass of champagne and from then on had completely monopolized me. Apart from being handsome in a rough-hewn sort of way, he was heir to the wealthy Overtons and an

e

xtremely important personage in local affairs.

The guests had cast amused and speculative glances in our direction. So the groomsman was interested in the bridesmaid, they seemed to say. A classic situation and the perfect ending to a day that had gone without a hitch from the moment that Averil, coolly beautiful in dreamy white, had walked assuredly down the aisle. Mother, of course, had cried. But then that was the privilege of the bride’s mother. Apart from that, Averil had always been her favourite, and though she had been disappointed, she had given in when Averil had insisted on marrying Clive Etherton who was only an accountant with the Ashmore shipping company. It had dashed Mother’s hopes that my sister, with her radiant beauty, would make a brilliant marriage, and although she insisted that Averil was ‘throwing herself away’ she realized only too well how stubborn and self-willed Averil could be when it came to leading her own life. We were not to know then that within a few years Clive would be killed on a business trip to the Middle East and that Averil would be left a widow with a young son.

Strangely enough Ross Overton, who had the reputation of preferring sleek and sophisticated women, began to cultivate me: he would call for me after work at the stockbrokers’ office where I was secretary to one of the partners and sweep me off in one of the enormous Overton limousines. Old Miss Palmer, who had been with the firm since she was a girl, would grow animated when his burly figure appeared in the doorway. He had that effect on all the girls in the office. That’s why I hadn’t noticed that with Olive Pemberton it was something more than admiration that made her eyes bright and her sallow skin glow when he appeared. Later I was to know how tenacious and cunning she had been in managing to draw herself to his attention. I never quite discovered what it was she said to Ross about me, but quite suddenly the car no longer rolled up to the office in the evenings and the phone calls and invitations ceased. Not that by this time I particularly cared! Once I had become used to the heady excitement of being singled out by the most eligible man in our small town I had gradually begun to realize that Ross, in spite of his broad shoulders and blunt good looks, was shallow and selfish and utterly spoiled. So it was almost with relief that I saw he had transferred his interest to Olive. At least it left me without the problem of explaining to Mother why I had no intention of considering him in the light of a future husband. Yet it had not been easy to ignore the covert pitying glances of sympathy the others had given me when Olive had sailed in one morning

flaunting her magnificent ring with all the confidence of a girl whose future is assured.

It had been enough to bear the

humiliating

badge of rejection without my mother continually harping on what she called my ‘disappointment’. ‘Olive is the third girl in your office to get married. In fact, you must be the only one of your group left single—am I correct?’

‘Except Miss Palmer,’ I said quie

tl

y.

Mother gave a short contemptuous laugh. ‘Why, Miss Palmer must be about a hundred: she’s been with the firm since it was established. Surely you’re not comparing yourself to her?’

‘No, of course not,’ I said wearily.

‘How will you like, as time goes on, to be gradually bracketed with old Miss Palmer? Really, Esther, sometimes I think you make yourself as drab and uninteresting as possible. I had hopes that you’d show more sense than Averil. Do you realize that unless you buck up and exert yourself to be attractive you’ll end up on the shelf? But there, I know there’s no use in talking to you: you seem determined to grow into a cantankerous old spinster, like Miss Palmer.’

‘But Miss Palmer isn’t cantankerous: she’s one of the kindest people I know. And anyway, I’d rather be a spinster than marry someone I had no respect for.’

‘Fine words,’ my mother said bitterly, ‘but in a few years from now you’ll be singing a different tune, believe me.’

Exasperated at what she took to be a further display of my uncooperativeness, she turned impatiently to a little pile of letters beside her place. She tore open an envelope bearing Averil’s flamboyant scrawl and was soon engrossed.

I fixed my eyes on a ray of sunlight that glittered and splintered off the glass marmalade dish. I mustn

’

t let Mother’s reproaches undermine my already wavering self-confidence, I told myself firmly. Yet it was impossible not to feel a familiar twinge of regret and vague longing. Through the open window I could see the clusters of pale wild daffodils that grew underneath the hedge, their heads nodding in the light exhilarating spring air. It was a time of youth and renewal, yet for me there were no golden promises. In spite of my championship of old Miss Palmer I felt a cold chill as I contemplated the future. How many future springs would pass and see me still the victim of Mother’s continual nagging? Would life quietly and inexorably slip away, leaving me nothing but vain regrets?

‘This is for you: Averil enclosed it in her letter.’ Without looking up, Mother passed me a folded sheet of paper.

I opened it curiously. It was not often Averil wrote to me. We had little in common and as children had quarrelled almost continually. Even then Averil had been a beauty; always the one to attract notice and admiration. In my own childish way I had resented the fact that she came first with my mother: I had withdrawn into a dream world of my own and, against Avail's gay and irrepressible character, had seemed sulky and bad-tempered. When she had grown up, too, it was Averil the boys had fluttered after, and as I was the younger sister I had become used to Avail’s triumphs and in fact had felt a sort of reflected glory in

running

errands for her and generally playing gooseberry as she flirted with one boy after another.

It was different, of course, when she met Clive and fell head-over-heels in love. After her marriage they had settled in London and we had seen very little of them, so I was surprised to see that the letter was headed ‘Cherry Cottage, Warefield.’ Warefield was a small market town, about fifty miles from, us, rural and sleepy. Not at all the type of place that would appeal to my sophisticated sister!

‘Dear Mouse,’ Averil began. This was the name she always called me when she was bent on wheedling me into agreeing with one of her schemes. ‘I expect the address surprises you, and I must say that it rather surprised me to find myself in one of those quaint ye olde worlde cottages, full of creaking beams and tiny rooms. In fact, Cherry Cottage is not my idea of “a most desirable residence.” However, as you know, Clive, poor darling, didn’t leave me particularly well off and when the head of Ashmore’s offered me the tenancy of the cottage in the grounds of their country home, I jumped at it. After all, beggars can’t be choosers. In the old days it belonged to the wheelwright who worked in the Ashmore stables—that is when they had carriages—and is situated in a nook of the grounds of Ashmore House, which is very big and Victorian and rather ghastly in an imposing sort of way. Altogether we’re rather feudal down here and I can barely restrain myself from bobbing a curtsey and addressing Vance Ashmore as Master. Actually it’s a title that would suit him rather, as he’s extremely grim and autocratic and altogether intriguing.

‘Anyway, Rodney simply loves it and spends his time chasing the animals and fighting with the local children. I can’t say I’m particularly enamoured of our new home. Give me the bright lights every time, but on the other hand it has certain compensations which I shall not enumerate at this stage. And now, dear

Mouse, I have a favour to ask. Quite out of the blue Sheila Richardson has asked me to accompany her to the West Indies where she’s joining her husband in Nassau. We would be going out in a cruise ship as Sheila simply has a thing about planes. It would be a terrific opportunity for me to get away from things for a bit and I’d simply love to take her up on the offer. But the

snag

is there’s no one here at Warefield I know well enough to take charge of Rodney and, as you know, he can be a bit of a handful at times. I was wondering if you could possibly come down here and take over until I return.

‘Couldn’t you ask that nice boss of yours if you could take your holidays now and let me join Sheila?

I’ll

be simply desolated if I miss this opportunity and, after all, it would be like a holiday for you. Cherry Cottage is the type of quaint old place I know you’d love and it’s frightfully rural here with everything in bud. So

d

o please say you’ll come, Mouse. There’s nothing like a shipboard flirtation for keeping a girl’s morale up, and in spirit I’m dancing on deck under the stars—’

I

put her letter down. Averil called me Mouse only when she was bent on getting her own way. It was a half derisive, half condescending name she had evolved for me when we had been children, and it expressed my position in relation to her so accurately that I had always hated it, although I had never given her the satisfaction of letting her know how much I resented it.

So Averil was, as usual, determined to get her own way! Did she imagine I could drop everything and rush off to Warefield, just because she wanted to go on a pleasure trip? I could imagine the expression on Miss Palmer’s face were I to announce that I was

leaving the office to take over the management of an extremely spoilt eight-year-old boy, as my sister had an overwhelming urge to dance under the stare.

I must have smiled wryly at the fancy, for Mother said pettishly, ‘Really, Esther, there’s nothing to grin about. I assume Averil has told you of this cruise she has in mind. She asks me quite casually if I’ll let you go off to take care of young Rodney. I must say it’s most thoughtless of her. She must know how much I depend on you. If you go, who is to stay here with me? I’d be simply terrified at night alone in this house. But then Averil has no consideration.’

It was not often Mother found' fault with her favourite and perhaps at that moment we came as near to seeing eye to eye as we ever did.

‘You’ll just have to w

ri

te to her and tell her how impossible the whole idea is: if she wants to go off gallivanting, let her get someone locally to take care of Rodney.’

‘

But she hasn

’

t been long enough there to know anyone she could trust him with,’ I pointed out. ‘It seems that it’s only recently that Vance Ashmore offered the tenancy of the cottage.’

Mother knitted her brows thoughtfully. ‘It’s only right that Vance Ashmore, as head of Clive’s firm, should do something for Averil. After all, if Clive hadn’t been sent out to the East just when there was trouble brewing Averil wouldn’t have been left a widow. And she was always the type of girl who needed the steadying influence of a husband. But then every girl should have a husband. I’ve no time for this career-girl business. A home and family is what every girl needs, and if you had any sense—’

‘Couldn’t Rodney come and stay with us while

Averil is away?’ I suggested quickly, in an effort to head Mother off her now familiar tirade.

Mother stopped in mid-sentence. ‘Rodney come to us?

’

she demanded, outraged. ‘You’re surely not suggesting that a child as undisciplined as he is should actually stay here? My poor nerves would never stand it. It was bad enough when he was younger and I went to stay with Averil in London. He did nothing but run about the house yelling at the top of his voice and openly defying his mother. “Averil,” I said, “if you don’t put your foot down you’ll live to regret not taking that child in hand.” But of course she laughed it off and said that she didn’t want him to grow up a namby-pamby. What he must be like by now, an

d with the open countryside to run

wild in, I dread to think. Oh no, it’s out of the question he should come here, so put it out of your head.

’

My mother drummed her fingers thoughtfully, then added, ‘Still it seems a pity that she can’t take up this opportunity: Averil is not the type of girl who should remain a widow, and I must say that I’d be happier if she found a good steady husband.’