Skywalker--Close Encounters on the Appalachian Trail (35 page)

Read Skywalker--Close Encounters on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: Bill Walker

“Our last three presidents went to Yale,” Stranger noted. “Did they skip the White Mountains hiking portion of their education?”

“That is a matter of great debate, of course,” she diplomatically responded.

The AMC (Appalachian Mountain Club) is the oldest mountaineering organization in the United States, established in the 1870s. It reportedly has a healthy six-figure budget just for search and rescue in these mountains. Its most notable accomplishment, though, is building the hut system in the White Mountains. These eight huts, built in some of the most remote places in the range, were an engineering feat of the highest magnitude, as well as a demonstration of raw manpower. In the summer they are usually full, despite prices in the eighty dollar range for a small, rectangular bunk and a modest meal.

English Bob and I struggled through relentless rocky climbs and descent to arrive at the Zealand Hut after ten miles. Our mileage was plummeting in the Whites, but that was budgeted in my schedule.

Doctor Death and a short, late-fiftyish, balding fellow named DA were among those there doing “work for stay.” It was a great deal, but only a few people got to do it at each hut. Some hikers chose to hike short distances to arrive at a hut in the early afternoon and reserve one of the “work for stay” spots. When I asked the hut manager he said, “Sorry, we’re full.”

Then he said, “We try to entertain our guests here. Can you think of any memorable lines you’ve heard about the Whites.” I looked at a bulletin board that read, “The weather in the Whites is like herpes, off and on.”

I walked out onto the porch, discouraged, and gave English Bob the news. Just then a tide of cold wind and rain ripped through the trees. “This is serious, dangerous weather,” Doctor Death said ominously,

DA looked out and said humbly, “I wonder if I’m ever going to make it out of the Whites.”

DA was a district attorney from Oklahoma, doing the second half of the AT this year. We hit it off probably because we were both humbled by the circumstances. He was going to hike down a side trail the next day to re-supply and insisted on giving me one of his Lipton dinner packages. Finally, the hut manager came out after all the guests had eaten and offered to let us sleep on the floor for eight dollars, after the guests had left the dining room. We were relieved.

The next night, after an ambitious fourteen-mile hike in schizophrenic weather, we arrived at the Mitzpah Hut. Again, we were too late, and the “work for stay” spots were filled. But, eager to get relief from the cold rain, I asked the hut manager, “Could we pay you to sleep on the floor?”

This particular hut manager didn’t exactly goose step, but you got the impression he could learn quickly. “The more you stay in contact with nature, the better,” he replied “There is a site for tents out back.” In fact, several years back, a couple hikers had frozen to death while camped out behind this hut.

“Have you seen the weather?” I asked, peeved.

“It will help you get ready for northern Maine in the fall.”

“Will you be tenting out tonight?” I asked testily.

“I’m the manager,” he replied flatly. Even deep in the mountains you can’t escape all human hierarchies.

After a frigid evening we climbed up Mount Pierce the next morning in very poor visibility, and once again violated treeline. In fact, the next fifteen miles on the AT are the longest stretch in the entire eastern United States above treeline. We were enveloped in clouds, wind, and rain. We strained to follow the cairns. “Is there anybody else on this planet?” English Bob joked. But no joking matter it would be if one got lost out in this.

Finally, the well-known Lake of the Clouds Hut came into view. Completed in 1915, it’s the most elevated and most popular hut in the Whites. I asked to do work for stay and they obliged.

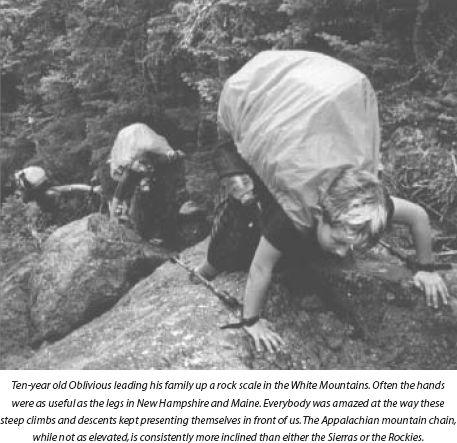

I was washing dishes when the Troll family arrived in late afternoon, anxiously asking to do work for stay. The hut manager looked dubious about what to do with them so I went over to make a plea. “The thing they do best is hunt bears,” I said. “They use little Oblivious’ head for bait.” Troll smirked, but the manager appeared confused. “Animals stay below treeline,” he responded. A few minutes later the Trolls were forming an assembly line with me at the dishwasher.

A diminutive, college-age girl came in bundled up from the cold, hauling a huge, bulging knapsack. “How much does that bloody thing weigh?” I asked.

“About sixty pounds.”

“Which is about sixty percent of your body weight,” I said incredulously.

“My record is one hundred ten pounds,” she said enthusiastically. “This is actually the easiest hut to deliver food to. They drive it up in a van to Mount Washington and we hike up to pick it up and carry it all downhill. At some of the other huts you have to carry it straight uphill.”

Hamburger had told me that in the Alps the food was taken up to the huts by horseback.

But the Whites were too rugged even for horse travel.

Any ascent on Mount Washington must be treated with great caution. Along with Mount Denali (McKinley), in Alaska, it is the most dangerous mountain in America. Its notoriously tempestuous climate is generated from lying between the warm Gulf Stream in the Atlantic and the frigid arctic air of Canada. Changes can be sudden and deadly.

The sign at the foot of Mount Washington read:

WARNING

THE AREA AHEAD HAS THE WORST WEATHER IN AMERICA.

MANY HAVE DIED FROM EXPOSURE EVEN IN THE SUMMER. TURN

BACK NOW IF THE WEATHER IS BAD

.

I

n 1951 John Keenan had graduated from high school in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and was “over the moon” about landing his first job on the Mount Washington survey crew. The first thing the other members of the survey crew told him at orientation on his very first morning was that clouds could close in very quickly. If this happened, he was told to simply stay where he was and they would come get him. At ten o’clock that first morning a sudden cloud engulfed them. The crew began calling for Keenan to come in, but he didn’t. Soon up to one hundred people were out searching for him. But, alas, he was never seen again.

On the day he disappeared a cold rain was being blown by a fifty-mile per hour wind on the Presidential Range. In such situations there is almost an irresistible impulse to walk downwind. It is less miserable on your face, requires less energy, and it feels as if nature is subtly urging you in that direction. Of course, in one sense, that is all rational. But it can be fatal.

Of course, there have been other notorious tragedies as well—the most famous probably being the teenage girl, Lizzie. Her family was caught in violent gales and freezing rain while three miles from the summit. An old stone motel called the Tip Top House used to sit at the summit, and the family attempted to force march up the mountain to reach it. But as they neared the summit they were at the point of exhaustion and could go on no longer in the blinding rain. Lizzie’s uncle prepared a crude windbreak to protect the family from the elements. But it wasn’t to be. “She was deadly calm,” her Uncle George reported, “uttered no complaint, expressed no fear, but passed silently away.” Tragically, the next morning the uncle awoke and the weather had cleared. They had camped out a mere “forty rods” from the hotel.

The common denominator in most of these tragedies is sudden weather change. Future Supreme Court Justice William Douglas wrote of his ascent on Mount Washington: “I felt comfortable enough. But suddenly the wind arrived like gunshot, and I was blue with cold. There were moments when I questioned whether I would be able to reach it. The experience taught me the awful threat that Mount Washington holds for incautious hikers.” Even the Native Americans were known to give Mount Washington a wide berth and view it warily. With precipitation 304 days per year, it’s almost impossible to predict what lies ahead.

But as we headed laboriously up the mountain, following the cairns, the wind gales blew away the clouds we had been wallowing in the previous five days. The sun came out. Right in front of us appeared the summit, the famous weather observatory, and the visitor’s center.

Mount Washington measures 6,288 feet and is the highest peak in New England. But despite that, and despite the throngs of tourists who pay to drive up the service road to see it, the summit is not especially impressive. That’s probably because unlike Mount Greylock and later Mount Katahdin, which dominate their local landscapes, Mount Washington is just a bit taller than the surrounding peaks in the Presidential Range.

Despite the lucky weather break a thermometer at the top showed the temperature was only thirty-nine degrees, sans wind chill, when we summitted. But we considered ourselves lucky, because the average temperature is twenty-seven degrees, and the mountain receives 175 inches of snow per year. But the more impressive statistic is the one recorded on April 12, 1934. On that day the Weather Observatory at Mount Washington dubbed, “the sturdiest building in America” recorded gusts on two different occasions of 231 miles per hour and several gusts of 229 miles per hour. It was the strongest wind ever recorded.

After a brief stop in the somewhat forgettable visitors’ center, the Trolls, Lemon Meringue, and I headed for the much tougher descent. Gusts of cold air rocked us in staccato fashion, even on this relatively good day. “The key is to get down as fast as possible to lower altitude,” Lemon Meringue said. “Jesus Christ, every bloody step is demanding,” I said exasperated. Indeed, the next several miles seemed to be just careful planting of feet from one boulder to another. A series of white crosses on the mountain commemorated the spot where various hikers had perished.

After a couple thousand feet of descent we stopped and took in the serene, azure sky and wide-ranging scenery. It was formidable, granite mountain summits as far as the eye could see. My mind flashed to Afghanistan, where the world’s most powerful army has been unable to catch the world’s most wanted terrorist. “You know,” I observed, “if you consider that Afghanistan has terrain similar to this, but over much larger areas, no wonder we can’t find Bin-Laden.”

“You have a point, Skywalker,” Lemon Meringue rejoined. “But this is what we’ve been waiting for and don’t ruin it by talking about politics.”

“I’ll take the pledge,” I lamely said.

“Instead, let’s talk about something interesting like sex,” the Triple-Crowner suggested. “Why are AT thru-hikers so shy and asexual compared to PCT and CDT hikers.”