Small Lives

Pierre Michon

Small Lives

Translated from the French

by Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays

archipelago books

English Translation Copyright © Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays, 2008

Copyright © Pierre Michon, Editions Gallimard, 1984

First Archipelago Books Edition

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

without prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Michon, Pierre, 1945 â

[Vies miniscules. English]

Small lives / by Pierre Michon;

translated by Jody Gladding and Elizabeth Deshays.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-9357447-0-2

I. Gladding, Jody, 1955â II. Deshays, Elizabeth. III. Title.

PQ2673.I298V513 2008

843'.914âdc22Â Â Â Â Â Â 2007050889

Archipelago Books

232 Third St. #A111

Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.archipelagobooks.org

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

www.cbsd.com

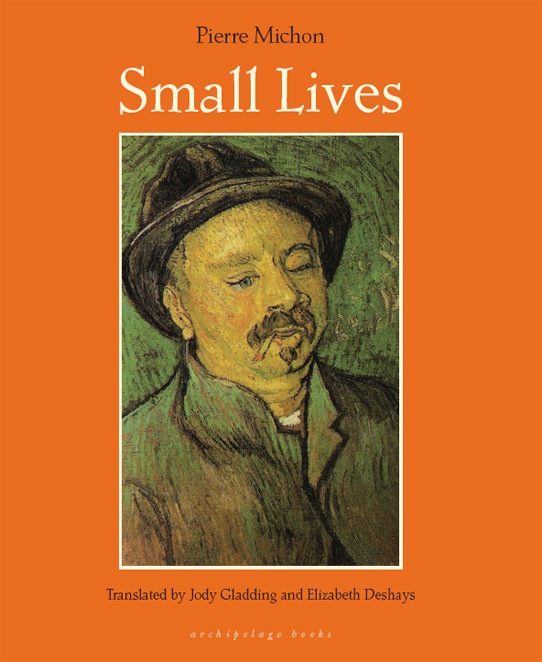

Cover art:

Portrait of a One-Eyed Man

by Vincent van Gogh, 1888

This publication was made possible with support from Lannan Foundation,

the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts,

a state agency, and the French Ministry of Culture.

to Andrée Gayaudon

Contents

The Lives of Eugène and Clara

The Lives of the Bakroot Brothers

The Life of the Little Dead Girl

Par malheur, il croit que les petites gens

sont plus réels que les autres.

A

NDRÃ

S

UARÃS

Small Lives

Let us explore a genesis for my pretensions.

Was one of my ancestors a fine captain, a young, insolent ensign, or fiercely taciturn slave trader? East of the Suez, some uncle gone back to Barbary in a cork helmet, wearing jodhpur boots and a bitter smile, a stereotype warmly endorsed by younger branches of the family, by renegade poets, all those dishonored ones full of honor, shadow, and memory, the black pearls of the family trees? Did I have some colonial or seafaring antecedent?

The province I am speaking of has no coasts, beaches, or reefs; no exalted Saint-Maloin or haughty Moco hears the call of the sea when the west winds, purged of salt and coming from far off, pour over the chestnut trees there. Nevertheless, two men familiar with those

chestnut trees no doubt took shelter there from the rain, perhaps they loved and certainly they dreamed there, then sought very different trees under which to work and suffer, not to assuage their dreams, perhaps to continue to love, or simply to die. One of these men I have heard about; the other I believe I remember.

Once in the summer of 1947, under the big chestnut tree in Les Cards, my mother carried me in her arms to the place where the village road can suddenly be seen emerging, hidden until that point by the wall of the pigsty, hazel trees, shadows. It was a beautiful day, my mother no doubt wearing a light dress, me babbling; on the road, preceded by his shadow, was a man unknown to my mother. He stopped, he looked, he was moved; my mother trembled a little; the inhabitual held its rest, suspended among the fresh notes of the day. Finally the man took a step forward and introduced himself. It was André Dufourneau.

Later, he said he thought he had recognized in me the baby girl who had been my mother, likewise an infant and still helpless, when he left. Thirty years, and the same tree that was the same, and the same child that was another.

Many years earlier, my grandmother's parents had asked the state to place an orphan with them to help on the farm, as was common practice then, at a time before such contorted, complacent mystification turned parenting into an extravagant, flattering and flattening mirror, in the guise of protecting the child. Then, it was enough if the child was fed, slept under a roof, and, from contact with his elders, learned the few gestures necessary for that survival from which he would make a life. As for the rest, it was assumed that youth in itself made up for

the lack of tenderness, the cold, hardships, and long labor, sweetened by buckwheat cakes, beautiful evenings, air as good as the bread.

André Dufourneau was sent to them. I like to think that he arrived one October or December evening, soaked from the rain or red-eared from the bitter frost. His feet struck that path that they would never again strike for the first time. He looked at the tree, the cowshed, the way the landscape stood out from the sky, the door. He looked at the new faces under the lamp, surprised or moved, smiling or indifferent. What he was thinking we will never know. He sat down and ate the soup. He stayed for ten years.

My grandmother, who got married in 1910, was still a girl. She grew attached to the child, whom she surely embraced with that gentle kindness of hers that I knew and with which she tempered the rough good nature of the men he accompanied to the fields. He had not gone and never did go to school. She taught him how to read and write. (I imagine a winter evening; the cupboard door creaks as a young peasant girl in a black dress opens it and takes down from the top shelf a small exercise book, “André's Book,” sits down beside the child who has washed his hands. Amidst the patois chatter, one voice distinguishes itself, strikes a higher note, strives for richer tones to shape the tongue around richer words. The child listens, repeats after her, timidly at first, then with confidence. He does not know yet that for those of his class and condition, born close to the earth and quick to fall back to it once again,

la Belle Langue

does not lead to grandeur, but to nostalgia and the desire for grandeur. He ceases to belong to the moment, the salt of hours becomes diluted, and in the agony of the past that is always beginning, the future rises and immediately begins to flow. The wind

beats the window with a bare wisteria branch. The child's frightened gaze wanders over the geography map.) He did not lack intelligence; no doubt people said that he “learned quickly.” Thus, based on these vague signs, and with the modest, lucid good sense of peasants in those days, who equated intellect with social rank, my ancestors developed a story to explain such incongruous qualities in a child of his condition, more in keeping with how they perceived reality: Dufourneau became the illegitimate son of a local squire, and everything was restored to order.

Who could say now if he was informed of this fantastical ancestry, born of the imperturbable social realism of the poor? It does not matter. If so, he thought of it with pride and resolved to win back, without ever having possessed, all he had been robbed of by his illegitimacy. If not, a vanity took hold in this peasant orphan, raised with vague respect perhaps, certainly with unusual consideration, that seemed to him all the more deserved, unaware as he was of its cause.

My grandmother got married. She was barely ten years older than him, and the adolescent he had already become may have suffered because of it. But my grandfather, I will say, was jovial, welcoming, a generous man and mediocre farmer. As for the child, I believe I heard my grandmother say, he was pleasant. No doubt the two young men liked one another, the cheerful victor of the moment with his blond moustache, and the other, the smooth-cheeked, silent one, secretly called, awaiting his hour; the eager one chosen by the woman, and the calmly flexed one chosen by a destiny greater than woman; the one who made jokes, and the one who was waiting for life to allow him to do so; man of earth and man of iron, without prejudice to their

respective strengths. I see them going off to hunt; their breath, dancing slightly in the air, is swallowed by the fog; their silhouettes fade into the edge of the woods. I hear them sharpen their scythes, standing in the spring dawn; then they walk and the grass is laid low, and the scent of it grows with the day, exacerbated by the sun. I know that they stop at noon. I know under which trees they eat and talk; I hear their voices but do not understand them.

Then a baby girl was born, the war came, my grandfather left. Four years passed, during which Dufourneau finished becoming a man. He took the little girl in his arms; he ran to alert Elise that the postman was on his way to the farm bringing one of Félix's painstaking, punctual letters. In the evening by lamplight he thought about the distant provinces where the din of battles razed villages to which he gave glorious names, where there were victors and vanquished, generals and soldiers, dead horses and impregnable cities. In 1918, Félix returned with some German weapons, a meerschaum pipe, a few wrinkles and a more extensive vocabulary than he had had at departure. Dufourneau barely had time to hear him out; he was called up for military service.

He saw a city; he saw the ankles of the officers' wives when they climbed into carriages; he heard young men whose moustaches lightly brushed the ears of beautiful creatures made of laughter and silk. It was the language he had learned from Elise, but it seemed like some other because its natives knew so many little paths, echoes, clever turns. He knew that he was a peasant. We will never learn how he suffered, in what circumstances he was made ridiculous, the name of the café where he got drunk.

He wanted to study, insofar as the constraints of the army permitted it, and it seems he achieved that goal, because he was a good boy, capable, said my grandmother. He held arithmetic and geography textbooks in his hands; he squeezed them into his pack that smelled of tobacco, the poor young man. He opened them and experienced the distress of one who does not understand, the rebelliousness that pushes on regardless, and, at the end of a dark alchemy, the pure diamond of pride when, for a breathless moment, understanding illuminates the ever opaque mind. Was it a person, a book, or, more poetically, a propaganda poster for the Marines that disclosed Africa to him? What bragging sub-prefect, what bad novel buried in the sands or lost in forests stretching over endless rivers, what magazine engraving of gleaming top hats passing triumphantly among gleaming faces, just as black and supernatural, made the dark continent sparkle with bright prospects? His calling was that country where the childish pacts you make with yourself could still, at that time, hope to find their dazzling revenge, provided you were willing to entrust yourself to the lofty, perfunctory god of “all or nothing.” It was there that this god played knucklebones, scattered the native ninepins, and disemboweled the forests under the enormous lead ball of a sun, staking and losing a hundred ambitious, fly-covered heads on the clay ramparts of the Saharan cities, pulling three white kings from his sleeve with a flourish. Then, pocketing his loaded ivory and ebony dice in their buffalo-skin bag, he disappeared into the savannahs, in madder-colored pants and white helmet, a thousand children lost in his wake.