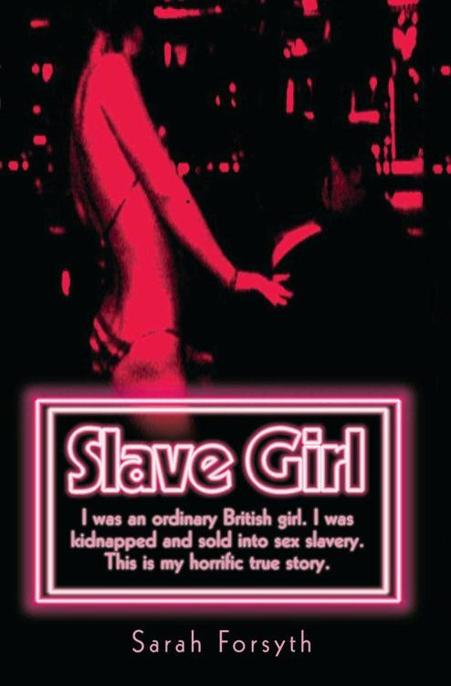

Slave Girl

Authors: Sarah Forsyth

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #True Crime, #General

I was an ordinary British girl. I was

kidnapped and sold into sex slavery.

This is my horrific true story.

Sarah Forsyth

with Tim Tate

O

n any given day, between 4,000 and 8,000 women are being forced to work – against their will – in the sex trade in Britain. They have been trafficked here, generally from Eastern Europe or Africa, and sold by international criminals into British brothels. Sex trafficking – transporting women and children across borders and forcing them into prostitution – is a 21st-century form of slavery: a violent and callous trade run by organised crime gangs throughout the world.

But the traffic is not all one-way: British women are sometimes tricked into the sex trade in just the same way as women in less-developed countries. They are trafficked to the Red Light Districts of Amsterdam, Frankfurt and other European capitals, and they endure the same miserable and drug-ridden existence as those sold into sexual slavery in Britain.

No British trafficked woman has ever come forward to describe her ordeal – until now.

The story of how Sarah Forsyth was tricked, trafficked and imprisoned in Amsterdam’s Red Light District is a dramatic and compelling insight into the closed world of international sex slavery. But the story of her life, abused first at home and then in care, and her long, difficult fight to survive is also the very human tale of a vulnerable young woman and her desperate journey to safety – a journey that is only just ending.

I met Sarah while I was making a documentary film for ITV in 2007. The film was a 90-minute special in which veteran investigative reporter Roger Cook re-visited and updated many of his most famous campaigns of the previous 20 years. One of those was a disturbing investigation in 1997 into international sex trafficking: one section within the programme briefly told Sarah’s story.

She had escaped from her ordeal a few years earlier and had helped to put her trafficker behind bars. But even so, she remained trapped in her own personal hell and, as the film depicted all too plainly, in 1997 Sarah was a complete wreck. She sat slumped in a chair, her make-up smeared and smudged, and her eyes all but invisible so far were they drawn back into her skull.

And her speech betrayed the reality of her life then: she slurred her words – viewers must have thought her either totally drunk or very heavily sedated. As it happened, it was the latter. Even so, what she had to say – what little she was able to enunciate – about her ordeal in the shop window of the sex trade was harrowing in the extreme. As best she could she outlined an existence – you couldn’t call it a life – in which she was forced to have sex with up to 17 men a day, seven days a week: but she also described truly inhuman cruelty.

After I’d finished work I used to go to bed and sleep in a locked room, guarded by a bull mastiff dog. And then I’d get a shower and get ready for work again. Sometimes after I’d finished work they used to play Russian roulette with me.

The interview took place just two years after her ordeal and the memories of what she had witnessed were still fresh in her mind. One of those memories was of witnessing the murder of another prostitute – apparently as part of an extreme pornographic video – and being warned by the man who controlled her that she too could face the same fate.

He went, ‘Watch it. If you don’t win the money,’ he said, ‘that’s what will happen to you.’ He said, ‘You are on a £50,000 contract to me, and,’ he said, ‘if you don’t make that money, I’ll put you in a movie like this, and,’ he says, ‘I can make a million off you.’

And at the end of the interview, tears streaming down her ravaged face, and with gulped pauses between her words caused by emotion almost too powerful to watch, Sarah Forsyth somehow summoned all her strength to spell out clearly and chillingly what her ordeal had done to her.

I went from being a nursery nurse to that. And now my life is ruined.

Everyone knows: Sarah was a prostitute.

Ten years later, I knew we had to find out what had happened to her. But Sarah wasn’t easy to track down. She had, it seemed, disappeared from the face of the earth and I feared that she must have succumbed to the fate that seemed almost inevitable back in 1997: the lonely miserable death of an incurable drug addict. But as the weeks wore on, tantalising snippets of news came through: glimpses of a woman on the streets of towns and cities across the north-east who might have been Sarah, or reports to police and social workers which suggested she had at least been alive – if not altogether healthy – within the previous two years.

And finally, after many more weeks of diligent enquiries by one of the production team, Sarah was tracked down to a flat less than a mile from her original neighbourhood. She looked immeasurably better than I had feared, and in some ways she had come a long way from the girl whose traumatised face and body I’d last seen on the

Cook Report

videotape ten years earlier. But appearances can be deceptive: Sarah was a long way from being either safe or better, and it would take many weeks of gentle, diligent work by every member of the team before we all felt she was strong enough to talk.

Throughout that spring and summer of 2007 I began to get to know Sarah Forsyth. Gradually, I became reassured that she had managed to put behind her the worst of what had been inflicted on her and was starting to take control of her life once again – though I remained uneasy about whether the future would be as trouble-free as she plainly hoped.

But what really shone out was Sarah’s determination that her story should be told – not for catharsis or as some kind of vindication, but because she knows the reality of sexual slavery today, knows just what the thousands of women trapped in British brothels are being put through and wants the world to listen.

And so, at Sarah’s request, this book is dedicated to them – and to the victims of sex trafficking whoever, wherever, they may be.

Tim Tate

October 2008

M

ore than anything it was the dogs.

There were two of them – bull mastiffs, sat on the other side of the door, day and night. I was locked in anyway, but if I even tried the handle the dogs would bark wildly and I knew that within seconds someone would be there to check on me. I was scared of the men who came running to the door of that shabby, dirty, miserable flat, but most of all I was terrified of the dogs. I knew what they could do –

would

do, given the chance – if the men let them at me.

Afterwards, that’s what no one seemed able to grasp. ‘Why didn’t you run away?’ they asked. ‘Surely you must have had

some

chance to escape?’

But the dogs were always there. Between them and the men – and the drugs they fed me day in, day out till I didn’t know which way was up and I’d reached that terrible place where I needed them as much as I hated them – there wasn’t a hope, really.

They knew that, of course. They’d worked hard to get me like that: to get me hooked on crack cocaine. That, and scaring me beyond belief by blowing a young girl’s brains out in front of my face.

I staggered through those days, weeks and months, each day the same: men and drugs, more drugs and more men. My life was ebbing away as slowly as the water in the dirty brown canal which oozed towards the North Sea. How many men paid their 150 guilders for a few minutes of rough and selfish relief? I couldn’t tell you: by the time I might have thought to keep count, I wouldn’t have been able to.

How many rocks of crack, how many lines of coke or joints of strong, calming marijuana did I consume? I couldn’t have tallied them up. Someone did, of course: nothing comes for free in Amsterdam, not in the Red Light District at any rate. And I paid the bill – the bill for the drugs that dulled my brain while I sold my body in the shabby neon-lit window by the canal – by selling myself again. A vicious cycle played out ten, fifteen times a day, seven days a week.

No, there wasn’t any escape from that hell. Not until that day when through the haze of my addiction and desperation I saw half a slim chance and somehow found the courage to snatch at it. Not until that day when my legs carried me away while my mind screamed with fear. Not until – for almost the first time in my life – someone came to my aid and stood beside me, not because they wanted something but out of common humanity.

That was the start of my journey out of hell: that first act of unselfish kindness. But if I’d known then how long the journey would be and how hard the road, would I have had the strength to start along it?

I honestly don’t know.

One

I

was born on Monday, 26 January 1976, at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Gateshead.

‘Monday’s child is fair of face,’ runs the old rhyme and I’ve been lucky enough to inherit my looks from my mother. She was – and still is – a petite woman with a good head of dark curly hair and wide brown eyes that sparkle with gentleness and with love. She’s in her fifties now but looks so young that she could be taken for an elder sister.

My father’s looks, though, are a very different story. Like I say, I’ve been lucky.

I was the second child in the family. My big brother was 18 months older than me, and my little sister was seven years younger. We all lived together in a little house in the sort of terraced streets they use today to film TV dramas set around the time of the First World War.

Gateshead back in 1976 was a scruffy, down-at-heel sort of town, clinging to the south bank of the Tyne and rather overshadowed by its big brother, Newcastle, on the other side of the river. When I was a child I looked up the history of the town in a book. People have lived here since Roman times and Gateshead is thought to mean ‘Head of the (Roman) road’.

But the town’s subsequent history isn’t particularly inspiring: a few semi-famous soccer stars were born here as well as the odd Victorian industrialist, and a woman who went on to become a Hollywood porn actress. Two famous people definitely passed through, though, and then passed on their impressions. In the 18th century Dr Johnson described it as ‘a dirty little back lane out of Newcastle’. Nearly 200 years later, JB Priestley pronounced that ‘no true civilisation could have produced such a town’, adding, for good measure, that it appeared to have been designed ‘by an enemy of the human race’.

I’ve lived in and around Gateshead most of my life. Nothing much has changed since and probably never will.

My dad was a bit of a local entrepreneur. He used to own two freezer shops and a restaurant, but I also have memories of him being a sales rep, travelling all over the north-east. But I’ve no idea what he sold and as it turned out I wasn’t ever going to ask too many questions about him. Mum was a housewife most of the time, looking after us bairns, but sometimes she worked night shifts at a local factory. Dad used to gather up us kids and pack us into the car in the middle of the night to go and pick her up.

Financially, we were pretty well off. Unlike a lot of folk in the town, Dad always made sure that we owned our own homes, never rented. We lived in nice neighbourhoods, always had plenty of food and I never went short of toys or clothes. In Gateshead that pretty much made us middle-class.

As children we were all really close – and absolutely devoted to Mum. I was particularly close to her – partly, I suppose, because I was her first daughter and there’s always something special in the relationship between a mother and her first little girl. I loved being so close to Mum – and loved, too, that I got to play Big Sister to both my siblings, even though my brother was actually older than me.